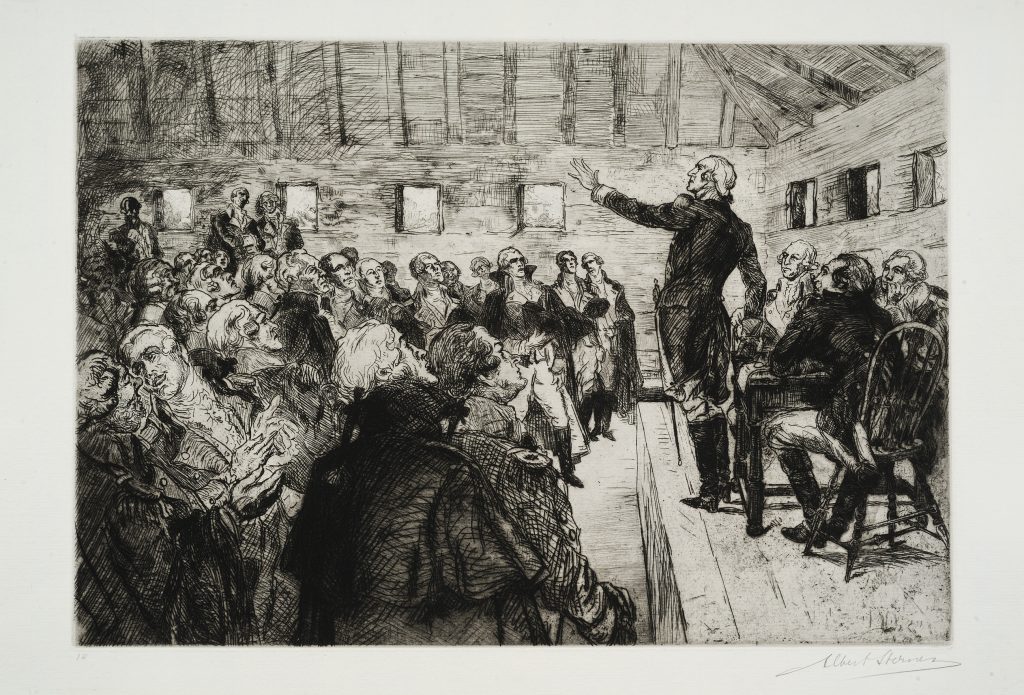

During their winter encampment two years after the storied American victory at Yorktown, General Washington’s officers found their patience with Congress wearing dangerously thin. By the ides of March, as they awaited a formal end to the War and for financial promises to the military to be honored, their frustration threatened to overtake their allegiance to America’s new civilian government. Their passions were heroically reined in by George Washington wielding two unexpected weapons—his unfailing integrity and his new reading glasses. This lesson explores the events at Newburgh and how George Washington’s vision for the United States and the ideals of republican sacrifice and civic virtue triumphed during a crisis that could have fundamentally altered the American experiment.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle and High School

Recommended Time Frame

Three fifty-minute sessions

Albert Sterner’s Washington Prevents a Military Dictatorship is from the portfolio “The Bicentennial Pageant of George Washington.” This illustration depicting the events at Newburgh, number fourteen in the series of twenty etchings, was issued in connection with the celebration of the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of George Washington in 1932 (The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati).

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will:

- understand why the period after the American victory at Yorktown before a formal declaration of peace is a critical time in America’s history;

- learn about the classical ideal of civic virtue and republican sacrifice embodied by Cincinnatus and revered by the Revolutionary generation; and

- appreciate how George Washington’s character and example of selfless service were integral to the foundation of the American republic.

Materials and Resources

(in order of appearance)

-

-

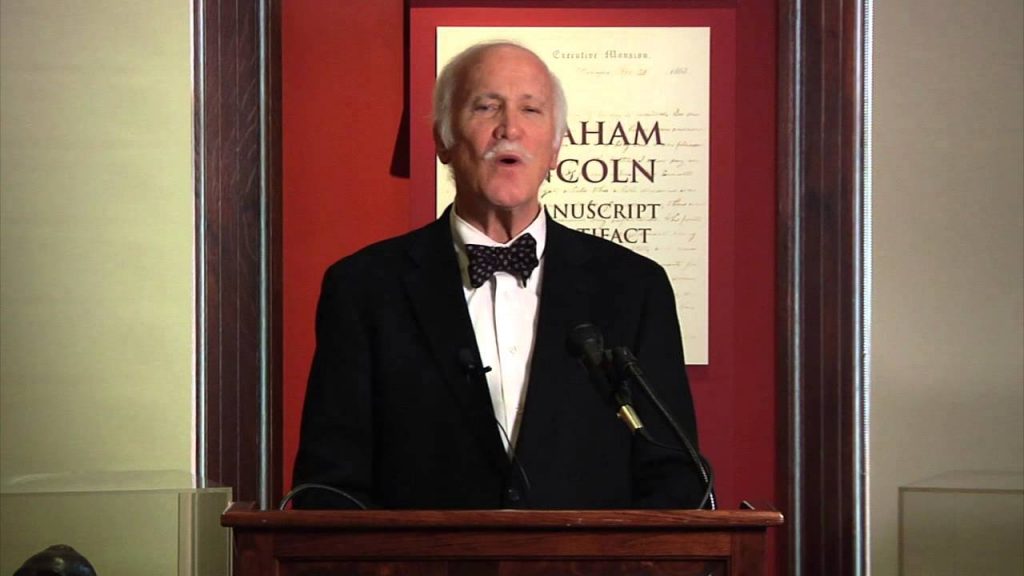

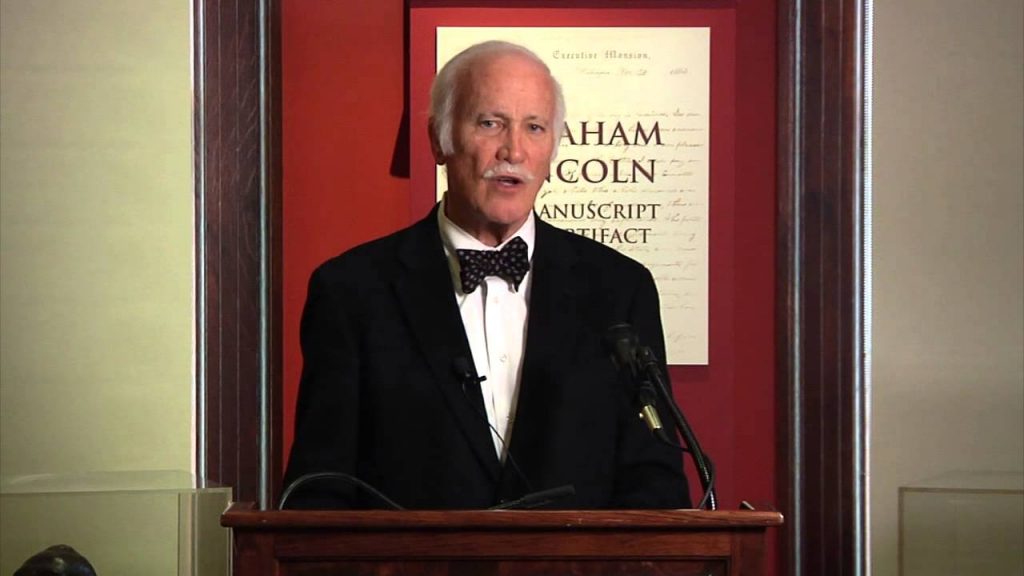

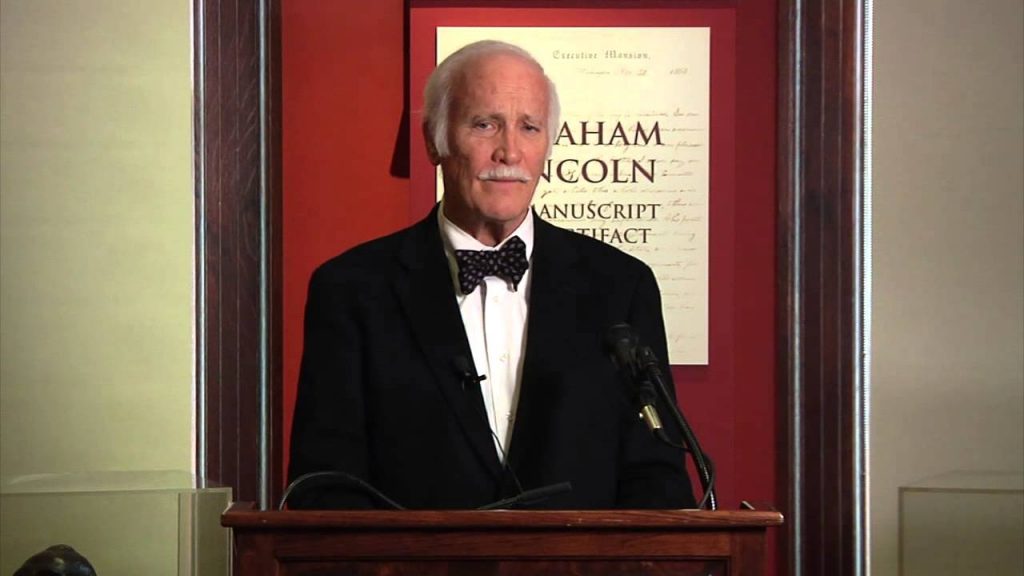

- William M. Fowler, Jr., The Critical Time After Yorktown, April 5, 2013, The American Revolution Institute’s America in Revolution Classroom Videos: “The Revolutionary War After Yorktown,” Part 1 of 8 (6:51), “The Newburgh Conspiracy: Revolt During the Revolution,” Part 5 of 8 (5:14), “George Washington’s Newburgh Address,” Part 6 of 8 (5:54) and “The Newburgh Address: Washington’s Sight and the Speech,” Part 7 of 8 (4:11)

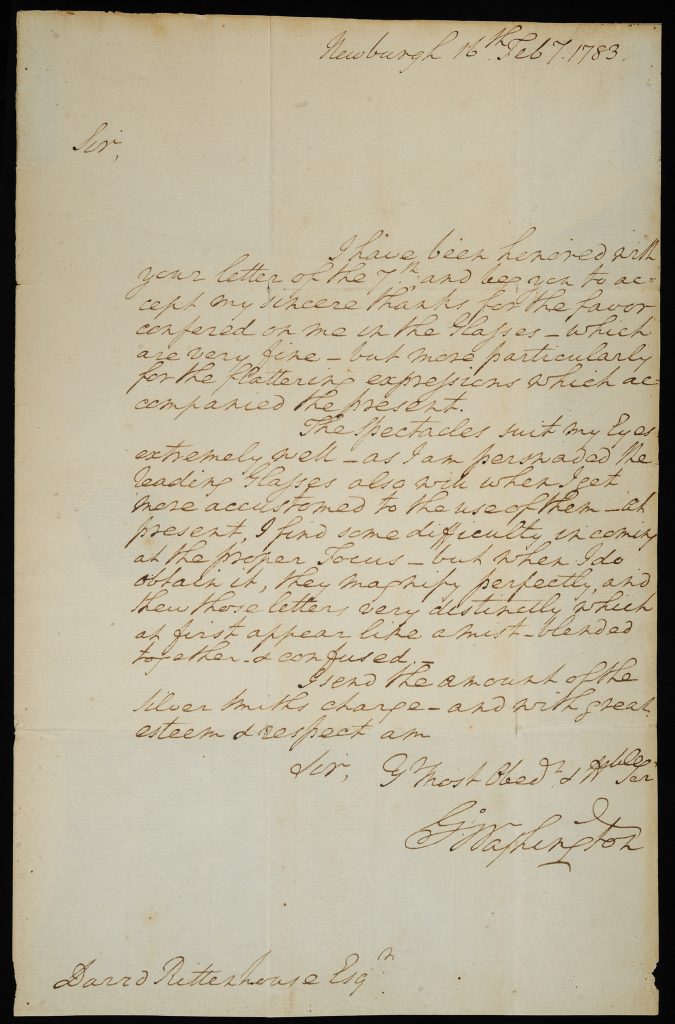

- George Washington to David Rittenhouse, February 16, 1783

- Saul Cornell, Civic Virtue in Early America, August 9, 2013, The American Revolution Institute’s America in Revolution Classroom Videos: “Civic Virtue Means Citizen Obligations,” Part 1 of 7 (6:01) and “Washington as the Modern Cincinnatus,” Part 3 of 7 (4:08)

- About [the Society of the Cincinnati] Name webpage

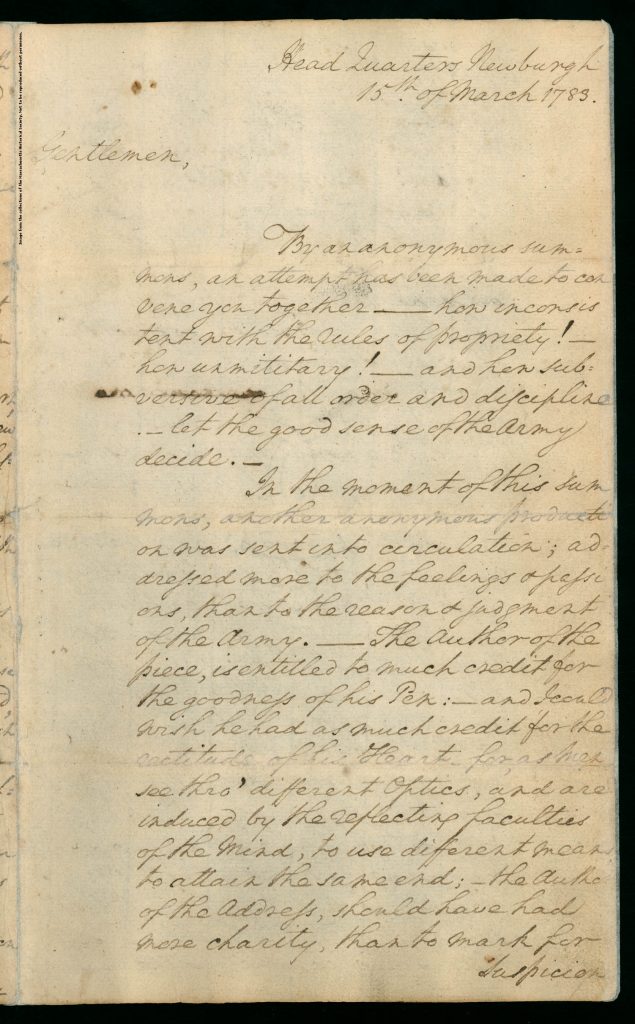

- George Washington, Newburgh Address, March 15, 1783

- Josiah Quincy [editor], The journals of Major Samuel Shaw : the first American consul at Canton : with a life of the author (Boston: Crosby and Nichols, 1847), pages 102-105

- George Washington, Address to Congress on Resigning his Commission, December 23, 1783

- United States Congress to George Washington, December 23, 1783

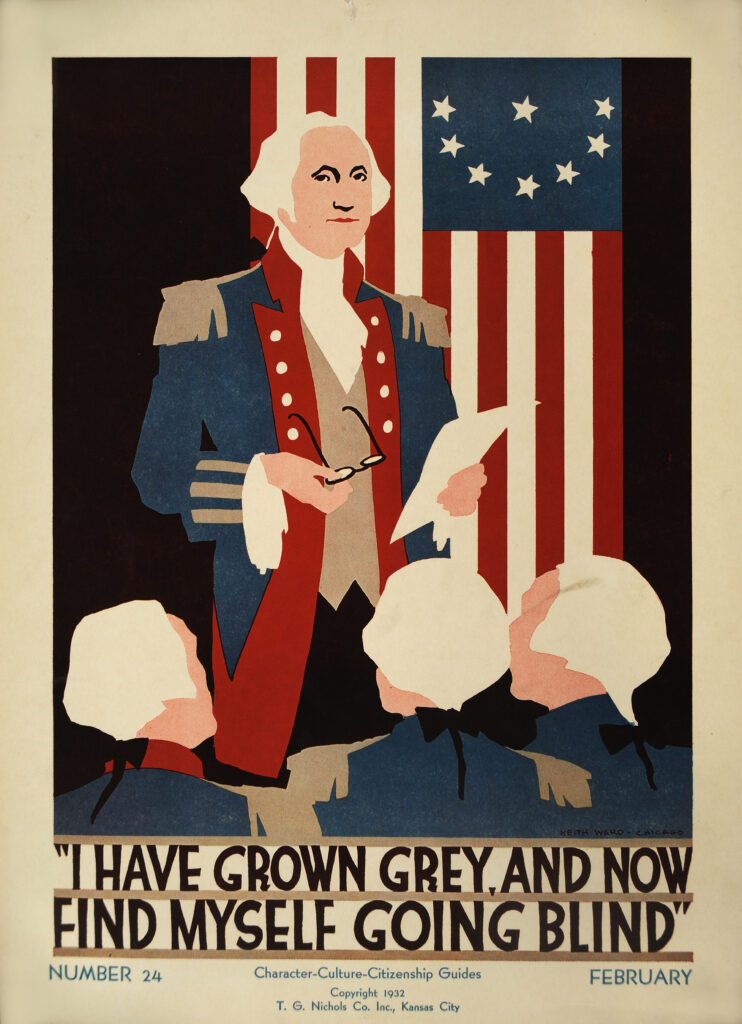

- Keith Ward. “I Have Grown Grey, and Now Find Myself Growing Blind” [poster]. T.G. Nichols Co. Inc.: Kansas City [Mo.], 1932.

-

Background Knowledge

Students should be familiar with the timeline of the American Revolution and understand that while the last major battle of the war was fought at Yorktown in 1781, peace was not formally achieved until 1783. Students should also know that George Washington served as commander in chief of the Continental Army from 1775 until his resignation following the declaration of peace in December 1783.

Sequence and Procedure

The surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781 did not end the American Revolution. The war continued for two more years before an official accord of peace was declared between the United States and the British Crown. During that period of uncertainty, the unpaid Continental Army entered a season of distress which nearly ended in rebellion. For a summary of this time, watch Dr. William Fowler describe the “The Revolutionary War After Yorktown.”

Ask students to read George Washington’s letter to David Rittenhouse in small groups or pairs and discuss what message Washington is conveying. Ask the class to share their thoughts about what they think is interesting or surprising about the content of this letter.

Ask students to watch “Civic Virtue Means Citizen Obligations” by Dr. Saul Cornell and record the examples of civic virtue and republican governments he shares. As a class, discuss these ideas—are they apparent in citizen conduct today?

Next, in small groups or pairs, have students read About [the Society of the Cincinnati] Name and record their answers to the question: Who was Cincinnatus, and what characteristics did he display that embodied civic virtue? Ask students to share their answers as a class, and to consider and discuss why Cincinnatus was revered by the Revolutionary generation.

Ask students to watch “Washington as the Modern Cincinnatus,” also by Dr. Cornell, and have them record the characteristics shared by Cincinnatus and George Washington. As a class, discuss this comparison.

Have students watch two short video segments by Dr. William Fowler, “The Newburgh Conspiracy: Revolt During the Revolution” and “George Washington’s Newburgh Address.”

Divide students into pairs or small groups and assign each a different section of Washington’s Newburgh Address to read and record the main ideas—prompt students by asking them to note what values, characteristics and actions Washington either praises or condemns. What is Washington’s vision for the United States?

David Rittenhouse had no formal early education yet went on to become one of the Revolutionary generation’s celebrated polymaths. Portrayed here in 1796 by Charles Willson Peale, he is surrounded by references to his scientific accomplishment—not the least of which was the construction of spectacles for General George Washington (National Portrait Gallery).

Ask students to return to the Washington letter to David Rittenhouse and note its date and the location from which it was sent in relation to the delivery of Washington’s Newburgh Address.

Have students watch Dr. Fowler’s “The Newburgh Address: Washington’s Sight and the Speech” (you may also ask students to read the short eyewitness account of Washington’s delivery of the address from Major Samuel Shaw’s journal). Ask students to describe, in writing, what other qualities of Washington’s character are demonstrated by his words and actions apart from the address itself—prompt students by asking them to record what feelings General Washington’s words and actions appear to evoke in his officers. How do Washington’s words and actions reflect his vision for the United States? Have students share their written observations.

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

Ask the class to brainstorm examples of of other Revolutionary men and women who displayed or wrote about the values of civic virtue and republican sacrifice like that demonstrated by George Washington at Newburgh in March 1783.

In small groups or pairs, ask students to choose one example to research further, collecting and documenting primary source evidence to illustrate and support their comparison. Encourage the groups to choose a research subject that is unique, and attempt to avoid duplication—examples of evidence could include the letters or journals of ordinary soldiers or prominent men and women as well as other manuscripts, accounts or publications. Have students share their research with the class.

Ask students to consider how George Washington might have followed up his February thank you to David Rittenhouse with another letter in late March reflecting on the experience of delivering his address at Newburgh. Have students draft a follow-up letter to David Rittenhouse “in the voice of” George Washington that includes his reflections about the events at Newburgh, discusses civic virtue and republican sacrifice, and (as an example) includes a reference to the Revolutionary man or woman the student researched. This letter should include some of the primary source evidence the student gathered about their research subject.

Extension

Ask students to read General George Washington’s Address to Congress on Resigning his Commission and Congress’s response to Washington. Instruct students to identify the descriptions of civic virtue, republican sacrifice and selfless service cited in the text of each—how does each reflect Washington’s vision for the United States? Whose words—Congress’s or Washington’s— refer more often to the virtues of republican service?

Revolutionary Achievements Category

Republic, Highest Ideals

Exploring the Revolution Category

The Revolutionary War, The Revolutionary Republic

"I Have Grown Grey, and Now Find Myself Growing Blind"

Keith Ward

T.G. Nichols Co. Inc.: Kansas City [Mo.], 1932The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

George Washington's reading glasses were used to great effect when Washington, in attempting to quell a brewing mutiny of officers at Newburgh, pulled them from his pocket and said "Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind."

George Washington to David Rittenhouse

February 16, 1783The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of George Miller Chester, Jr., in honor of his great-great-great-great grandfather, Col. John Chester, 2015

George Washington wrote a letter of thanks to noted American inventor and instrument maker David Rittenhouse for making him a set of spectacles (one for distance and one for reading). "The Spectacles suit my Eyes extremely well," Washington wrote, "as I am persuaded the Reading Glasses also will when I get more accustomed to the use of them - at present, I find some difficulty in coming at the proper Focus - but when I do obtain it, they magnify perfectly, and shew those letters very distinctly which at first appear like a mist blended together & confused." Three weeks later the reading glasses would be used to great effect when Washington, in attempting to quell a brewing mutiny of officers at Newburgh, pulled them from his pocket and said "Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind."

Newburgh Address

George Washington

March 15, 1783Massachusetts Historical Society

George Washington delivered his Newburgh Address to confront one of the greatest challenges to his influence with the officers and soldiers of the Continental Army. In the waning months of the Revolutionary War, after the victory at Yorktown on 19 October 1781, when the army was restlessly ensconced in winter quarters at Newburgh, New York, the officers, long unpaid and apprehensive about arrearages, retirement pay, and other well-deserved concessions denied them by Congress, teetered for a moment on the brink of open revolt against the country and government for which they had fought so hard and long. That the balance fell in favor of peace and order was due to General Washington's great influence with and true affection for his officers and soldiers alike. The address was brief, clear, and presented with great feeling; Washington exhorted his men to loyal and obedient, appealed to their patriotism, and offered his support for their cause. It was the most moving address he ever made, and afterwards the officers unanimously adopted a number of resolutions, including: "That the army continue to have an unshaken confidence in the justice of Congress and their Country . . . ; that His Excellency the Commander in Chief be requested to write to His Excellency the President of Congress, earnestly entreating the most speedy decision of that honorable body . . . ; that the officers of the American army view with abhorrence, and reject with disdain the infamous propositions contained in a late anonymous address ...."

The Critical Time After Yorktown, Part 1 of 8: The Revolutionary War After Yorktown

William M. Fowler, Jr.

April 5, 2013The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Many people assume that the Revolutionary War ended with the surrender of the British army at Yorktown in October 1781. In fact, the war continued for two more traumatic years. During that time, the Revolution came as close to being lost as any time in the preceding six years. When Congress failed to pay the army, rumors of mutiny roiled through the ranks, culminating in George Washington’s legendary address to his officers in Newburgh, New York, on March 15, 1783. Professor Fowler chronicles the events of the last two years of the war and discusses how Washington saved the republic.

Civic Virtue in Early America, Part 1 of 7: Civic Virtue Means Citizen Obligations

Saul Cornell

August 9, 2013The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Revolutionary Americans regarded civic virtue—a willingness to sacrifice personal interests for the good of the community—as vital to the preservation of republican institutions. The ideal of virtuous citizenship was rooted in classical antiquity and influenced American political thought and the art, architecture and literature that helped define the iconography of the new nation. Professor Cornell discusses the importance of civic virtue in early America and how it was expressed by American citizens, including the reverence for George Washington as the embodiment of civic virtue and a modern Cincinnatus.