“If any one of you, by observing the following rules, should save the life, or even limb of but one citizen, who has bravely exposed himself in defense of his country, I shall think myself richly rewarded for my labor.” Dr. John Jones, Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures (New York, 1775)

Our 2022 exhibition, Saving Soldiers, teaches its audience that the majority of the medical practitioners who served in the Continental Army—whose valiant work saving lives and easing the suffering of soldiers and sailors was essential to the achievement of American independence—learned their discipline through apprenticeship, with few having prior experience of war. This lesson plan asks students to analyze the primary source collection of rare books, manuscripts, portraits and artifacts featured in Saving Soldiers and write in the voice of one of these eighteenth-century healers, creating a field manual compiling best practices for treating soldiers for the review and endorsement of General George Washington and the Continental Army’s Hospital Department.

Suggested Grade Level

Elementary and Middle School

Recommended Time Frame

Three fifty-minute sessions

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will learn:

- what ailments and maladies befell soldiers during the Revolutionary War,

- how American military doctors serving in the Continental Army treated the sick and wounded, drawing from their experience before and during the war as well as available medical publications to forge a system of medical care based on the prevailing science of the time, and

- how the contributions of the war’s medical practitioners played as critical a role in the war’s outcome and the achievement of American independence.

Materials and Resources

(in order of appearance)

- Saving Soldiers: Medical Practice in the Revolutionary War catalog, The American Revolution Institute.

- “The Sentiments of An American Woman,” 1780. Esther De Berdt Reed. “The Sentiments of an American Woman.” 19th century-copy. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- George Washington to Ester De Berdt Reed, 14 July 1780.

- Ellen McCallister Clark, Benjamin Rush’s Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, April 15, 2022, The American Revolution Institute.

- Benjamin Rush. Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers Recommended for the Consideration of the Officers of the Army of the United States. Lancaster, Pa.: Printed by John Dunlap, 1778. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Robert Donkin. Military Collections and Remarks. New-York: Printed by H. Gaine, 1777. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- James Melvin. “James Melvin his book Anno Domini 1777.” Bound manuscript. [Page titled “Prisoner in Quebec” shown in facsimile.] The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Sir John Pringle. Observations on the Diseases of the Army, in Camp and Garrison. London: Printed for A. Millar [et al.], 1753. Dr. Samuel Tenny’s copy. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Gerard, Freiherr van Swieten. The Diseases Incident to Armies, with the Method of Cure. Philadelphia: Printed, and sold, by R. Bell, 1776. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- William Brown. Pharmacopoeia simpliciorum et efficaciorum in usum nosocomii militaris, ad exercitum foederatarum Americae civitatum pertinentis. Philadelphiae: Ex officina Styner & Cist, 1778. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Flame-stitch wallet owned by Ebenezer Crosby. 1774. Linen, wool, and silk. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Rear Admiral Schuyler N. Pyne, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of New Jersey, 1967.

- Lancet owned by Justus Storrs. Made by Benjamin Hanks, Mansfield, Conn., 1774. Brass and iron. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Justus Craft, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut, 1965.

- Scales and weights owned by Justus Storrs. 18th century. Oak, brass, metal, paper, and wool. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Justus Craft, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut, 1965.

- Mortar and pestle owned by William Chowning. 18th century. Ceramic and wood. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William J. Chewning, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, 1959.

- John Stephenson (1750-1807). American School. Late 18th-early 19th century. Oil on canvas. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Albert Walton, 1954.

- John Jones. Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures. New-York: Printed by John Holt, 1775. Dr. Henry Latimer’s copy. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Henry-François Le Dran. A Treatise, or Reflections, Drawn from Practice on Gun-shot Wounds. London: Printed for John Clarke, 1743. Dr. Charles McKnight’s copy. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Barnabas Binney. “A remarkable case of gun shot wound.” In Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, volume I (Boston: Printed by Adams and Nourse, 1785). The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Barnabas Binney (1751-1787). Artist unknown, possibly William Verstille, ca. 1779-1783. Watercolor on ivory. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Emily V. Binney, 1955.

- Surgical kit owned by Justus Storrs. Made by Evans & Co., London. 18th century. Leather, metal, tortoise shell, and velvet. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Justus Craft, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut, 1965.

- David Olyphant (1720-1805). By Samuel F. B. Morse, ca. 1818-1821. Oil on canvas. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Murray Olyphant, Jr., New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1985.

- William Burnet (1730-1791). American School, late 18th century. Oil on canvas. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Helen W. Ellsworth, 1994.

- Register of patients admitted to a Continental Army hospital. September 16, 1778-early January 1779. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- “Pay roll of a detachment of the part of the several Virg’a Regiments left in the hospital at Baltimore for one month.” Signed by Mordecai Gist and John Willis. June 14, 1777. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Peter St. Medard. Medical journal kept aboard the Continental frigate Deane and other vessels. Boston, 1777-1788. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- James Lind. A Treatise on the Scurvy. London: Printed for S. Crowder [et al.], 1772. Admiral Richard Digby’s copy. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Affidavit on behalf of James Warren, Jr., lieutenant of marines, in support of his petition for a state pension. Signed by Matthew Parke, Samuel Cooper, and James Warren [Sr.]. February 5, 1784. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Nathan Dorsey (1754-1806). By Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1775. Watercolor on ivory. On loan from the Corinne Dorsey Onnen Trust.

- Benjamin Rush, M.D. Engraved by Christian F. Gobrecht after a painting by Thomas Sully, 19th century. The Society of the Cincinnati.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Steuben. Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. Philadelphia: Printed by Styner and Cist, 1779. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- General Orders for the Army under the Command of Brigadier General M’Dougall…Concerning the Means of Preserving Health. Fishkill, N.Y.: Samuel Loudon, 1777. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Orderly book of the Sixth Pennsylvania Regiment. Kept by Capt. Jacob Bowers. January 1-April 27, 1779. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Thomas Shipley. A Receipt for a Cheap Soup for Six Persons, Published for the Use of the Private Soldiers and Their Families, Encamped on Cox-Heath, near Maidstone. Maidstone, Kent, England, 1778. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Hugh Williamson, M.D., LL.D. Engraved by Asher Brown Durand after a painting by John Trumbull, ca. 1812. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mary H. Pinckney, 2006.

- Clément Joseph Tissot. Gymnastique Médicinale et Chirurgicale. A Paris: Chez Bastien, Libraire, 1780. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- James McHenry to Margaret Spear Smith. July 1, 1781. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Perez Morton. An Oration Delivered at the King’s Chapel in Boston, April 8, 1776, on the Re-interment of … Joseph Warren, Esquire, President of the Late Congress of this Colony, and Major-General of the Massachusetts Forces, who Was Slain in the Battle of Bunker’s-Hill, June 17, 1775. Boston: Printed, and to be sold by J. Gill, 1776. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Enoch Edwards. “A List of Goods Belonging to Anthony Morris Dec’d.” January 11, 1777. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Edward Paine, Nathaniel West, and George Hubbard to Priscilla Birge, November 17, 1776. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Kezia Hobart. “Sacred to the memory of Mr. Daniel Hobert, who was slain at White-Plains, Oct. 29, 1776, AE 28 years.” Watercolor and ink on paper. 18th century. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- “Anchor’d in the haven of Rest.” Souvenir maker unknown. 20th century. Plaster. On loan from Glenn A. Hennessey, who represents Jabez Smith, Jr. in the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut.

- Sir John Pringle. Observations on the Diseases of the Army. First American edition with notes by Benjamin Rush. Philadelphia: Published by Edward Earle, 1810. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- David Ramsay. An Eulogium upon Benjamin Rush, M.D. Philadelphia; New York: Bradford and Inskeep, 1813. The Society of the Cincinnati, Library purchase, 2021.

- James Thacher. A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783. Boston: Published by Richard & Lord, 1823. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- James Tilton. Economical Observations on Military Hospitals and the Prevention and Cure of Diseases Incident to an Army. Wilmington, Del.: J. Wilson, 1813. The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection.

- Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia owned by James Tilton. Made by Jeremiah Andrews, ca. 1784-1791. Gold, enamel, silk, and metal. The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Elizabeth Tilton Beaudrias, 2021.

Background Knowledge

Students should be familiar with the colonial period in America and with the events of the American Revolution.

Sequence and Procedure

Part One: Share the Introduction to the Saving Soldiers Exhibition with Students

American military doctors who joined the cause for independence faced formidable odds. Of the 1,400 medical practitioners who served in the Continental Army, only about ten percent had formal medical degrees. The majority of the rest had learned their practice through an apprenticeship with an established physician. Most were young men at the beginning of their careers. Few had prior experience of war. Their civilian practices had not prepared them for the grim realities of warfare in eighteenth-century America, where far more soldiers under their care would die from disease and infection than would be killed on the battlefield.

Undaunted by these challenges, the healers played as critical a role in the war’s outcome as that of the warriors on the front lines. The field of military medicine was in its infancy at the time of the American Revolution. A generation earlier, Sir John Pringle had transformed medical care in the British army by emphasizing the need for order, cleanliness, sanitation and ventilation in military hospitals. Published a century before the discovery of microbes and antibiotics, Pringle’s Observations on Diseases of the Army was a pioneering work in the prevention of contagion and cross-contamination in treating the sick and wounded. Working under constrained and often brutal conditions—and with a perpetual shortage of medicines, supplies and personnel—American military doctors drew from Pringle and other writers to forge a system of medical care for the army based in the prevailing science of the time.

Each regiment of the army was staffed with a surgeon and surgeon’s mates who provided battlefield triage and critical care. The Hospital Department, created by Congress in July 1775, oversaw a more extensive staff of directors, physicians, purveyors and apothecaries who were responsible for managing and supplying the network of hospitals established across the states. With no clear chain of command between the department and the regiments, the delivery of adequate care to the troops was beset with administrative and logistical problems. Despite these obstacles, the medical practitioners kept their focus on their patients, working tirelessly to improve their condition and ease their suffering. In recognition of their service, Congress granted the army’s doctors the same rank and benefits as officers of the line.

After the war, most veteran military doctors returned to civilian practice. Several became leaders in their field, building upon the knowledge gained from their wartime experiences to promote reforms and advancements that would shape American medical practice for the next generation.

Part Two: Explore the Saving Soldiers Exhibition Galleries as a Class

Divide students into groups, assigning each group one or two different subtopic(s) from the exhibition:

-

-

-

-

- The Scourge of Smallpox

- Fighting Disease

- Treating Wounds and Fractures

- The Hospital Department

- Shipboard Medicine

- An Ounce of Prevention

- Diet, Exercise & a Clean Shirt

- Rituals of Death

- After the War

-

-

-

Each student group should read the corresponding subtopic gallery pages of the digital Saving Soldiers exhibition catalog, exploring and analyzing the primary sources cited (highlighted in the gallery below) and preparing a summary of their respective subtopic(s) to share with the class. The groups should introduce one or more of the key primary source items featured in their respective subtopic as part of their presentation to the class.

After all of the groups have reported their investigation summaries to the class, individual students should choose at least two subtopics to investigate on their own.

Part Three: Individual Student Research of a Subtopic

Direct students to research their subtopics further, finding evidence from the exhibition’s resources as well as supporting primary sources from other archives. No fewer than three rich primary sources should be secured by each student. For example, the letters exchanged between George Washington and Pennsylvania’s first lady Ester De Berdt Reed in July 1780—with Washington noting:

“A Shirt extraordinary to the Soldier will be of more service, and do more to preserve his health than any other thing that could be procured him”

or De Berdt Reed’s 1780 broadside “The Sentiments of an American Woman,” which proclaims:

“IDEAS, relative to the manner of forwarding to the American Soldiers, the Presents of the American Women. All Women and Girls will be received without exception, to present their patriotic offering; and, as it is absolutely voluntary, every one will regulate it according to her ability, and her disposition… the wants of our army do not permit the slowness of an ordinary path … The shilling offered by the Widow or the young girl, will be received as well as the most considerable sums presented by the Women who have the happiness to join to their patriotism, greater means to be useful.”

would serve as rich material for a student searching for resources on the Diet, Exercise & and Clean Shirt subtopic.

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

As a class, watch the video featuring Library Director Ellen McCallister Clark discussing Benjamin Rush’s Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, then explore an excerpt of Dr. Rush’s 1778 publication.

Direct students to write in the voice of Dr. Benjamin Rush, or another eighteenth century persona delivering medical care during the Revolutionary War, drafting recommendations for a field manual compiling best practices for treating soldiers on the subtopic they researched for the review and endorsement of General George Washington and the Continental Army’s Hospital Department. Students should support their work with evidence from primary sources and be prepared to share their work with the class. Teams of students who researched different subtopics could combine their work into a volume that includes all nine subtopics covered in the Saving Soldiers exhibition.

Extension

Invite students to investigate how eighteenth-century maladies and ailments are treated by medical professionals in the twenty-first century, what maladies and ailments confront today’s military medical providers, and what challenges are common to both eras.

Revolutionary Achievements Category

Independence

Exploring the Revolution Category

The Revolutionary War

Military Collections and Remarks

Robert Donkin

New-York: Printed by H. Gaine, 1777The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Throughout the war Americans harbored fears that the enemy was deliberately causing the spread of smallpox through the military and civilian population. Although it is difficult to prove specific cases of such biological warfare, there is fascinating evidence in this book by a British military officer, published in New York in 1777. In his chapter on “Bows,” Robert Donkin added a footnote: “Dip arrows in matter of small pox, and twang them at the American rebels, in order to inoculate them; this would sooner disband these stubborn, ignorant, enthusiastic savages, than any other compulsive measures. Such is their dread and fear of that disorder!” The audaciousness of Donkin’s suggestion did not go unnoticed, and the passage has been excised in nearly every known copy of his book.

The Diseases Incident to Armies, with the Method of Cure

Gerard, Freiherr van Swieten

Philadelphia: Printed and sold, by R. Bell, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

As the war began, American publishers sought out medical texts to meet the needs of the new army’s medical corps. This translation of the work of a prominent Dutch military physician was published in Philadelphia in 1776. The manual also included excerpts from the works of two British authors—John Ranby on the nature and treatment of gunshot wounds and William Northcote on the prevention of scurvy at sea.

Lancet owned by Justus Storrs

Made by Benjamin Hanks, Mansfield, Conn.

1774The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Justus Craft, Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut, 1965

Military physicians used lancets to draw out blood, score the skin for inoculation, and drain infections. This brass and iron example, inscribed with the name of its maker, Benjamin Hanks, belonged to Justus Storrs, a surgeon’s mate in the Connecticut Continental Line.

Pharmacopoeia simpliciorum et efficaciorum

William Brown

Philadelphiae: Ex officina Styner & Cist, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

William Brown, physician general of the Middle Department of the Continental Army, compiled this handbook of formulas for medicinal preparations while stationed at Lititz, Pennsylvania, in 1778. Known as the “Lititz Pharmacopoeia,” it set the standard for the military hospitals across the states. Acknowledging the chronic shortages of medicines, the author emphasized “such formulae as it is always in our power to obtain.”

Mortar and pestle owned by William Chowning

18th centuryThe Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William J. Chewning, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, 1959

This ceramic and wood mortar and pestle used in the preparation of medicines belonged to William Chowning, a surgeon’s mate in the Virginia State Navy.

Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures

John Jones

New-York: Printed by John Holt, 1775The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Dr. John Jones, a professor of surgery at King’s College in New York, was a veteran of the French and Indian War. Recognizing the inexperience of the new recruits to the medical corps, he published this manual “for the Use of young Military Surgeons in North-America” in New York in 1775. A second expanded edition, which included advice for naval surgeons, was published in Philadelphia the following year. This copy belonged to Dr. Henry Latimer, who directed the Continental Army’s “Flying Hospital,” a mobile surgical unit.

A Treatise, or Reflections, Drawn from Practice on Gun-shot Wounds

Henry-François Le Dran

London: Printed for John Clarke, 1743The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Early in his career, Dr. John Jones studied in Paris under Henry-François Le Dran, one of France’s leading military surgeons. Le Dran was a proponent of the Petit tourniquet as standard equipment for treating massive wounds and amputation. This English translation of Le Dran’s Traité ou Reflexions Tirées de la Pratique sur les Playes d'Armes à Feu bears the signature of Charles McKnight, who served as surgeon-general of hospitals in the Middle Department.

Barnabas Binney (1751-1787)

Artist unknown, possibly William Verstille

ca. 1779-1783The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Emily V. Binney, 1955

Barnabas Binney left his native Boston in 1774 to study medicine at the College of Philadelphia. In May 1776, shortly after earning his degree, he was commissioned a surgeon in the Hospital Department of the Continental Army. Dr. Binney spent more than seven years treating sick and wounded American soldiers. This watercolor portrait miniature painted during the war—possibly for Binney’s wife, Mary—depicts him in the uniform worn by Continental Army surgeons.

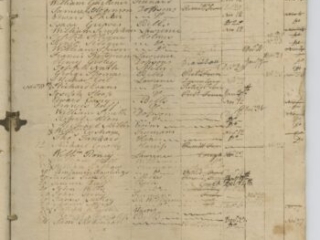

Register of patients admitted to a Continental Army hospital

September 16, 1778-early January 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Continental Army physicians relied on registers like this to account for and monitor patients under their care. This register lists patients according to their individual regiments and conveys important information pertaining to soldiers’ illnesses or injuries, with the malady crossed off when the patient was discharged. The inclusion of a column for “Deserted” along with “Fit for Duty” or “Died” is a telling indicator of the connection between health and morale within the army.

David Olyphant (1720-1805)

By Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872)

ca. 1818-1821The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Murray Olyphant, Jr., New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 1985

A graduate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, David Olyphant came to America following the Battle of Culloden (1746) and settled in South Carolina. From the early years of the Revolutionary War, he directed a general hospital in the Charleston area. He was appointed director general of hospitals in South Carolina in May 1781, and shortly thereafter he and his hospital staff were taken prisoner by the British during the Siege of Charleston. Following his release, Olyphant administered a hospital for American prisoners still held in Charleston. After the war, he moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where he continued to practice medicine. Dr. Olyphant’s son, David Washington Cincinnatus Olyphant, commissioned this posthumous oil portrait from American artist and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse.

Nathan Dorsey (1754-1806)

By Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827)

ca. 1775On loan from the Corinne Dorsey Onnen Trust

Nathan Dorsey served as a naval surgeon from 1776 until the end of the war. After his ship Raleigh endured several hours of cannon fire in 1778, he and fellow surgeons performed hours of amputations and wound dressing in the cramped, dark quarters. Later, as a prisoner on HMS Jersey, Dr. Dorsey tended to his fellow captives and was allowed to travel by boat to the hospital ship and to New York for medicine. Dr. Dorsey was the last surgeon to tend to a mortally wounded man in the war. This watercolor portrait miniature by Charles Willson Peale depicts Dr. Dorsey at about age twenty-one, shortly before he entered service in the Continental Navy.

Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers: Recommended to the Consideration of the Officers of the Army of the United States

Benjamin Rush

Lancaster, Pa.: Printed by John Dunlap, 1778The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Benjamin Rush’s essay emphasizing the importance of diet, dress, and camp hygiene to the maintenance of soldiers’ health was first published in the Pennsylvania Packet in September 1777. At the urging of Gen. Nathanael Greene, it was republished the following year in pamphlet form by John Dunlap, who had followed Congress to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, during the British occupation of Philadelphia. The Board of War ordered four thousand copies to be distributed to the officers of the army.

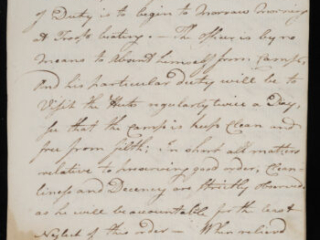

Orderly book of the Sixth Pennsylvania Regiment

Kept by Capt. Jacob Bowers

January 1-April 27, 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This regimental order of January 13, 1779, directs the appointment of a subaltern officer, whose “particular duty will be to visit the Huts regularly twice a Day, see that the Camp is kept Clean and free from filth; in short all matter relative to preserving good order, Cleanliness and decency are strictly observed, as he will be accountable for the least Neglect of this order.”

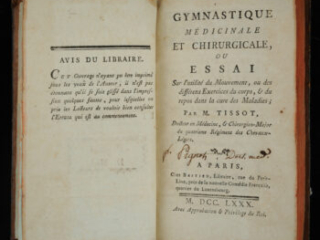

Gymnastique Médicinale et Chirurgicale

Clément Joseph Tissot

A Paris: Chez Bastien, Libraire, 1780The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

French military physician Clément Joseph Tissot pioneered the field of therapeutic exercise in the treatment of disease. His treatise on the subject, published in France in 1780, prescribed specific exercises for certain conditions and illnesses, the duration and intensity of which were to be adapted to the age and temperament of the patient. He warned of the dangers of too much bedrest, even in the treatment of such debilitating diseases as smallpox. He also discussed in detail the benefits of a great variety of sports to the maintenance of good health.

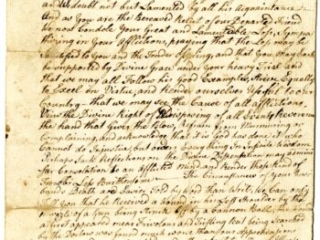

Edward Paine, Nathaniel West, and George Hubbard to Priscilla Birge

November 17, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This letter from Capt. Jonathan Birge’s fellow officers to his wife, Priscilla, informs her of his death. Jonathan Birge, a Connecticut captain during the New York Campaign, was wounded in his left shoulder on October 28, 1776, “by a muzzle of a gun being struck off by a cannon ball” during the Battle of White Plains. He died from his wounds on November 10 after the doctor “found the wound much worse than our apprehensions.” Captain Birge was forty-two years old and left behind Priscilla and six children.

“Anchor’d in the haven of Rest”

Souvenir maker unknown

20th centuryOn loan from Glenn A. Hennessey, who represents Jabez Smith, Jr. in the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut

Jabez Smith, Jr., served as lieutenant of marines on the Continental ship Trumbull, perishing aboard ship in 1780 in a renowned battle with the British privateer Watt. An officer who participated wrote of the engagement, “It is beyond my power to give an adequate idea of the carnage, slaughter, havock and destruction…I hope it won’t be treason if I don’t except even Paul Jones…we may dispute titles with him.” Smith was laid to rest in Boston’s Granary Burying Ground, where today he lies near Crispus Attucks and Paul Revere. His headstone was topped with a handsome bas relief artwork depicting the ship Trumbull, a carving which has since become a symbol for the cemetery and reproduced on a variety of souvenir plaques, memorializing the grief felt for all the fallen patriots.

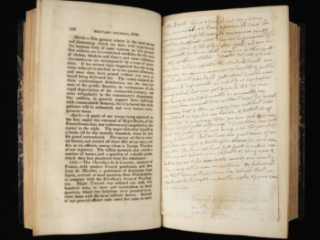

A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783

James Thacher

Boston: Published by Richard & Lord, 1823The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Tipped into this family copy of Thacher’s Military Journal is a page from his original diary that reads: “We have been several times without meat for several successive days & then as many days without bread, & without forage for our horses, & destitute of medicine & necessary stores for our sick soldiers. These complicated sufferings & privations are such that the patience of our army is on the point of being exhausted. But we have one great consolation, we have a Washington for our Commander. In him we have full faith & entire confidence we believe him capable of doing more & better for us & for the cause of our country than any other man in existence.”

Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia owned by James Tilton

Made by Jeremiah Andrews (d. 1817)

ca. 1784-1791The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Elizabeth Tilton Beaudrias, 2021

James Tilton, a doctor from Dover, joined the Delaware Regiment as a surgeon in January 1776. He witnessed the battles of Long Island and White Plains, and the retreat through New Jersey. In April 1777, Dr. Tilton was appointed as a Continental Army hospital physician and served in that role until the end of the war. He is most renowned for insisting on separating the sick from the wounded to prevent the spread of disease. After the war, Dr. Tilton joined the Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati and was elected its first president. This gold and enamel Eagle insignia, owned and worn by Dr. Tilton, was one of the first Society of the Cincinnati insignias made in America and represents his membership in the Society and his service during the war.