Ken Burns’s The American Revolution presents the war for independence as a defining event with consequences that reached far beyond the thirteen colonies. At the moment of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, the film underscores this significance with the observation that “the world would never be the same.” Some reviews have noted that while the film suggests the Revolution reshaped the wider world, it does not explore that global impact in detail. The experiences of the French officers who served in America help fill that gap. Their letters, journals, engravings, and portraits show how the war quickly grew into an international story and how its outcome reverberated across the Atlantic. Many of these firsthand accounts survive today because they were preserved by the American Revolution Institute, which maintains a rich collection of French officers’ writings and artifacts. For these men, the American Revolution was not only an American struggle but part of a larger shift in world affairs.

Journal of Robert Guillaume Dillon, 1780-1781

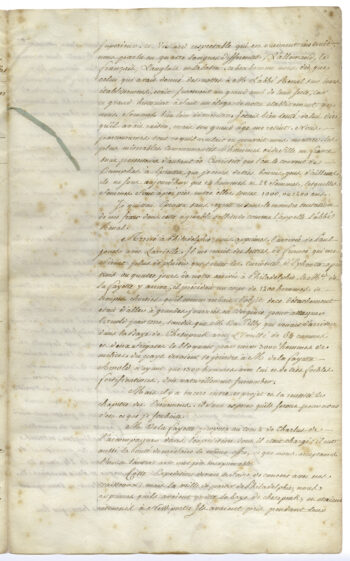

Robert-Guillaume, baron de Dillon (1754–1837) left one of the most vivid French records of the American campaign. His journal describes the march toward Yorktown in 1781 and includes a striking account of his meeting with George Washington at New Windsor, where he was impressed by the general’s bearing and command. Dillon also recounts his wounding near Gloucester, Virginia, during the final operations around Yorktown. His writing blends battlefield observation with social commentary, noting both the character of prominent American leaders and the customs he encountered while traveling through the colonies. For Dillon, the Revolution was a lived experience that revealed how American and French forces worked together to bring the war to its decisive close.

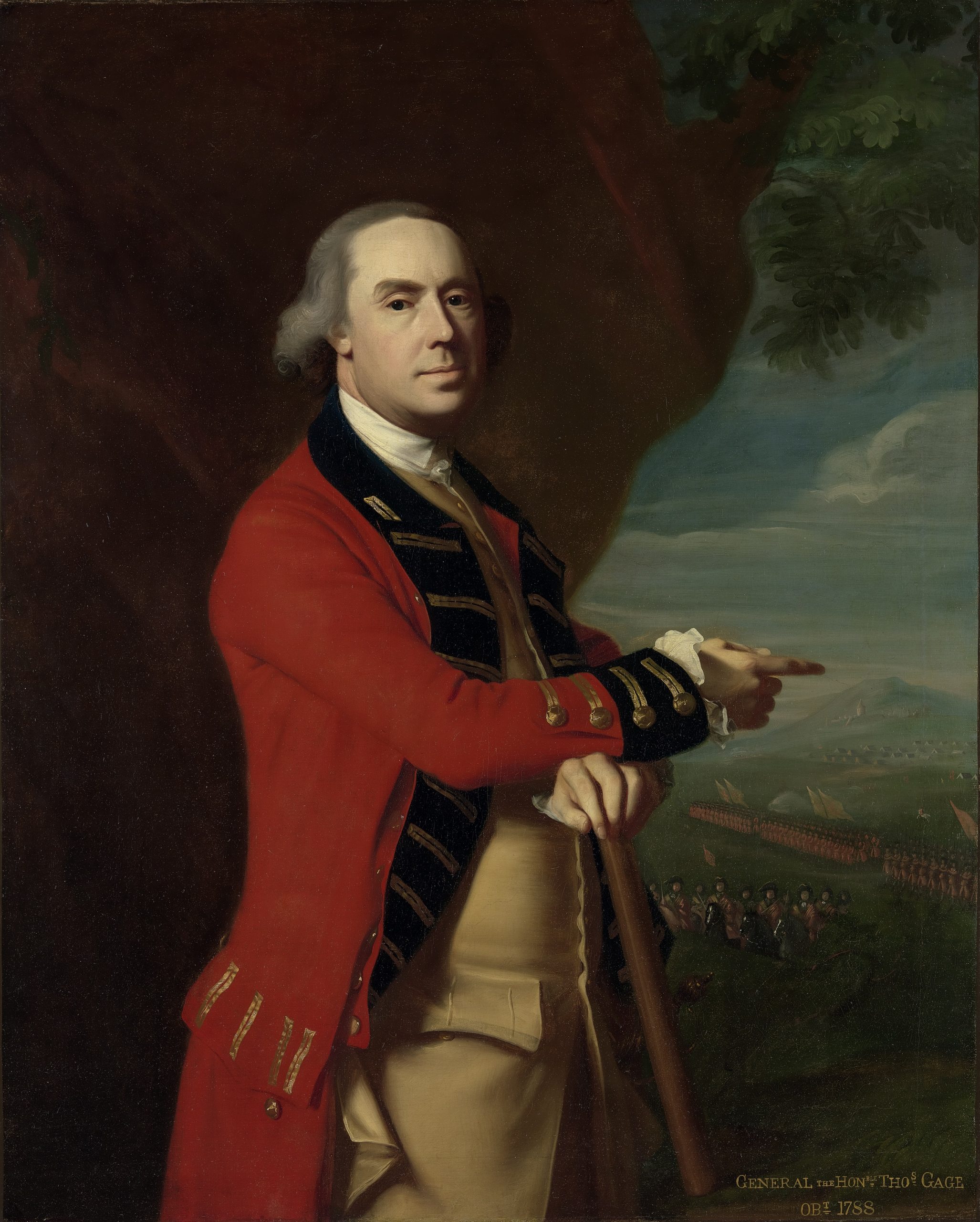

Claude-Anne de Rouvroy, marquis de Saint-Simon-Montbléru (1743–1819) played a central military role in the Yorktown campaign. As commander of the French left flank, he helped seal off Cornwallis’s potential escape route toward Williamsburg. Although severely wounded during the siege, he remained at his post and later stood with the allied generals at the formal British surrender. A portrait of Saint-Simon created after the war shows him proudly wearing the insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati, evidence of the lasting bonds formed between French and American officers. His later life, which included fighting revolutionary forces in Europe and serving in the Spanish army, demonstrates how deeply the American War for Independence intersected with the broader political upheavals that swept across the continent.

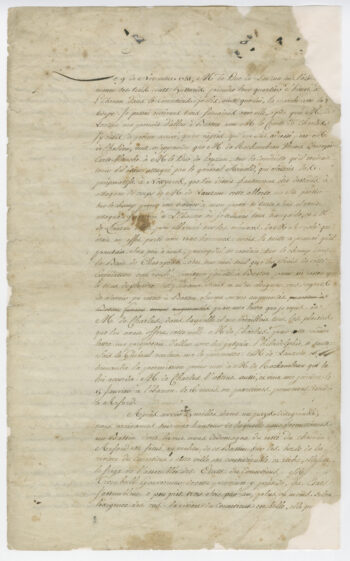

“Notes relatives aux mouvemens de l’armee françoise en Amerique” by François-Ignace Ervoil d’Oyré

François-Ignace Ervoil, chevalier d’Oyré (1739–1798), an officer in the royal corps of engineers, contributed essential technical expertise to the allied victory. His notebooks document the engineering work that advanced the siege trenches toward the British defenses at Yorktown, including the preparations that enabled the capture of key redoubts. He also recorded the allied march south and the memorable stop at Mount Vernon, where Rochambeau’s army reunited with Washington at his home. Oyré’s meticulous notes reveal the logistical complexity underlying the Yorktown campaign and show why success depended on careful coordination between French and American forces.

Jean-Baptiste Dupleix de Cadignan (1738–1824) preserved one of the most detailed French accounts of the war. His two-volume journal includes a day-by-day chronicle of the Yorktown siege, a full transcription of the Articles of Capitulation, and a description of the surrender ceremony in which British officers attempted to present Cornwallis’s sword. Dupleix’s writings make clear how French forces understood their role in securing American independence and how closely they observed the unfolding of events that would later become foundational moments in American history. His journal also illustrates how extensive French involvement was, extending from the Caribbean to the Chesapeake.

François-Jean de Beauvoir, marquis de Chastellux, by Jacques-Philippe Voiart, 1787

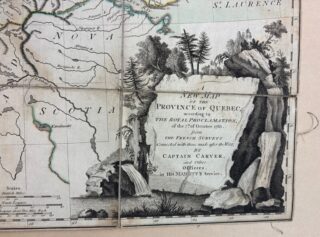

François-Jean de Beauvoir, marquis de Chastellux (1734–1788), a major general and philosopher, helped interpret the American experience for European audiences. Fluent in English and serving as the chief liaison between Rochambeau and Washington, he recorded reflections on American landscapes, society and politics during the allied march to Yorktown and in months of travel afterward. His published account of these travels introduced European readers to American culture and governance, including his observations of Virginia’s Natural Bridge, which he studied with scientific interest. Chastellux’s writings helped frame the Revolution as an event that raised questions about freedom, nature and political authority in ways that resonated across the Enlightenment world.

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) became the most famous French participant in the American cause and a symbol of the Revolution’s international character. As a young major general in the Continental Army, he commanded troops that helped pin Cornwallis at Yorktown before Washington and Rochambeau arrived. His success in America shaped his political vision in France, where he became a leading advocate for constitutional reform and authored the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Lafayette’s lifelong commitment to liberty, along with his correspondence with Washington and his celebrated return tour of the United States in 1824, shows how deeply intertwined French and American memories of the Revolution became.

Manuscrit des memoires politique et militaires du marechal de Rochambeau, 1725-1807

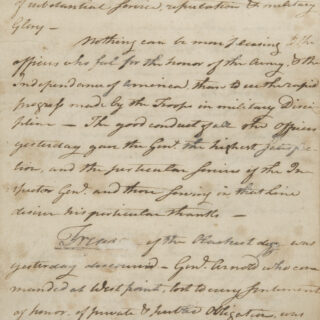

The war also had profound consequences for France itself. Supporting the American cause placed heavy financial strain on the French government and contributed to the crisis that led to the French Revolution in 1789. Many officers who served in America returned to a country in turmoil. Some, like Admiral Charles Hector, comte d’Estaing (1729–1794), were executed during the Terror. Others, including Saint-Simon, fought against revolutionary forces and later served in foreign armies. Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau (1725–1807), narrowly avoided execution and later wrote about his American experiences with Washington as he tried to understand the political upheavals around him. Their writings show that the ideals they encountered in America became part of the debates in France about liberty, loyalty and the future of the state. Burns emphasizes that revolutions can lead to unpredictable outcomes, and the experiences of these French officers demonstrate how the American Revolution helped set major changes in motion in Europe.

Together, the experiences of these officers illustrate how Burns’s line that “the world would never be the same” is grounded in historical reality. The war drew European powers into its orbit, produced new political conversations in France, created durable ties among veterans on both sides of the Atlantic, contributed to the pressures that sparked the French Revolution and showed that established political orders could be successfully challenged. Critics sometimes suggest that Burns’s film leaves the meaning of the Revolution open-ended. The French evidence helps explain why. The Revolution’s impact was not limited to America. It reshaped identities, institutions and governments across the Atlantic world. For the French officers who marched to Yorktown and later witnessed upheaval in their own country, the American Revolution marked the beginning of a broader era of political change that affected nations on both sides of the ocean.

Thomas Lannon

Library Director