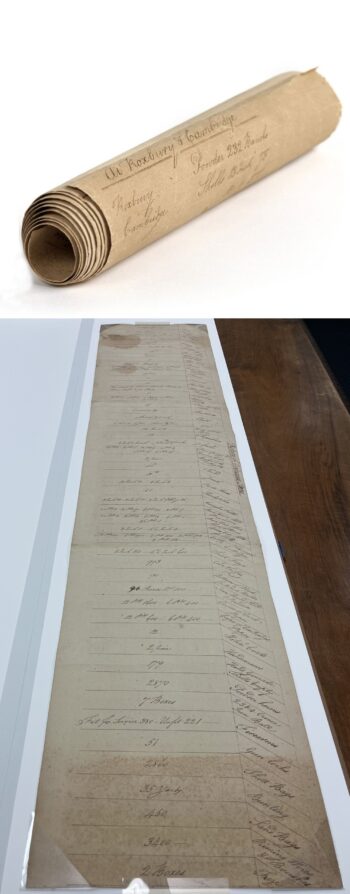

“Return of Ordnance Stores,” January 1, 1777, before and after conservation. The flattened roll of three joined sheets of cartridge paper is over four feet in length.

Nathaniel Barber, Jr.’s “Return of Ordnance Stores,” compiled in Boston on New Year’s Day 1777, is an extraordinary four-foot-long manuscript that preserves a rare and detailed accounting of the cannons, carriages, powder, shot and military stores on which the revolutionary cause depended. Rolled up like a scroll and designed to be unfurled across a table, Barber’s return presents more than fifty line items of ordnance distributed among Boston, Roxbury and Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the close of 1776. Particularly striking is the tally of gunpowder, 344 barrels—a perilously small reserve for an army then fighting across multiple states. Following the amount of powder, there are accounts for supplies such as small arms, mortars, field artillery and even grenades. Though the paper now shows stains, tears and the loss of several lines at the bottom, the ink remains strong and legible, preserving Barber’s meticulous accounting of Boston’s transformation from battleground to arsenal. A recent conservation project to flatten the “Return of Ordnance Stores” will allow for information on the return to be closely studied in the research library of the American Revolution Institute.

In the eighteenth century, ordnance typically meant artillery and munitions such as cannons, muskets, rifles, powder and shot. A return was a written account, usually in tabular or columnar form, that returned information for military administration up the chain of command. It was a standardized way to track men, supplies, weapons and provisions. This return of ordnance stores presents in columnar format all the military storage held in and around Boston, the headquarters of the Continental Army’s Eastern Department, in late 1776. The document records the fragile system of logistics for the Continental Army at a moment when the survival of the Revolution was still in doubt.

This return was signed by Nathaniel Barber, Jr., who bore the rank of deputy commissary of military stores in Boston, probably reporting directly to Artemas Ward, the first commander in chief of American forces during the Revolutionary War. Barber was a merchant whose commercial experience translated directly into the logistical demands of war. The son of a prominent Boston merchant and patriot, he began serving as the commissary of ordnance stores in April 1776, one month after British troops evacuated Boston. In preparing the return of January 1777, Barber exemplifies the many mid-level administrators whose names rarely appear in popular histories but whose diligence provided the backbone of revolutionary administration. His careful enumeration of powder and supplies reminds us that independence was sustained not only by generals and soldiers but also by clerks and merchants who mastered the indispensable arts of logistics.

The data is recorded in ink across three joined sheets of cartridge paper. Cartridge paper was a relatively coarse, high-quality paper originally manufactured for making the paper tubes that held measured charges of gunpowder for muskets and artillery. Paper was a strategic commodity during the Revolution. The Continental Congress and individual states recognized that without a steady supply of paper, they could not issue currency, commissions, military orders or newspapers. Several state legislatures including Connecticut and Pennsylvania even passed laws to exempt papermakers and printers’ essential workmen from militia drafts.

The survival of this return is due to Major General Artemas Ward, one of Massachusetts’ foremost revolutionary leaders. Born in 1727 and educated at Harvard, Ward had already served as a legislator, farmer and veteran of the French and Indian War when the crisis of 1775 thrust him into command of the provincial forces besieging Boston. He established and maintained the lines that held the British within the city until George Washington’s arrival. Ward continued to serve as commander of the Eastern Department of the Continental Army, headquartered in Boston, until his resignation in 1777. He retained Barber’s return in his personal document box, where it remained for decades. After his death the papers passed to his daughter Sarah and through her to later generations of the Ward family. The manuscript was noted in a 1910 article on Ward’s papers, providing a secure chain of custody across more than two centuries. This provenance links the clerical labors of Nathaniel Barber with the generalship of Artemas Ward, tying the return to two figures whose service was vital to the Revolution’s survival.

Section of “Return of Ordnance Stores,” January 1, 1777

Nathaniel Barber, Jr.’s “Return of Ordnance Stores” is more than a bureaucratic tally. It is a vivid reminder that the American Revolution was fought as much with ledgers and lists as with muskets and cannon. Its neat columns and measured handwriting reveal the precarious logistical foundations of independence, while its preservation in the Ward family papers connects it to the leadership that guided Massachusetts through the first years of war. Few revolutionary manuscripts combine such detailed content, compelling provenance and evocative physical presence. This remarkable return offers us a material witness to the Revolution’s precarious beginnings and to the administrative diligence that helped secure American independence.

Returns of this kind were once ubiquitous. Eighteenth-century armies depended on them to track men, arms and supplies. Thousands were created in the course of the war, yet few survive, particularly large-scale departmental returns like Barber’s. Most were discarded once their immediate purpose was served. The rarity of this document enhances its historical value. The return offers a window into the material resources required to sustain the Continental Army and illustrates the effort to build an administrative structure capable of supporting independence. Rolled into a scroll and stored for over two hundred years, the information from the document has been difficult to access. Thanks to recent conservation efforts, the return will be accessible to researchers on the American Revolution.