In the library of the American Revolution Institute, history surrounds on the shelves. Among the collections are works that help tell the story of the alliance between France and the United States, one of the most important turning points in deciding the Revolution. This partnership, formalized in February 1778 with the Treaty of Alliance, was more than a military arrangement. It was a meeting of political ideals, strategic necessities and mutual hope for reshaping the balance of power in the Atlantic world.

The library holds printed and manuscript material from before the alliance through to the war’s conclusion after the Franco-American victory at Yorktown and the establishment of the Society of the Cincinnati. From its founding in 1783, the Society included French officers who had served in America under Rochambeau, d’Estaing and Lafayette. This bond was deliberate. The Society wasn’t simply a fraternal group for Americans, but a transatlantic order intended to promote and cherish the ideals and national honor for which these individuals had fought.

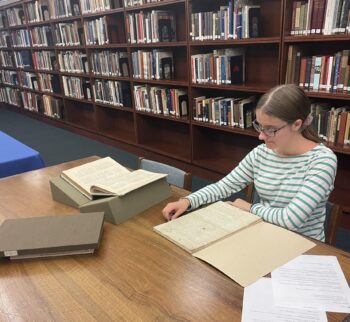

This summer, we were happy to continue the Society’s tradition of French-American exchange and welcomed a library intern from France to work with collections related to American forces and their French allies’ role in securing independence for the United States. Alice du Gardin, a master’s student at HEC Paris, was in Washington, D.C., for much of June and July and helped library staff process and translate manuscript materials. Among the items Alice helped translate were the journals of Robert Guillaume Dillon. Baron de Dillon served as mestre de camp of the régiment de Lauzun-Hussards and lieutenant-général during the Revolutionary War. He was also an original member of the French Society of the Cincinnati and kept a journal that covers the period from November 1780 through the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781.

Alice du Gardin, 2025 Research Library intern

“In his Journal, Dillon reports his memories about his time in America during the war. Unlike the memories of Rochambeau, this manuscript deals with personal and lived experience. Therefore, it provides us with broader information about what the life of a high-ranking officer could have been during the war—which it is very different from the experience of soldiers, for example.

During his time in America, Dillon didn’t only fight; he also travelled a lot, especially in the Northeast, and encountered many people, including George Washington. That’s why his memoir sometimes sounds more like a travel diary than actual military memories. He also shows a good sense of humor and a taste for Roman-like narration, which can lead us to wonder if some parts of the memories weren’t a bit exaggerated.

Dillon was born in 1754. He was from a military family whose name had been given to a regiment (the Dillon regiment). He entered the army in 1765, aged fifteen, and quickly climbed up the military ladder until he was promoted colonel of the Dillon regiment in 1768.

Robert Dillon became captain-commander in the Legion of Foreign Volunteers of the Navy in 1778 and fought under the Duke of Lauzun in the capture of British trading posts in Senegal in January 1779. Promoted to colonel in June 1779, he was appointed second colonel of Lauzun’s Legion in April 1780.

Wounded in a duel shortly before sailing for America in April 1780, Dillon later fought another duel with the Vicomte de Noailles. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Gloucester on 3 October 1781, leading 150 hussars against 400 British dragoons. For his service in the American campaign, he received the Cross of Saint Louis in 1783. At the end of the war, he came back to France, just a few years before the French Revolution broke out. Having chosen to stay loyal to the king, he encountered numerous obstacles in his career. He died in 1839.”

-Alice du Gardin, July 2025

Selected Extracts and Translations

(see also English translation, Jane L. Bush, 2020.)

At the beginning of the journal, Dillon narrates his encounters with General Washington and Eliza Hamilton:

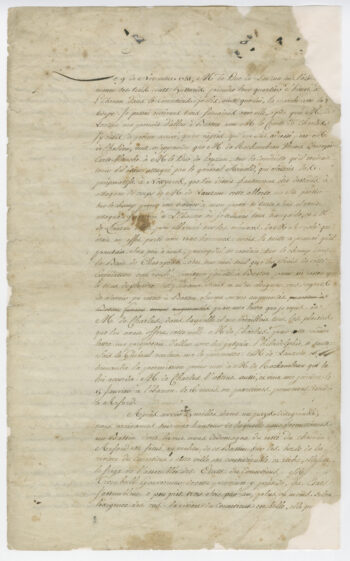

Journal of Robert Guillaume Dillon, 1780-1781, page 1

After having walked almost one mile, we arrived at the house where the hero of the Revolution, for whom my astonishment and my admiration rose with each moment, was staying. It was around five o’clock and he was still at his dessert; the Marquis de Lafayette (Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, marquis) was at the table with him. We withdrew with discretion when the Marquis, who had without any doubt already been notified that there were French officers at the door, ran after us and, recognizing Mr. de Charlus who was his friend, led us immediately to the dining room and introduced us to the General. Mr. Washington offered his hand to us affectionately; I presented mine with a respectful bow, after which he turned to Mrs. Washington (Martha Washington) to whom he introduced us, as well as to General Howe (Robert Howe) and Colonel Jackson (Henry Jackson) who were dining with him.

Mr. Washington completely fulfilled the impression I had made of him. It seemed that nature was pleased to lavish upon him what she often grants with whimsicality. She bestowed upon him a general effect which seduces accordingly when one gazes upon him; his large personality and his soul are etched in his features. I would have recognized the General among a thousand officers of his army without any trouble. He is one of the most handsome men I have ever seen, but it is a kind of handsomeness that emanates more from his soul than from his outward appearance. His ways are noble and easy, without embarrassment nor affectation. Speaking little, but with strength, his voice is gentle without losing what the Majestic gives to the expressions of a voice, strong and clear. We sat down at the table with him and drank several toasts.

After having dined, we moved to the adjoining room where we stayed until supper-time. I had a fairly long conversation with his Excellency. As it was not for me to ask questions, I let him take the lead. The conversation turned to the country through which I had just travelled; he seemed delighted by the praise I made of it. Mr. de Charlus, who had been to Boston, spoke to him, with admiration, about the places which had inspired him where he had made his first campaign against the British.

He laughed a lot with us about the fear of the English, saying that if they had turned out just two thousand men he would have been obligated to retreat.

Someone came to let us know that supper was served. We passed through to the dining room where several minutes later Mrs. Washington arrived, accompanied by Mrs. Hamilton (Elisabeth “Eliza” Schuyler Hamilton), a young and pretty woman, recently married to Mr. Hamilton (Alexander Hamilton) General Washington’s personal aide-de-camp. The young man is witty and talented, and speaks French admirably. We retired shortly after having dinner.

Dillon then travels through many American cities and describes many places he visited, including Philadelphia and Baltimore:

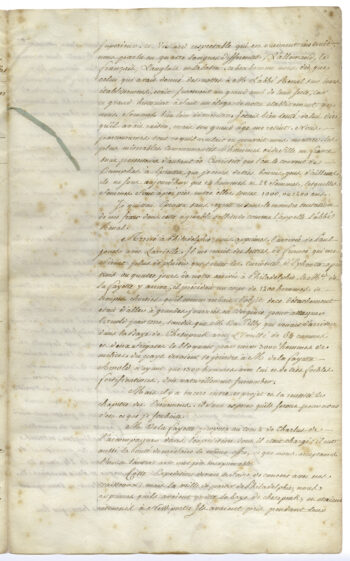

Journal of Robert Guillaume Dillon, 1780-1781, page 13

Philadelphia is perfectly beautiful and orderly; all houses there are made of brick. The place where Congress assembles is a really beautiful building. I lodged at the residence of the Spanish Ambassador; the house he occupies would be as beautiful in Paris. Philadelphia is built on the model of the city of London; one is surprised to see the large number of beautiful ships (there are more than 150 vessels docked at the port.) If America wins [the war], Philadelphia, in a hundred years, will be equal, at least, to London or Paris. We were charmingly received by Mr. le Chevalier de la Luzerne (Anne-César, chevalier de la Luzerne), Minister Plenipotentiary of France, and fêted with a number of balls and very pleasant gatherings. The women have almost all adopted French fashions. Several of them surprised me by the taste and the style of their adornment; their shoes impressed me the most. They are, in general, much better heeled than the women in our largest cities. They all dance terribly but, nevertheless, it’s all the rage to dance French contra dances. I noticed that, with their unpretentious look, they are, at the very least, as fashionable as are our ladies. But they limit their intelligence to flirting, gallantry still being in its infancy. One must hope that their marital partners will take charge of their education and that, from here, in ten to twelve years, they will at least be discreet and will start to make themselves understood in the houses of Philadelphia.

After three weeks of my visit, Mr. de Charlus and I decided to travel through Pennsylvania and Maryland until Annapolis which is situated on the other side of the Chesapeake Bay.

[…] [The Chesapeake Bay is] one of the most beautiful bays in the world. It forms a basin of about seven or eight leagues in circumference at the location from where we saw it. The Susquehanna is, after the Potomac, the most beautiful of all the rivers which flow into this bay. While crossing the river, we saw an astonishing number of all kinds of birds, some of which were eagles, who walked very solemnly on the ice floes which were carried along by the river. Twelve miles from there we bedded down in the town of Buck.

The [15th] we arrived in Baltimore, the most commercial and wealthiest town of all those situated on the Chesapeake Bay. We stayed there a day and a half. Its port is likely to have all possible comforts and will certainly be one of the largest on this continent. There are about four thousand souls in the town, and it has only been in the last thirty years that there have been more than twenty houses. We saw nice tobacco shops, etc.; about forty small vessels. The port is defended by a bad fort. We counted upon going to Annapolis but we were assured that all the inhabitants had deserted it and had retreated to the countryside by fear of an attack by Arnold, and someone also told us that the town was much less notable than it used to be but, as it was the county seat of Maryland, all the wealthy people of the province had beautiful homes there where they spent winter and [had] created a pleasant community.

About the Library

The research library of the American Revolution Institute houses more than fifty thousand rare books, manuscripts, prints, broadsides, maps and modern reference sources, and is one of the most important resources in the world for advanced study on the Revolution. The library welcomes researchers to use the collections by appointment and supports scholarship by offering several research fellowships each year to graduate students and advanced scholars. To learn more, and make an appointment click here.