This lesson asks students to consider and analyze two very different depictions of the Battle of Princeton created by contemporaries. The first image is James Peale’s painting, The Battle of Princeton. Peale’s Princeton is uniquely important, because it is the only painting of a Revolutionary War battle painted by a participant. The second is John Trumbull’s The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777.

The goal of the lesson is to encourage students to consider why these artists, and artists in general, depict contemporary events in different ways. A premise of the lesson is that artists depict events to convey ideas about those events that were relevant to contemporaries but which may not be clear to us, more than two hundred years later. The lesson asks students to treat the paintings as original sources from which we can discover how contemporaries — beginning with the artists of the works under consideration — imagined the events depicted in the paintings.

To analyze the two images, students will need to understand the basic narrative of the Battle of Princeton, which may be best accomplished with a short lecture. Questions to pose to students about the images are indicated in bold type. These can be addressed in an open classroom discussion, in Think/Pair/Share format, or in a writing exercise for students to complete alone. If the teacher chooses the latter, the questions can be introduced for the students to consider on their own, with the explanation that some of these questions will appear in a brief writing exercise at the end of the lesson.

The Battle of Princeton was a turning point in the Revolutionary War. In the first stage of the war, the patriots had driven the British army and navy out of Boston. The British departed in March 1776. For a few months, the colonies were free from British occupation. In July 1776 the Continental Congress declared the colonies independent of Britain. But the war was far from over.

The war entered its second stage in August 1776, when the British returned with a powerful fleet and an army of 36,000 men, including British troops and mercenaries — hired soldiers called Hessians — from several independent German states. This was the largest army any European country had ever sent overseas. The goal of this invading force was to crush the Continental Army and reconquer the colonies for Britain.

The first British target was New York City, which had a fine harbor that would be a perfect base for military operations. The Continental Army did its best to defend the area, but was driven out in November 1776, having suffered heavy losses in a series of battles. The army retreated across New Jersey and into Pennsylvania, putting the Delaware River in between themselves and the pursuing British army.

The British army did not cross the Delaware to crush what was left of Washington’s army. The British commander, General Sir William Howe, knew that the enlistments of most of Washington’s army would expire on December 31, 1776. He expected that Washington’s soldiers, disheartened by months of defeat, would refuse to reenlist and go home. With an army too small to resist the British, Howe believed the rebels would accept their defeat and return to British rule. He believed the war would be over by spring.

Howe was prepared to wait a few months to complete his assignment and end the war. In the eighteenth-century, armies rarely campaigned in winter. The weather was cold and unpredictable, dirt roads were often muddy and impassable, supplies were hard to move, and soldiers were vulnerable to illness. Generals preferred to establish winter quarters, occupying towns or building wooden huts where their soldiers could do their best to stay warm and healthy until spring.

This is exactly what Howe did. He spread his army out across New Jersey for the winter. He assigned a force of Hessians to occupy Trenton, a town on the Delaware River, and ordered other units to occupy other towns along the roads leading back toward New York, from which the army’s supplies were brought.

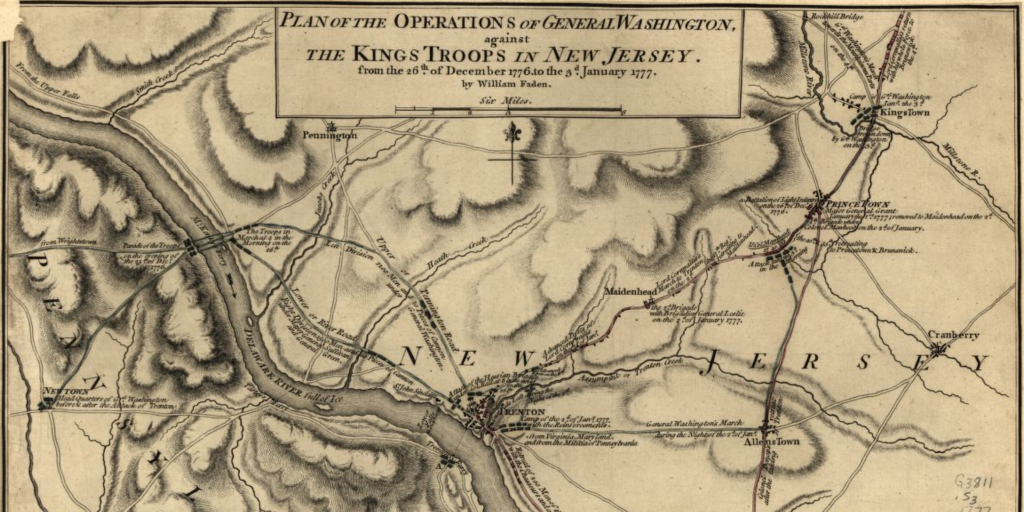

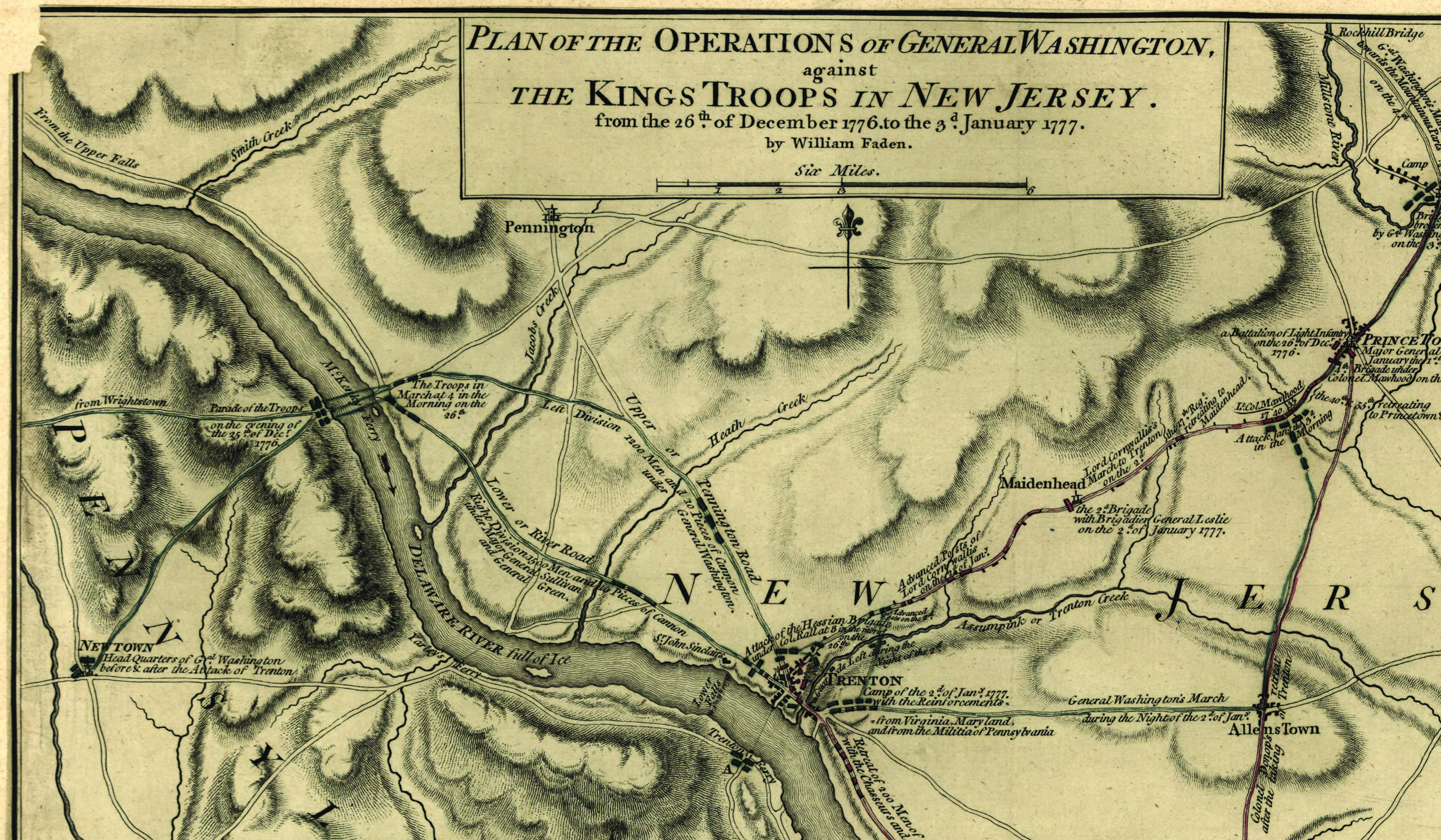

Howe had underestimated George Washington, who saw a chance to turn the war around. On Christmas Day, Washington’s army marched to the Delaware River and crossed during the night. The next morning the Continental Army surprised the Hessians in Trenton and forced them to surrender, then recrossed the Delaware to safety. It was the victory Washington needed. Encouraged by success, many of his soldiers agreed to reenlist. The Continental Army did not dissolve as Howe had expected.

On December 30, Washington led his army back across the Delaware and reoccupied Trenton. Howe sent a large force under General Charles, Lord Cornwallis, to attack Washington. The two forces faced one another across a creek near Trenton as night fell on January 2, 1777. Cornwallis planned to attack Washington and destroy the Continental Army the next morning. But when morning came, he was surprised to find that Washington’s army had gone, leaving campfires burning to fool the British into thinking they were still here.

During the night, Washington’s army quietly marched north to attack the British force occupying the town of Princeton, which was behind Cornwallis on the road back to the main British supply center in New Brunswick. Washington hoped to achieve the kind of surprise at Princeton that had make his attack on the Hessians at Trenton such a dramatic success.

It didn’t work out as Washington planned. During the night Cornwallis had ordered British commander at Princeton, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood, to march south to join his army at Trenton. As Mawhood marched south with two British regiments, he caught sight of Washington’s army about two miles south of Princeton. The two armies were on parallel roads, Washington headed north, Mawhood headed south. Not knowing how many Americans he was facing, Mawhood turned around and marched back toward Princeton, where a third British regiment was stationed.

Washington ordered troops under Brigadier General Hugh Mercer to attack Mawhood. Mercer and his men advanced toward the British line of march. Mawhood responded by detaching part of his force to attack Mercer. They met in an orchard owned by William Clarke. Mercer’s men drove the British back, then took up a defensive position along a fence, supported by two cannons commanded by Captain Daniel Neil, and fired as the British troops mounted a counterattack. The British sustained heavy casualties but kept advancing with bayonets fixed on their muskets. Mercer’s men lacked bayonets and were unprepared for hand-to-hand fighting. The American line disintegrated. The British overran the American position and captured Neil’s cannons, turning them on the Americans.

Mercer tried to rally his men as they fled back toward the main body of Washington’s army, but his horse was hit by British fire and collapsed. As he fell from the saddle, Mercer was surrounded by charging British soldiers who demanded he surrender. Mercer tried to fight, instead, and was repeatedly bayonetted and clubbed with the butt end of British muskets. His attackers left him for dead and charged on.

A brigade of Pennsylvania militia under Colonel John Cadwalader came up to support Mercer and blunt the British attack as the enemy crossed the frozen field separating the William Clarke orchard from the farmhouse of Thomas Clarke, which stood on a low rise a few hundred yards away from the orchard. Cadwalader’s men were not prepared. Many of them fell back beyond the Thomas Clarke house, leaving two cannons commanded by Captain Joseph Moulder to contest the British advance. Moulder’s guns were supported by survivors of Mercer’s brigade, who exchanged volleys with Mawhood’s men as the British commander organized his men to drive the Americans from the field.

George Washington arrived at the scene at that moment. He rallied Cadwalader’s men and put them, along with New England Continentals, into a line of battle near Moulder’s Battery. Washington then personally led the American line forward, bravely taking a position in front of the American line. The British and American lines exchanged volleys as Moulder’s Battery continued to fire on Mawhood’s men. Then Washington pressed forward. The British line wavered, then broke in confusion. Some of the British fled south toward the main body under Cornwallis, while others made their way north into Princeton, where another regiment was stationed. Washington’s army pursued the fugitives in both directions, capturing prisoners on the roads and forcing the surrender of 194 British soldiers who took refuge in Nassau Hall, the main building of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

The Battle of Princeton was George Washington’s first battlefield victory over British troops. He had forced the British out of Boston in 1776 without a fight, and had beaten the Hessians at Trenton on December 26, but Princeton was the first time he had the pleasure of driving British soldiers from a battlefield.

Knowing that Cornwallis must be marching north from Trenton, Washington made another bold decision: instead of retreating back across the Delaware, he marched north through New Jersey and established his winter quarters at Morristown, in the New Jersey hills west of New York City. This position threatened the British supply line south to New Brunswick. Unwilling to attack Washington’s fortified camp in the hills, British General Howe had little choice but to abandon New Jersey and withdraw to New York for the winter.

In the ten days between his first crossing of the Delaware on December 25, 1776, to the afternoon of January 3, 1777, when he marched north toward Morristown, Washington had blunted the British reconquest of the former colonies and rescued most of New Jersey from British control. He had deprived the British of the quick victory they had hoped for. The war would continue.

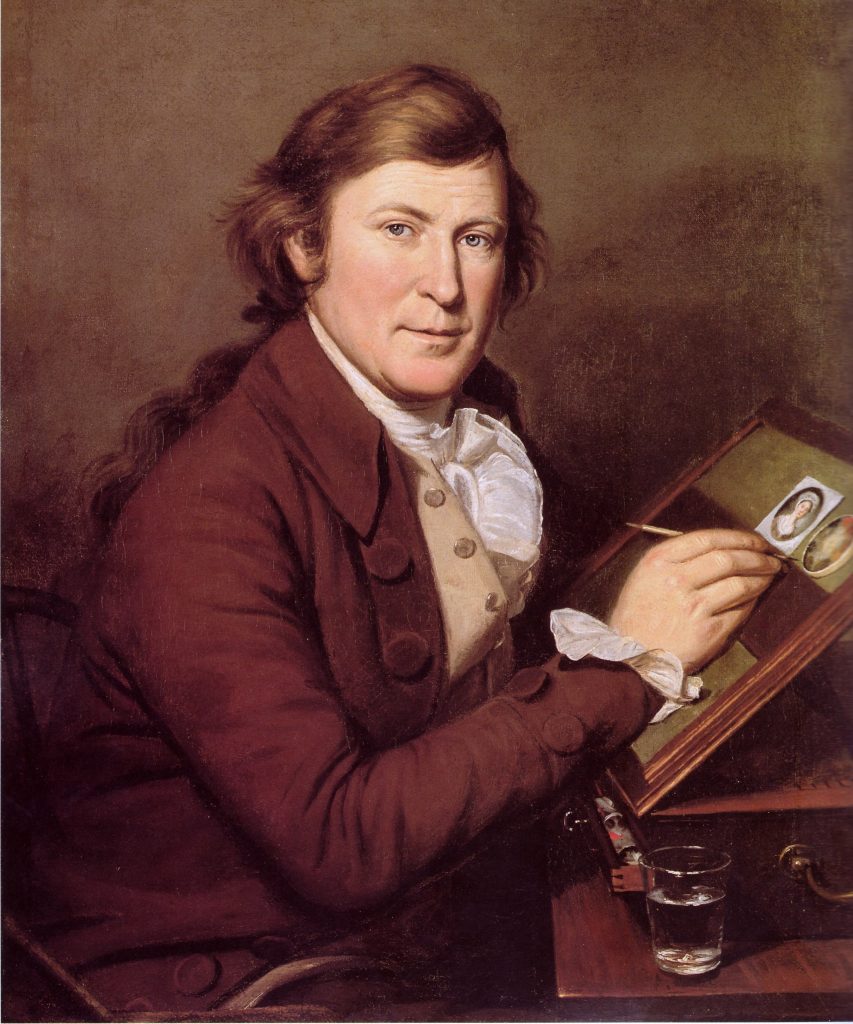

James Peale was the younger brother of Charles Willson Peale, a Philadelphia artist who became one of the most important American painters of the Revolutionary era. Charles trained to become an artist. James became a saddle maker, but gave up that trade to work with his brother as an artist in his Philadelphia studio. James became skilled at painting miniature portraits, but was never a great artist like his brother.

Both Peale brothers served in Washington’s army during the Princeton campaign. Charles was a lieutenant in the Philadelphia Associators, and James as an ensign in the First Maryland Regiment in the Continental Army. In 1779, Charles returned to the Princeton battlefield and made sketches of the site for use in the background of a portrait of George Washington. James may have used those sketches to supplement his own recollections of the battle while working on The Battle of Princeton, which he completed in 1782. William Mercer, the deaf-mute son of General Hugh Mercer, was an assistant in the Peale studio and may have worked with James on the painting.[/two_third]

James Peale’s The Battle of Princeton depicts the critical moment when Washington rode onto the battlefield, rallied Cadwalader’s Philadelphia Associators, and led them forward to attack the British.

The first question students should consider is a simple one: What is happening in the painting? Students will probably recognize several details, although the teacher will need to provide the background at each point that will make it clear that, despite the somewhat primitive style of the painting, James Peale was very careful to get details right.

-

- George Washington is at left center on a brown horse. We know this is General Washington because he is wearing a blue silk sash, which is an indication of his rank. Behind him someone is carrying a blue flag decorated with stars. This is George Washington’s headquarters flag. A flag of this design, though much smaller than the one depicted by Peale, is preserved in the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

- A cannon is firing at right center. This is a gun of Moulder’s Battery, which held off the British while Washington formed the infantry for the charge that won the battle. The five-man gun crew is depicted with care and accuracy. They include a spongeman (1) (holding the sponge) and loader (2), both at the front of the gun, a ventsman (3), who places the priming charge in the touchhole, a firer (4), who fires the gun but touching off the priming charge, and a senior gunner (5) who aims the piece and gives the orders. The senior gunner depicted is probably Captain Joseph Moulder.

- In the middle distance an American officer lies wounded beside a horse. This is General Hugh Mercer, who was left for dead by the British. As the Americans counterattacked they found Mercer alive and carried him to the nearby Thomas Clarke House, which was used as a field hospital. Mercer had several bayonet wounds and had been injured by musket blows to the head. He regained consciousness, but died nine days later.

- The British are arrayed in line of battle along the fence. They are too far away for Peale to have depicted them in any detail, but still within range of musket fire.

- Three American cavalrymen wearing brown jackets and hats with blue ribbons (two are seen behind Captain Moulder) are riding forward. They are wearing the uniform of the Philadelphia City Troop of Light Horse, a private volunteer cavalry unit.

- American infantry are coming up from the left to join the line and prepare to attack. Students may recognize that some wear the blue coats usually associated with the Continental Army, while others wear brown coats. American soldiers actually wore uniforms of various colors, though none wore red. The infantrymen in brown coats are from the Cadwalader’s brigade of Philadelphia Associators.

- George Washington is at left center on a brown horse. We know this is General Washington because he is wearing a blue silk sash, which is an indication of his rank. Behind him someone is carrying a blue flag decorated with stars. This is George Washington’s headquarters flag. A flag of this design, though much smaller than the one depicted by Peale, is preserved in the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

Students may be curious how we know details about these uniforms after nearly 250 years. In this case, a member of the Continental Congress, Silas Deane, wrote to his wife, Elizabeth, from Philadelphia on June 3, 1775: “The militia are constantly out, morning and evening, at exercise, and there are already thirty companies in this city in uniform, well armed, and have made a most surprising progress. The uniform is worth describing to you; it is a dark brown (like our homespun) coat, faced with red, white, yellow, or buff, according to their different battallions.” The facing of a uniform is a piece of fabric on the lapel, collar, cuffs or tails that identifies the wearer’s unit.

James Peale was very careful in depicting this uniform. If the students look closely they will see that the brown coats are faced with red (visible in this detail in the collar and tails of the coats). Red is the facing color used by the Second Battalion of the Philadelphia Associators. James was undoubtedly careful to include this detail because his brother Charles was a lieutenant in the Second Battalion and participated in the charge.

Charles Willson Peale kept a journal during the Revolution in which he made notes on all sorts of details, including how he assembled the clothes and equipment he needed as an Associator. The Quaker-dominated government of Pennsylvania, adhering to pacifist principles, had refused to raise militia at government expense. The Philadelphia Associators were a private organization, and every member had to provide his own uniform and equipment. Peale noted on July 22, 1776, that he “purchased 1 1/2 yd Brown Cloth for a Coat. pd. Mr. Riddle for a pr of white Briches.” Over the next four days he bought a cartridge box, a bayonet, a new steel ramrod for his musket, a belt and scabbard for his bayonet, and a strap for his musket. On October 9 he bought white linen to make a vest and pants, and he left all of the cloth with Joseph Tatem, a Philadelphia tailor, “to make Regmantles for me.” On October 16 he paid Tatem “for makg. & finding Trimimings for my waste Coat & Breeches.” Then on December 2, as winter set in, he paid the tailor for a “French great coat” and “swanskin.” The “swanskin” was not the skin of a swan. Swanskin was the name for a kind of thick cotton flannel used for winter underwear. On December 5 he bought a pair of “furd Gloves.” He was finally ready for a winter campaign.

The Associators marched to support the Continental Army as it retreated toward the Delaware River in early December. On December 7, Charles was at Trenton — attired in his new uniform — when the tired remains of Washington’s army arrived. “Suddenly a man staggered out of the line and came toward me,” Charles wrote in his autobiography. “He had lost all his clothes. He was in an old dirty blanket-jacket, his beard long, and his face full of sores . . . which so disfigured him that he was not known by me on first sight. Only when he spoke did I recognize my brother James.” The First Maryland Regiment had fought bravely around New York and had suffered heavy casualties. The hundred or so that remained were part of Hugh Mercer’s brigade.

The Associators marched to support the Continental Army as it retreated toward the Delaware River in early December. On December 7, Charles was at Trenton — attired in his new uniform — when the tired remains of Washington’s army arrived. “Suddenly a man staggered out of the line and came toward me,” Charles wrote in his autobiography. “He had lost all his clothes. He was in an old dirty blanket-jacket, his beard long, and his face full of sores . . . which so disfigured him that he was not known by me on first sight. Only when he spoke did I recognize my brother James.” The First Maryland Regiment had fought bravely around New York and had suffered heavy casualties. The hundred or so that remained were part of Hugh Mercer’s brigade.

These circumstances suggest a question: Why did James Peale paint The Battle of Princeton? Some artists painted works for profit, often secured by selling copies of the painting or engraved prints based on it. There is, indeed, a second painted copy of the painting, but it is believed to have been painted by the Peale’s assistant, Billy Mercer, who probably kept it for himself.

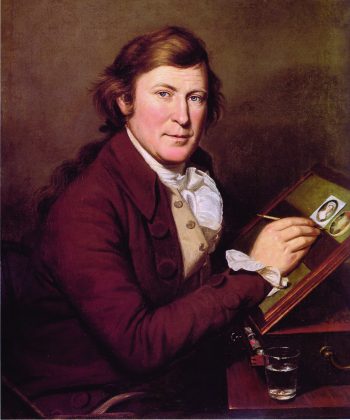

It seems most likely that The Battle of Princeton was painted for nothing more than the satisfaction of the artist, to memorialize a battle in which he and his brother fought. The two worked together for many years, and their close relationship is illustrated by the portraits they painted of one another, like this portrait of James working on a miniature portrait, painted by Charles in 1795.

After considering the details in the painting, students should consider: Does the fact that James and his brother Charles both fought in the battle make the painting a dependable depiction of what happened? Why or why not?

In general, the answer is that the fact that the artist and the brother with whom he worked were eyewitnesses lends credibility to the depiction of the battle. On the other hand, the painting was not completed until more than five years after the battle. Memories—even of dramatic events—fade with time.

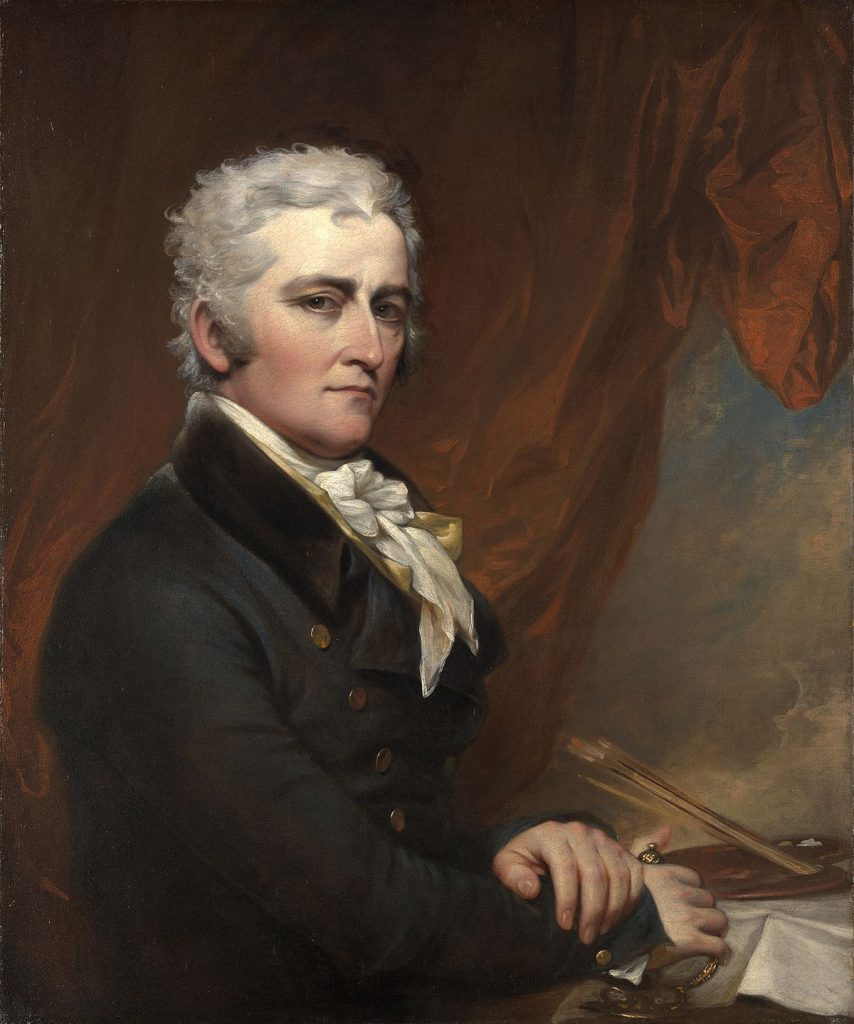

The second image to consider is one of the most famous paintings of a Revolutionary War battle. John Trumbull’s The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777 is one of a series of paintings of scenes from the American Revolution Trumbull painted between the 1780s and the 1830s, including depictions of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the surrender of the Hessians at Trenton, the British surrenders at Saratoga and Yorktown, and the presentation of the Declaration of Independence in the Continental Congress. Trumbull sold versions of some of these paintings to the United States government for display in the Capitol. He also had some of them engraved and printed and sold the prints to people who displayed them in their homes.

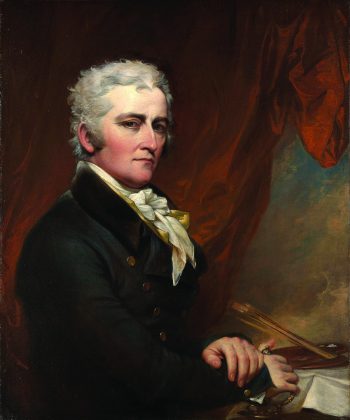

Trumbull was obviously a much more talented artist than James Peale. He was, in fact, one of the most important American artists of the Revolutionary generation. He was a member of a prominent patriot family and was educated at Yale. He served in the American army briefly, then resigned to study painting in London with Benjamin West, an American-born painter who had moved to Britain and established himself as the greatest painter of historical subjects of his generation. Charles Willson Peale and another famous American painter of the Revolutionary generation, Gilbert Stuart, also studied with West.

Trumbull started working on The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton in 1786, about the time he completed The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Trumbull worked on the painting off and on for forty-five years, leaving at least twelve sketches and three oil paintings. The definitive version is the one now owned by Yale University, which Trumbull completed in 1832. Of all of his paintings of scenes from the American Revolution, it was his favorite.

The first thing for students to consider is the title: Why did Trumbull call the painting The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton? This question reaches for the central premise of this lesson—that artists present historical scenes in ways that best convey their ideas about events. Often they seek to convey a fundamental truth about an event that could not be conveyed effectively in a literal depiction.

The first thing for students to consider is the title: Why did Trumbull call the painting The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton? This question reaches for the central premise of this lesson—that artists present historical scenes in ways that best convey their ideas about events. Often they seek to convey a fundamental truth about an event that could not be conveyed effectively in a literal depiction.

Students who paid close attention to the discussion of Peale’s The Battle of Princeton will remember that Hugh Mercer did not die in the battle. He was mortally wounded and died nine days later. Trumbull knew this, but he probably named the painting The Death of General Mercer in order to make Mercer a martyred hero like Joseph Warren, who died at the Battle of Bunker Hill. A title like “The Wounding of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton” would not have been as dramatic.

Having examined Peale’s The Battle of Princeton, students should consider: How are the two painting similar? What do they have in common? Both paintings depict:

-

- General Mercer wounded on the battlefield;

- George Washington rallying his troops and leading them forward; and

- an American gun crew, though in Trumbull’s Death of Mercer the gun is one of the two overrun by Mawhood’s charge.

How does Trumbull’s depiction of the battle differ from James Peale’s version of the battle? The superficial answer is that it is a much more refined work of art, but encourage students to look past this obvious fact. Several more thoughtful answers are possible, among them the fact that Peale depicted the battle from a distance, while Trumbull brings the viewer right into the action at its height and presents the combatants close up.

The most important difference between the two images students should grasp is that Peale’s The Battle of Princeton seems to depict a particular moment in the battle—the short period when Moulder’s Battery and a small number of infantrymen held Mawhood’s troops in check while Washington organized the charge that resulted in the American victory.

Trumbull’s Death of Mercer, by contrast, depicts several moments in a single composition. At left, Mawhood’s charging British overrun a battery of the Pennsylvania State Artillery and kill Captain Daniel Neil. A few feet away, Hugh Mercer struggles with his attackers. This took place at least a hundred yards away and minutes after the British overran the battery. Behind Mercer, Washington directs the victorious counterattack that occurred some fifteen or twenty minutes after Mercer was wounded, and another 150 to 200 yards away. Behind Washington are the mounted figures of Col. John Cadwalader and Dr. Benjamin Rush.

At far right, Trumbull balances his composition by depicting the mortal wounding of Captain William Leslie of the British Seventeenth Regiment of Foot. The composition might leave viewers with the impression that Leslie fell resisting the American counterattack led by Washington. In fact, Leslie died in the struggle in William Clarke’s orchard and was one of the first British soldiers to die in the battle. Lieutenant William Armstrong reported that Leslie “fell in the first fire.” Peter McDonald, Leslie’s servant, reported that Leslie was shot in the heart and died instantly. Trumbull used Leslie to symbolize the tragedy of the war. The young officer’s body was carted off the battlefield by the Americans and buried the next day with military honors in a cemetery several miles away. Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush, who had been befriended by Leslie’s aristocratic family when he was a young man studying medicine in Scotland, wept when he learned of the young officer’s death. He wrote letters of condolence to the family and later paid to have a tombstone erected over the young man’s grave.

Students who have examined Trumbull’s Death of Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill may recognize that the mortally wounded British Major John Pitcairn plays the same role as Leslie in The Death of Mercer at the Battle of Princeton. The death of each man symbolizes the tragedy of a war between Britons and Americans—peoples united by a shared past, a common culture, and many ties of family and friendship, but divided by principles that drove them inexorably to war. The tragedy of the war and the personal sacrifices made by both sides underscore the importance of the struggle and its consequences — the establishment of an independent republic, dedicated to ideals of liberty, equality, and civic responsibility.

Assessment

Think/Pair/Share-Provide 6-8 minutes for students to answer on paper the questions below. Then pair students up to discuss their findings and revise their written answers. Students will submit final written answers to the questions for evaluation. Alternatively, ask students to work on their own to answer these questions.

-

- James Peale finished his painting of the Battle of Princeton about 1782. John Trumbull began making sketches for his painting the battle in 1786. Trumbull probably never saw Peale’s painting, but he included some of the same incidents in the battle as Peale. What are they? What importance do you think the Peale and Trumbull attached to these incidents.

Both artists depict the wounded Mercer and Washington rallying his men to charge the British. Both artists sought to convey the idea that the battle — and the war for American independence — was won because men like Hugh Mercer were prepared to give their lives for the cause of liberty and independence. Both artists also sought to convey the importance of George Washington’s leadership to turning a near defeat into victory.

-

- Peale depicted a cannon commanded by Captain Joseph Moulder firing at the British. Trumbull depicted a cannon commanded by Daniel Neal being captured by the British and Neal being killed. Why do you think they made these choices? What were they trying to say about the battle? Are they presenting different messages?

- Peale depicted a cannon commanded by Captain Joseph Moulder firing at the British. Trumbull depicted a cannon commanded by Daniel Neal being captured by the British and Neal being killed. Why do you think they made these choices? What were they trying to say about the battle? Are they presenting different messages?

Peale’s painting appears to be his best effort to depict a critical moment of the battle in a literal way. Both Peale brothers saw Moulder’s Battery in action, and recognized how important it was in holding the British at bay while Washington organized the charge that won the battle. Peale’s painting is, in some ways, a tribute to Moulder and his crew as it is to Washington’s leadership, Mercer’s sacrifice, and the men of Charles Willson Peale’s battalion of Philadelphia Associators. The central theme of Trumbull’s painting is personal sacrifice for a cause. He depicts the death of Captain Neal because it fits this theme, as does the wounding of Mercer and the death of British Captain Leslie.