Interpreting Artifacts as Primary Sources

The aim of Objects of Revolution is to teach students how to interpret surviving artifacts of the Revolutionary era and relate them to the contexts in which they were made and used. Artifacts of the Revolution include a broad range of objects, everything from small tools, coins, clothing, furniture and weapons, to roads, ships and buildings. The things people made and used in the American Revolution complement the documentary and visual record and offer insights about life in the Revolutionary era that cannot be found in other sources.

The Great Seal of the United States

In this lesson, students learn how the Revolutionaries created the Great Seal and what the different symbols that make up the Great Seal mean, and will consider how those symbols have been used to represent our national identity since the Revolutionary generation.

An Eighteenth-Century Smartwatch?

Long before the advent of digital or print photography, portrait miniatures served as intimate keepsakes given by the sitter to a loved one to convey their affection and represent their bond. During the American Revolution, these tiny likenesses were carried by soldiers and public officials away from home, and worn by women as necklace pendants or wristlet ornaments. This lesson introduces students to the art of the portrait miniature, and invites them to envision twenty-first-century equivalents.

Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware

Emanuel Leutze’s painting Washington Crossing the Delaware was completed in Germany seventy-five years after George Washington’s legendary victory at Trenton, yet the painting has become perhaps the most iconic image commemorating the American Revolution. In this lesson, students will analyze the painting for themes of unity and diversity, and appreciate the historical contexts of both the depicted scene and the creation of the painting.

Verger’s “Four Soldiers”

King Louis XVI of France sent supplies and soldiers as part of the Franco-American alliance during the Revolutionary War, including French officer Jean Baptiste Antoine de Verger who arrived with General Rochambeau’s troops. While in Yorktown, Verger created a watercolor depicting soldiers in the Continental Army now nicknamed “Four Soldiers.” In this lesson, students will investigate this image for indicators of diversity within the ranks of the Continental Army and explore how the common ideal of liberty unified American soldiers despite their regional differences.

Washington’s “Purple Heart”

George Washington created the Badge of Military Merit—the first American military decoration for enlisted men—on August 7, 1782. Soldiers were honored with the award for “instances of unusual gallantry…extraordinary fidelity and essential service.” This lesson invites students to consider the significance of the badge and other awards given for meritorious conduct in the war, its 1932 revival as the modern Purple Heart and George Washington’s conviction that in the new American republic, the “road to glory” was open to all.

Washington's Purple HeartThe Black Patriot

The Black Revolutionary War Patriots Act was signed into law in 1986 authorizing a physical memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., after which efforts to fund its design and construction began—including the sale of bronze prototype figures. In 2005, plans for a National Liberty Memorial, a “commemorative work to slaves and free black persons who served in the American Revolution” as “soldiers, sailors, marines, patriots and liberty seekers” replaced the original proposal, extending authorization for a memorial until 2021. This lesson invites students to consider the process public memorials undergo from inspiration to dedication.

COMING SOON

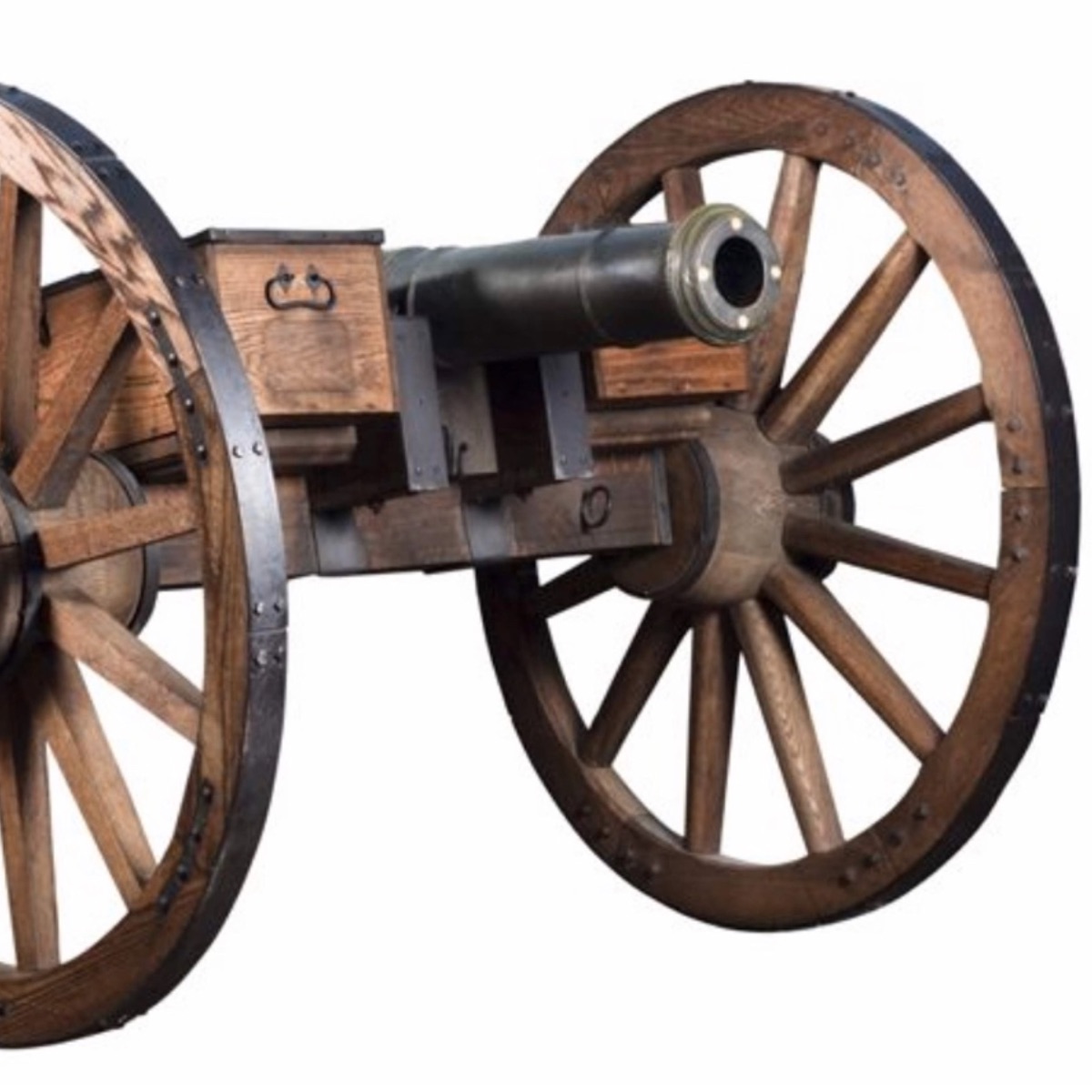

James Byers Six-Pounder Cannon

Six-pounder cannons were the most common field artillery of the Revolutionary War. In this lesson, we begin with a physical examination of the object—size and weight, materials, workmanship, markings and signs of use. We turn then to archival sources to understand how it was made. We then to consider how it worked—how it was loaded, primed and fired. Then we turn back to documentary sources to interpret this example, including the richly symbolic markings cast into the barrel. What does this cannon tells us about the American war effort?

COMING SOON