Among the most important objects surviving from the American Revolution is the original Great Seal of the United States, made in 1782 and now in the care of the Department of State. In the summer of 1776, the Continental Congress appointed a committee consisting of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams to devise a national seal symbolizing the independent United States. Congress rejected the committee’s proposal and rejected the proposals of a second committee in 1780 and a third one in 1782. Finally, Congress turned the challenge over to its secretary, Charles Thomson, who combined ideas from each committee with his own ideas to create the Great Seal of the United States, which was adopted by Congress on June 20, 1782 and remains unchanged today.

In this lesson, students learn how the Revolutionaries created the Great Seal and what the different symbols that make up the Great Seal mean, and will consider how those symbols have been used to represent our national identity since the Revolutionary generation.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle and High School

Recommended Time Frame

Two fifty-minute sessions

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will:

- learn why and how the Revolutionaries created the Great Seal of the United States;

- explore the meaning of the symbols that make up the Great Seal;

- consider how the Great Seal and its various symbols have been used as to represent our common national identity.

Materials and Resources

(in order of appearance)

- John Adams to Abigail Adams, August 14, 1776

- Great Seal of the United States obverse

- Great Seal of the United States reverse

- Pierre Eugene du Simitiere, proposed design for the Great Seal, 1776

- Francis Hopkinson, proposed design for the Great Seal, 1780

- William Barton, proposed design for the Great Seal, 1782

- Charles Thomson, proposed design for the Great Seal, 1782

- Great Seal die, 1782

- Great Seal painting, ca. 1785

- Benjamin Franklin to Sarah Bache, January 26, 1784

- Rowan LeCompte, Faith of the Hebrews, 1991

Background Knowledge

Students should understand the role of the Continental Congress before, during and immediately after the Revolutionary War, and be familiar with the contributions of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin to that body.

Sequence and Procedure

- Display the obverse and reverse of the Great Seal of the United States to the class. Ask students to individually answer the “What I Know” and “What I Want to Know” portions of a K-W-L chart (What I Know-What I Want to Know-What I Learned) chart relative to the Great Seal. Discuss student responses as a class, then further discussion by asking students to share their opinions about how different parts of the Great Seal represent America’s national identity.

- Invite students to research the history of the creation and adoption of the Great Seal of the United States—in particular, the design contributions of one of the three successive committees appointed by the Continental Congress between 1776 and 1782. A summary history which may be used to guide student work follows the final step of this Sequence and Procedure. Break the class into groups assigning each the role of one of the three Great Seal committees. Have students discuss the details of the design proposal, considering each symbol the committee chose to help define America’s unique identity to the world.

- Inform students they have been charged with the task of devising a “new” Great Seal design, which must receive final endorsement by the class as a whole. To begin, each student group must present the design elements put forward in the proposals of the committee they studied to the class, then, with the approval of their committee peers, students may introduce original design elements for the class to consider, presenting each idea with a visual graphic as well as its symbolic interpretation relative to American independence. Facilitate a discussion or debate about the elements of each design, then ask the members of the class to individually vote on the symbols to appear this new design.

- Invite students to fill out the final column of their K-W-L chart relative to the Great Seal— “What I Learned.”

Summary History of the Creation and Adoption of the Great Seal of the United States

Soon after the United States presented itself to the world as a sovereign nation with the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress tapped three members of its Declaration committee to formalize America’s unique national identity and highest ideals with a graphic design for a great seal. On July 4, 1776, Congress “Resolved, That Dr. Franklin, Mr. J. Adams and Mr. Jefferson, be a committee, to bring in a device for a seal for the United States of America.”

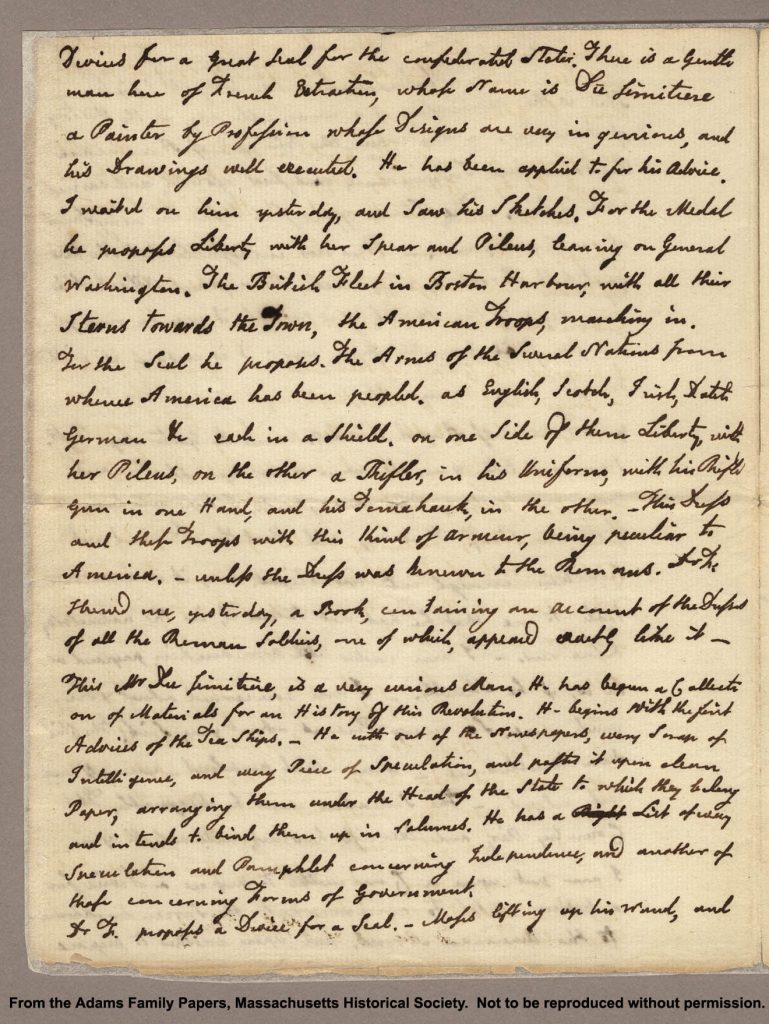

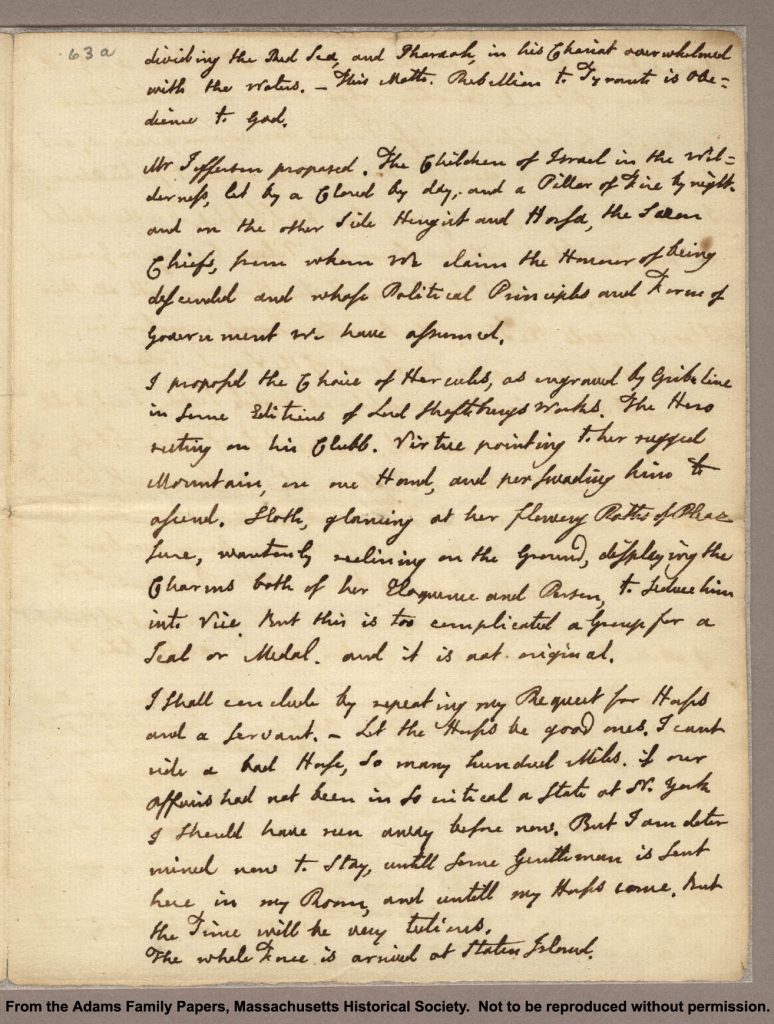

John Adams shared details about the committee’s work with his wife Abigail in an August 14 letter:

“Dr. F. proposes a Device for a Seal. Moses lifting up his Wand, and dividing the Red Sea, and Pharaoh, in his Chariot overwhelmed with the Waters. —This Motto. Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God. Mr. Jefferson proposed. The Children of Israel in the Wilderness, led by a Cloud by day, and a Pillar of Fire by night … I proposed the Choice of Hercules … resting on his Clubb.”

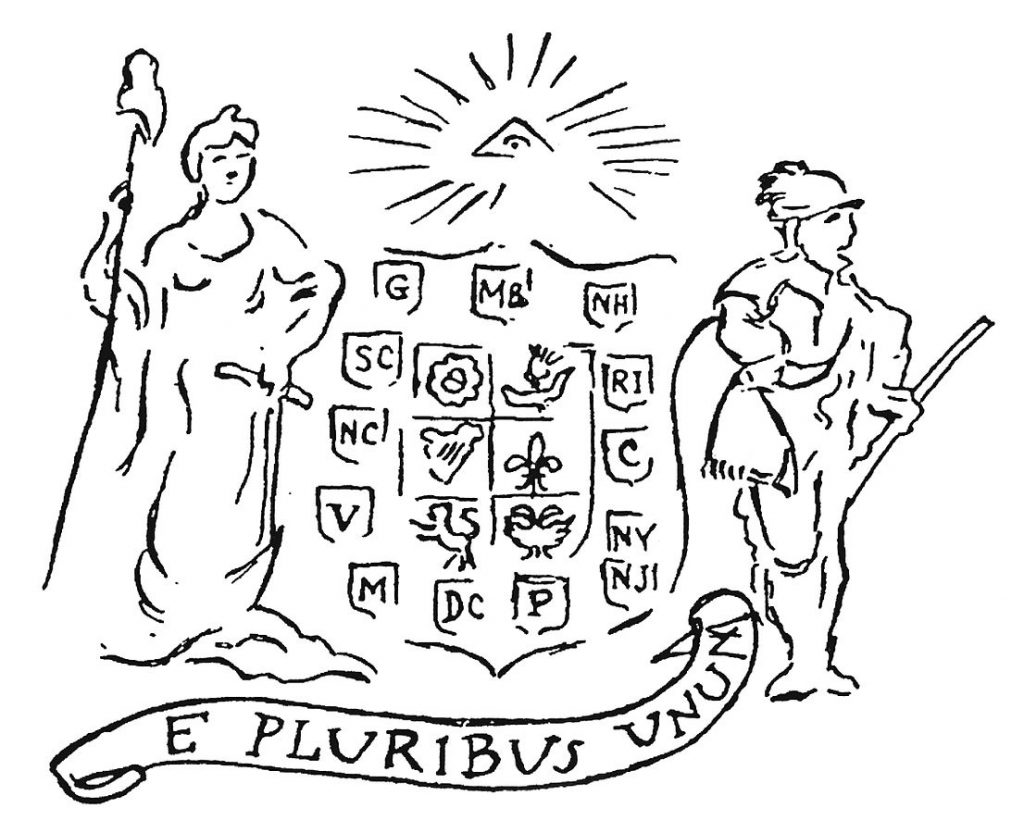

To bring their concepts to life, the group enlisted the support of portrait artist Pierre Eugene du Simitiere, who had some experience with heraldic design. Together they agreed on a design incorporating the Eye of Providence in a radiant triangle, the year 1776 expressed in Roman numerals, and a shield with the Latin motto E Pluribus Unum (out of many, one) emblazoned below it. After its submission on August 20, Congress allowed the design to “lie on the table.”

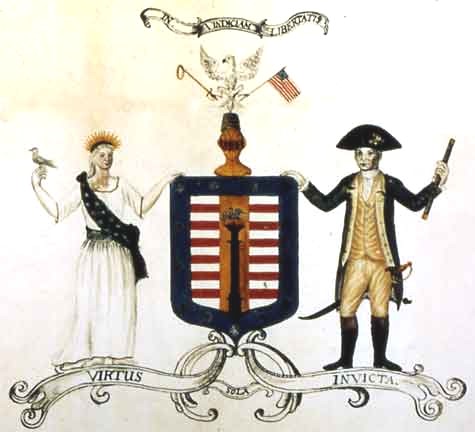

A second committee to consider the first committee’s work was commissioned in March 1780, comprised of James Lovell, John Morin Scott and William Churchill Houston. The men invited Francis Hopkinton—largely credited with the design of the American flag in 1777—to join them. While their finished work submitted in May of that year also failed to garner Congressional endorsement, this second committee’s design introduced some elements that were embraced—thirteen red and white stripes and a constellation of thirteen six-pointed stars to represent the original thirteen states, and an olive branch as a symbol of peace.

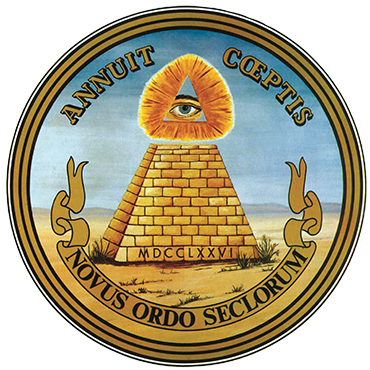

A third committee was appointed in May 1782 consisting of John Rutledge, Arthur Middleton and Elias Boudinot. Like its predecessors, this group incorporated the assistance of an outsider—William Barton, an artistically-gifted Philadelphia lawyer. After five days the group submitted its design, which featured a small imperial eagle holding an American flag in one talon and an unfinished thirteen-step pyramid capped by the Eye of Providence favored by the first committee. The design became the third to fail to win Congressional favor.

One month later—in June 1782—congressional secretary Charles Thomson submitted a great seal design which borrowed elements from all three committees. The central figure was an American bald eagle, adorned with a shield containing thirteen alternating red and white stripes, clutching an olive branch in its right talon and a bundle of arrows in its left, with a banner in its beak proclaiming E Pluribus Unum. A modified crest above the eagle’s head featured a constellation of thirteen stars surrounded by clouds. On the seal’s reverse, Thomson’s design included the unfinished pyramid topped by the Eye of Providence and the mottos Annuit Coeptis (God has favored our undertakings) and Novus Ordo Seclorum (a new order of the ages). William Barton, who assisted the third committee with its work, was employed to refine Thomson’s sketches. Barton tipped the eagle’s wings upward and imposed a blue rectangular chief at the top of the eagle’s shield of red and white vertical stripes. To reinforce the number of original states in the American union, Barton drew thirteen arrows in the eagle’s left talon. Thomson’s written description of this fourth great seal design was submitted on June 20 and adopted the same day. His “Remarks and Explanations” read:

“The Escutcheon is composed of the chief [upper part of shield] & pale [perpendicular band], the two most honorable ordinaries [figures of heraldry]. The Pieces, paly [alternating pales], represent the several states all joined in one solid compact entire, supporting a Chief, which unites the whole & represents Congress. The Motto alludes to this union. The pales in the arms are kept closely united by the Chief and the Chief depends on that union & the strength resulting from it for its support, to denote the Confederacy of the United States of America & the preservation of their union through Congress. “The colours of the pales are those used in the flag of the United States of America; White signifies purity and innocence, Red, hardiness & valour, and Blue, the colour of the Chief signifies vigilance, perseverance & justice. The Olive branch and arrows denote the power of peace & war which is exclusively vested in Congress. The Constellation denotes a new State taking its place and rank among other sovereign powers. The Escutcheon is born on the breast of an American Eagle without any other supporters [figures represented as holding up the shield] to denote that the United States of America ought to rely on their own Virtue. “Reverse. The pyramid signifies Strength and Duration: The Eye over it & the Motto allude to the many signal interpositions of providence in favour of the American cause. The date underneath is that of the Declaration of Independence and the words under it signify the beginning of the New American Era, which commences from that date.”

A brass die was cut, and on September 16, 1782, Thomson used the design for the first time on a document authorizing George Washington to negotiate a prisoner of war exchange between British and American troops.

Charles Thomson continued to serve as the official keeper of the Great Seal until the institution of America’s new republic under the United States Constitution, at which time custody of the seal passed to Thomas Jefferson, the United States’ first secretary of state. The United States Department of State remains the custodian of the seal today, using a modern die retaining the 1782 design specifications to impress the seal onto thousands of official government documents annually including treaties, commissions and appointments. The Great Seal design is used by other offices of the United States government on postage stamps, official documents, flags, uniforms, buildings, monuments, coins, and most notably, the one-dollar bill.

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

Ask students to individually redesign the Great Seal of the United States, incorporating at least three symbols to represent America’s national identity. Students should defend the symbols and iconography they choose to incorporate with a persuasive essay explaining how their design elements relate to America’s past and present.

Extension

Extension One

Thomas Jefferson’s idea for the design of the Great Seal was adopted by Washington National Cathedral in Rowan LeCompte’s Faith of the Hebrews (1991), one of the three stained glass windows representing the three branches of government established by the United States Constitution. To honor America’s executive branch, the multifoil at the top of the window contains an image of the White House. The four main lancets of the window together depict the Hebrew nation’s forty-year journey through the wilderness—following a pillar of clouds by day and a pillar of fire by night, led by Moses, then Joshua, to the promised land. The window symbolizes the faith a nation must place in its leader, and the trust we invest in our American president.

Ask students to design a stained-glass window or mural incorporating allegory and iconography to represent one or more of the branches of American government.

Extension Two

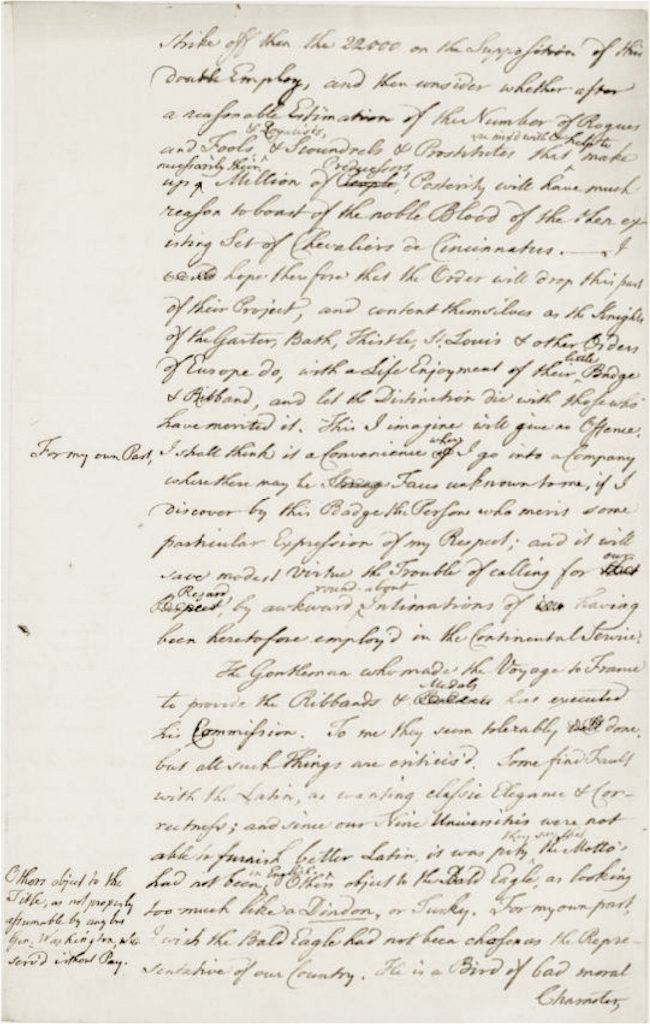

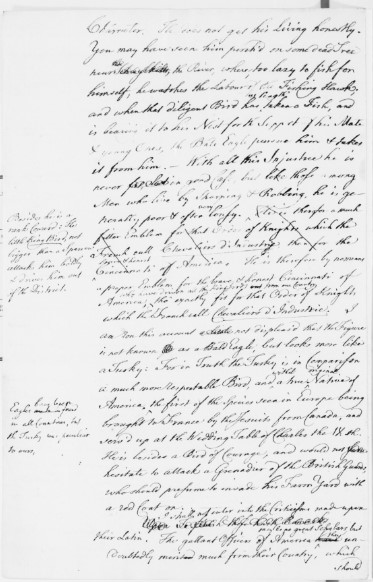

Benjamin Franklin, ambassador to France from December 1776 to May 1785, learned about the creation of Society of the Cincinnati after word traveled to him through French and American diplomatic and social circles following the war. The Society took its name from the ancient Roman hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus who was celebrated for refusing public reward or office after leading the Roman Republic to military victory—instead, returning to his modest life as a citizen-farmer. Writing from his residence outside Paris, Franklin penned a satirical letter responding to the Society’s establishment on January 26, 1784. The letter, which was not made public in Franklin’s lifetime, paid particular attention to the selection of the bald eagle as the national symbol of the United States and as the symbol embraced by the Society of the Cincinnati. Franklin wrote:

“Others object to the bald eagle, as looking too much like a Dindon or turkey. For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character. . . He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the king birds from our country, . . . For in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours, the first of the species seen in Europe being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding table of Charles the ninth. He is besides, (though a little vain and silly tis true, but not the worse emblem for that) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.”

Have students compare the eagles in Charles Thomson’s great seal design, the 1782 Great Seal die, and the 1785 Great Seal painting in St. John’s Chapel at Trinity Church in New York City, noting the look of these birds as compared to the eagle appearing on the official obverse of the Great Seal of the United States. Reflecting on Franklin’s comments, ask students to pen a letter responding to Benjamin Franklin on the subject of choice of a bald eagle as the central figure on the Great Seal of the United States. Students might note how the distinctive composition of early eagle designs reflect a wilder-looking American bird—perhaps even a wild turkey.

Revolutionary Achievements Category

National Identity

Exploring the Revolution Category

The Revolutionary Republic, The Legacy of the Revolution

Great Seal of the United States obverse

U.S. Department of State

The most prominent feature is the American bald eagle supporting the shield, or escutcheon, which is composed of thirteen red and white stripes,representing the original states, and a blue top which unites the shield and represents Congress. The motto, E Pluribus Unum (out of many, one), alludes to this union. The olive branch and thirteen arrows denote the power of peace and war, which is exclusively vested in Congress. The constellation of stars denotes a new State taking its place and rank among other sovereign powers.

Great Seal of the United States reverse

U.S. Department of State

The pyramid signifies strength and duration. The eye over it and the motto, Annuit Coeptis (He [God] has favored our undertakings), allude to the many interventions of Providence in favor of the American cause. The date in Roman numerals underneath is that of the Declaration of Independence, and the words under it, Novus Ordo Seclorum (a new order of the ages), signify the beginning of the new American era in 1776.

John Adams to Abigail Adams

August 14, 1776Massachusetts Historical Society

“dividing the Red Sea, and Pharaoh, in his Chariot overwhelmed with the Waters.—This Motto. Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God. Mr. Jefferson proposed. The Children of Israel in the Wilderness, led by a Cloud by day, and a Pillar of Fire by night…I proposed the Choice of Hercules...resting on his Clubb.”

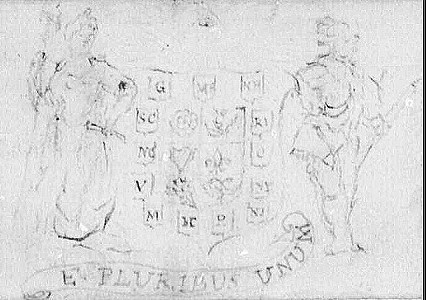

Great Seal design

Pierre Eugene du Simitiere

1776Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress

Pierre Eugene du Simitiere's sketch for the Great Seal of the United States was drafted during the first committee's proceedings in 1776. Six years later, the E Pluribus Unum motto was used on the final seal, and the Eye of Providence was an element on the reverse. This design is apparently the origin of both, as far as their usage by the U.S. Government.The seal depicts a shield with six regions, representing the "Countries from which these States have been peopled" (Rose for England, Thistle for Scotland, Harp for Ireland, Fleur-de-lis for France, Belgic Lion for the Netherlands--then the Dutch Republic--and an Imperial Eagle for Germany) surrounded by the initials of all thirteen states. The Goddess of Liberty is on the left (the shield's right, or dexter), and the Goddess of Justice is on the other side.

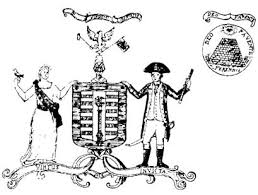

Great Seal design

Francis Hopkinson

1780U.S. Diplomacy Center (State Department)

The obverse side of Francis Hopkinson's design for the Great Seal of the United States, done as part of the second committee (of three) to attempt a design. This was not used, though some elements (the constellation of stars surrounded by clouds, the olive branch, the thirteen red and white stripes on the shield, and the general theme of peace and war) were used in the final design.The description in the committee's final report was: "The Shield charged on the Field Azure with 13 diagonal stripes alternate rouge and argent— Supporters; dexter, a Warriour holding a Sword; sinister, a Figure representing Peace bearing an Olive Branch— The Crest— a radiant Constellation of 13 Stars— The motto, Bella vel Paci. (for war or for peace)."

This was a modification of a design made by Hopkinson a few days previously, where the warrior was depicted as an American Indian with a bow and arrow.

Extracted from PDF version of Creating the Great Seal poster, part of a U.S. Diplomacy Center (State Department) exhibition on the 225th anniversary of the Great Seal.

Great Seal design

William Barton

1782U.S. Department of State

Known as a "blazon," the following report was submitted to Congress on May 9, 1782 by the third Great Seal committee:Arms.

Barry of thirteen pieces, Argent & Gules; on a pale, Or, a Pillar of the Doric Order, Vert, reaching from the Base of the Escutcheon to the Honor point; and, from the Summit thereof, a Phoenix in Flames with Wings expanded, proper: the whole within a Border, Azure, charged with As many Stars as pieces barways, of the first.

Crest.

On an Helmet of Burnished Gold, damasked, grated with six Bars, a Cap of Liberty, Vert; with an Eagle displayed, Argent, resting thereon; holding in his dexter Talon a Sword, Or, having a Wreath of Laurel suspended from the point; and, in the sinister, the Ensign of the United States, proper.

Supporters.

On the dexter side, the Genius of the American Confederated Republic: represented by a Maiden, with flowing Auburn Tresses; clad in a long, loose, white Garment, bordered with Green; having a Sky blue Scarf, charged with Stars as in the Arms, reaching across her Waist from her right Shoulder to her left Side; and, on her Head, a radiated Crown of Gold, encircled with an Azure Fillet spangled with Silver Stars: round her Waist a Purple Girdle, embroidered with the Word "Virtus," in Silver a Dove, proper, perched on her dexter Hand.

On the sinister side, an American Warrior; clad in a uniform Coat, of blue faced with Buff, and in his Hat a Cockade of black and white Ribbons: in his left Hand, a Baton Azure, semé of Stars Argent.

Motto, over the Crest – "In Vindiciam Libertatis."

Motto, under the Arms – "Virtus sola invicta."

Barton's reverse of Great SealReverse of the Seal.

A Pyramid of thirteen Strata, (or Steps) Or, and, on the Summit of it a Palm Tree, proper. In the Zenith, an Eye, surrounded with a Glory, proper.

In a Scroll, above, or in the Margin – "Deo Favente."

The Exergue – "Perennis."

Great Seal die

1782National Archives

The first die was cut from brass in 1782 by an engraver who has not beenpositively identified (possibly Robert Scot of Philadelphia) and is now on public display in the National Archives. It measures 2 5/16 inches in diameter and carries a relatively crude rendering of a crested eagle, its head protruding into the constellation of six-pointed stars. The bundle of thirteen arrows and the olive branch, bare of fruit, are pressed against the border of modified acanthus leaves. The eagle on the Great Seal has always faced to its own right. The eagle that faced to its own left (toward the arrows) was in the Presidential seal until President Truman altered the design in 1945, ordering that the eagle’s head be turned toward the olive branch.

Benjamin Franklin to Sarah Bache

January 26, 1784Library of Congress

“Others object to the bald eagle, as looking too much like a Dindon or turkey. For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character,”

Benjamin Franklin to Sarah Bache

January 26, 1784Library of Congress

“He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the king birds from our country,...For in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours, the first of the species seen in Europe being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding table of Charles the ninth. He is besides, (though a little vain and silly tis true, but not the worse emblem for that) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.”

Faith of the Hebrews

Rowan LeCompte

1991Washington National Cathedral

This is the second of the windows donated by Hugh Trumbull Adams in honor of the three branches of government, this one the executive branch. One of the most striking images in the window is that of the long column of human figures led by Moses that begins at the top of the left lancet, proceeds downwards and across the bottom of all four lancets, and then upward in the right lancet. This procession reflects the window's theme of the persistent faith of the Hebrew nation during its forty-year journey through the desert, as well as the faith America places in the leadership of its president. LeCompte chose to represent the concept of faith with a mighty, red pillar of fire in the left center lancet and a glorious, blue and yellow pillar of clouds in the right center lancet, as described in the biblical accounts, where the Hebrews were led by a pillar of clouds by day and a pillar of fire by night. In the multifoil is an image of the White House. The inscription at the base of the window is from the second part of the opening sentence of the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution: "in Order to form a more perfect Union."