American independence was won by men who refused to be beaten—who were defeated and rose again, battered but determined. That’s the lesson we can learn from the battlefield of Camden and from the story of Thomas Pinckney, a remarkable young man who embodied the courage it took to win our independence.

You can walk the battlefield of Camden, now preserved by the Historic Camden Foundation, in less than an hour. That’s longer than the battle took to fight. An American army of about four thousand men—a mix of Continental Army regulars and Virginia and North Carolina militia—confronted an army of British regulars and loyalists there on August 16, 1780.

The Revolutionary War was then in its sixth year. The British had largely given up on conquering their former colonies to the north, but they were intent on recovering Georgia and the Carolinas, and if things went their way, Virginia and Maryland, too. In the late summer of 1780 things were going very much their way. They had occupied Savannah and taken Charleston, and in the process had taken most of the Continental Army in the South prisoner.

In August a British army under Lord Cornwallis was marching through the South Carolina interior, mopping up resistance and preparing to invade North Carolina, when a hastily assembled patriot army barred their path in the pine forest north of Camden.

The battle began shortly after first light, the heavy smoke of cannon fire hanging in the trees, covering the battlefield in a thick fog. As the British advanced, the Continentals on the right swung out to meet them. The British got the worst of the first exchange, but on the American left, Virginia militia fled at the sight of British bayonets bearing down on them through the battle smoke. Their left flank exposed, most of the North Carolina militia followed the Virginians pell-mell off the battlefield.

On the American right, though it was only a few hundred yards away, Continental officers could not see what had happened. Continentals exchanged fire with the British regulars at short range, both sides taking a severe beating before the Americans—outflanked and outnumbered—were overwhelmed.

Over nine hundred Americans were killed or wounded that day, among them twenty-nine-year-old Major Thomas Pinckney. A British musket ball smashed his thigh, causing a compound fracture. The fragment of the American army that managed to escape the battlefield left him behind. He was taken prisoner, though in such anguish that his captors cannot have expected him to trouble them long. They released him on parole to relatives, who cared for him as best they could. Doctors saved his leg—an extraordinary thing—though Pinckney endured enormous pain.

Less than a year later, Pinckney had recovered sufficiently to mount a horse, which was enough for him to return to duty as an aide to the marquis de Lafayette, who was sparring with Cornwallis in Virginia. Ultimately Cornwallis withdrew to the tidewater village of Yorktown to rest and wait for support that never arrived. A few weeks later Thomas Pinckney had the pleasure of watching Cornwallis and his British army—the victors at Camden—surrender their arms.

Too often we neglect the very real people, like Thomas Pinckney, who suffered to secure our independence. Pinckney came from a wealthy family. He had little to gain—at least personally—and most everything to lose by fighting the British in what many perceptive people believed was an utterly hopeless cause. If Pinckney had nursed his shattered leg and remained at home, rather than return to service as he did, who could have blamed him?

The answer is that he would have blamed himself. He had joined the Continental Army in 1776 and had committed himself, like many others about whom we know much less, to a cause greater than himself. And so he mounted a horse and returned to war, and saw that war through to an improbable victory.

He went on to a remarkable career in public life, as governor of South Carolina, ambassador to Britain and an emissary to Spain who negotiated the treaty that opened the Mississippi River to American commerce—without which the vast region west of the Appalachians might have drifted away, and what became the United States might have become an array of smaller countries.

We neglect men like Thomas Pinckney when we reduce historical analysis to abstractions of class or wealth or region or to numbers on a ledger, forgetting that so much of history is contingent on the decisions very real men and women make and the actions they take. The remarkable Thomas Pinckney—climbing back into the saddle months after a devastating defeat—reminds us to honor them as individuals who endured hardships, suffered anguish and defeat, and persevered.

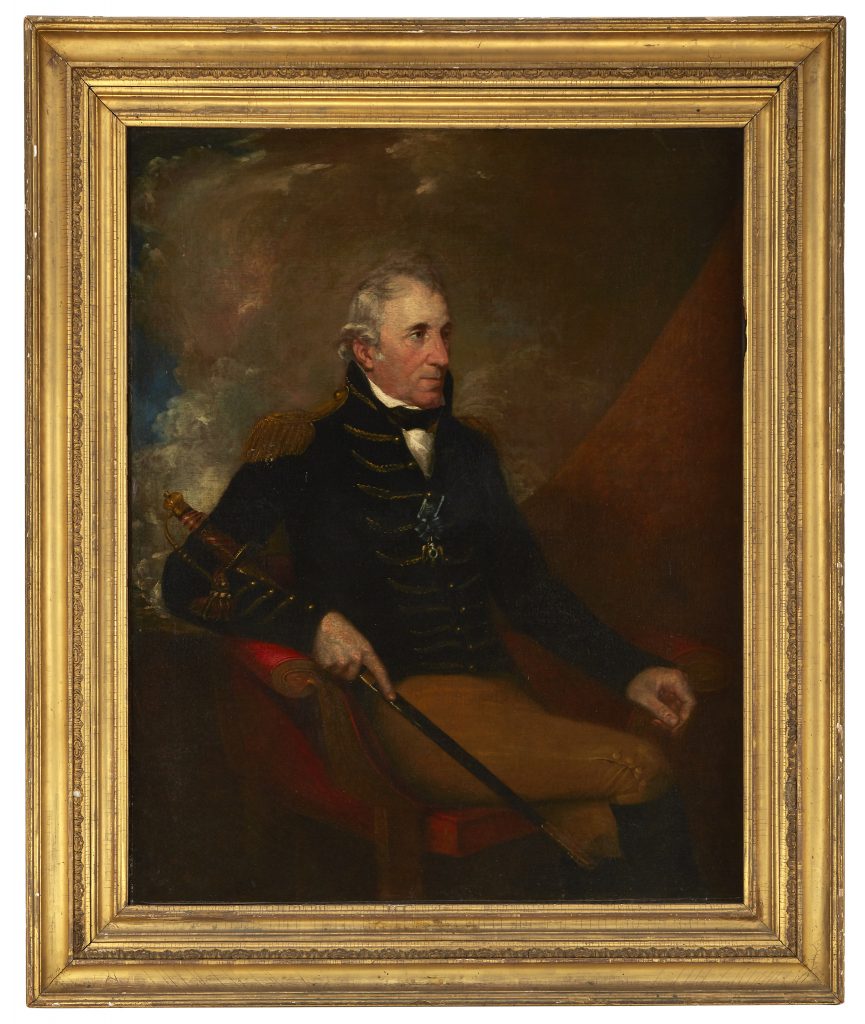

Learn about our project to conserve Samuel F.B. Morse’s equally remarkable Thomas Pinckney portrait, which is now a part of the Institute’s museum collections.

Learn more about the preservation of the Camden battlefield, where Thomas Pinckney was wounded, from the Historic Camden Foundation.