To win their independence, Americans had to create an effective artillery service able to challenge the British on the battlefield. They had to secure cannon barrels, gun carriages, limbers, ammunition wagons and a wide array of other specialized equipment. They had to create a system to maintain that equipment. They had to obtain a steady supply of gunpowder and artillery projectiles. And they had to recruit and train men to serve the guns effectively.

They had to do all of this with little experience or preparation, while fighting a war with a major European power with a well-trained professional army, the world’s largest navy, factories to manufacture munitions, craft facilities to build and maintain equipment, and a well-established system for recruiting and training artillerists.

Creating an effective American artillery service was the work of many people. They were led by one extraordinary young man. Henry Knox left school at twelve and went to work as a clerk in a bookstore to support himself and his mother. In 1771, at the age of twenty-one, he opened his own bookstore. He studied the military books he sold in his shop, joined a militia company and managed to shoot two fingers off his left hand at the age of twenty-three. Shortly after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Knox slipped out of Boston with his young wife, Lucy, and joined the militia army surrounding the city. With the knowledge he had extracted from books, Knox designed and oversaw the construction of patriot fortifications. The twenty-five-year-old Knox soon came to the attention of George Washington, the forty-two-year-old, newly appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. They quickly formed one of the most important partnerships of the American Revolution.

Boom! Artillery in the American Revolution traced the development of the Continental Artillery during the Revolutionary War, a process shaped by broader technological and organizational changes in artillery that transformed it into a dominant force on European and American war battlefields. The artifacts, books, maps, manuscripts and other objects in the exhibition were drawn from the collections of the Society of the Cincinnati, most importantly from the Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection, which documents the art of war in the eighteenth century.

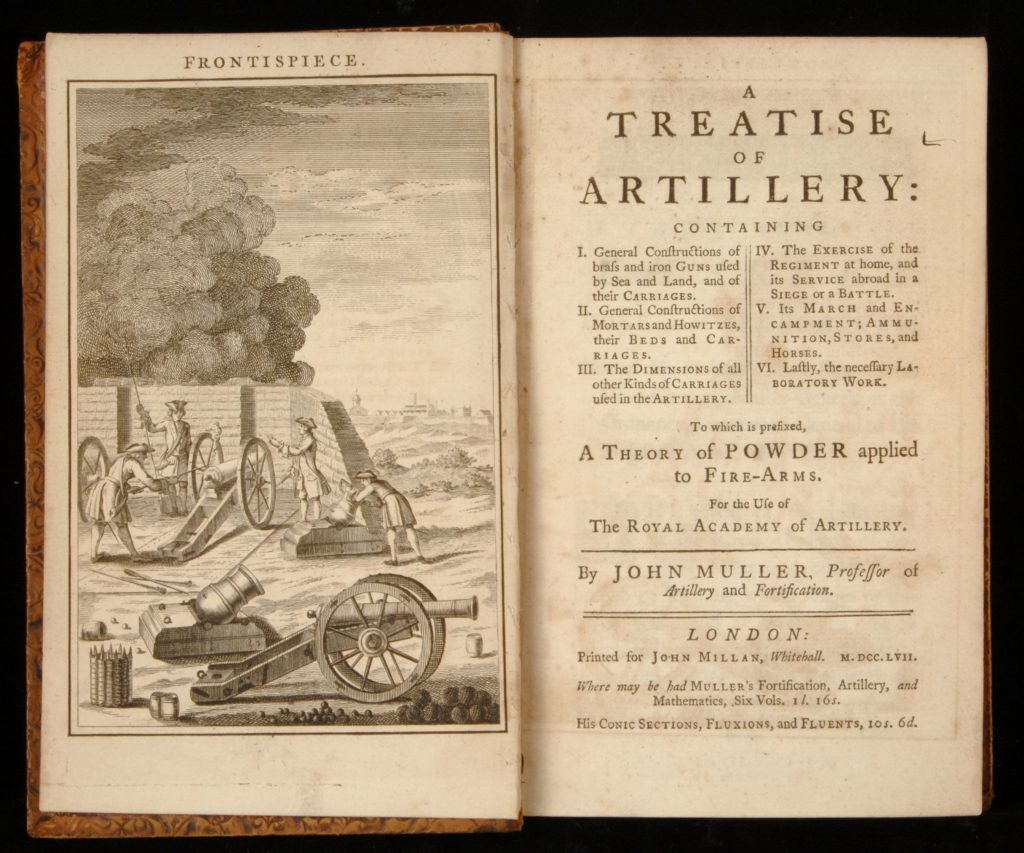

A Treatise of Artillery

John Muller

London: John Millan, 1757The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

John Muller (1699-1784), long-time headmaster of the Woolwich academy, Britain’s school for artillery, was the author of A Treatise of Artillery, the most influential work on artillery in English during the second half of the eighteenth century. George Washington owned the first edition, published in 1757. Henry Knox studied and sold the second edition, published in 1768, in his Boston book store. Dozens of American artillery officers read and studied Muller’s Treatise. American craftsmen used the detailed plates as plans for constructing gun carriages, mortar beds, limbers, ammunition wagons and other supporting equipment.

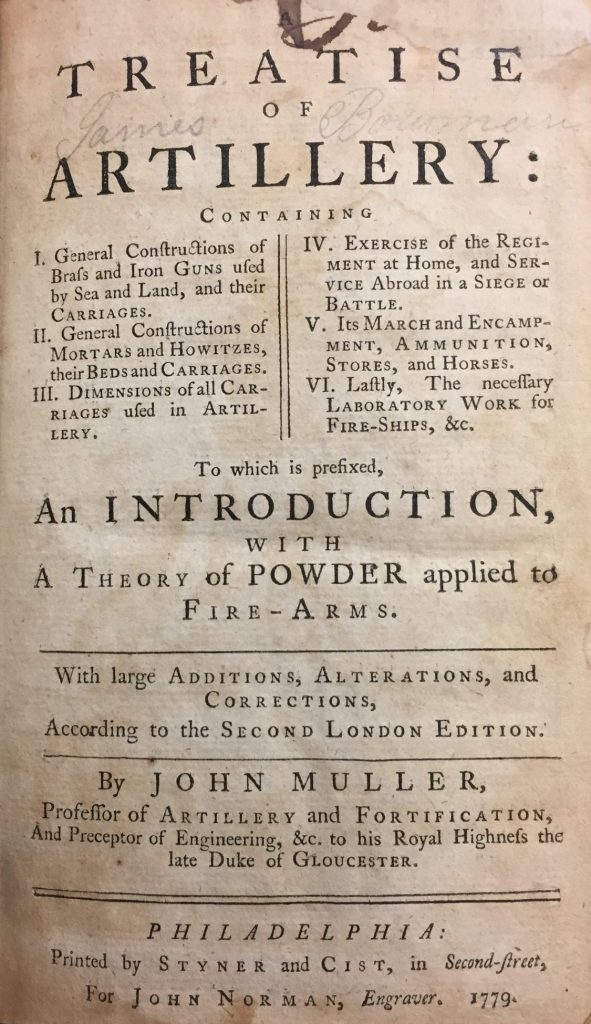

A Treatise of Artillery

John Muller

Philadelphia: John Norman, 1779The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

“The officers of the army are very difficient in Books upon the military art,” Henry Knox wrote to John Adams on May 16, 1776, adding that this “does not arise from their disinclination to read but the impossibility of procuring the Books in America.” He recommended Muller’s Treatise of Artillery as a book “necessary for a people struggling for Liberty and Empire.” This American edition of Muller’s Treatise was published in Philadelphia in 1779, with a frontispiece and twenty-eight folding plates copied from an earlier edition.

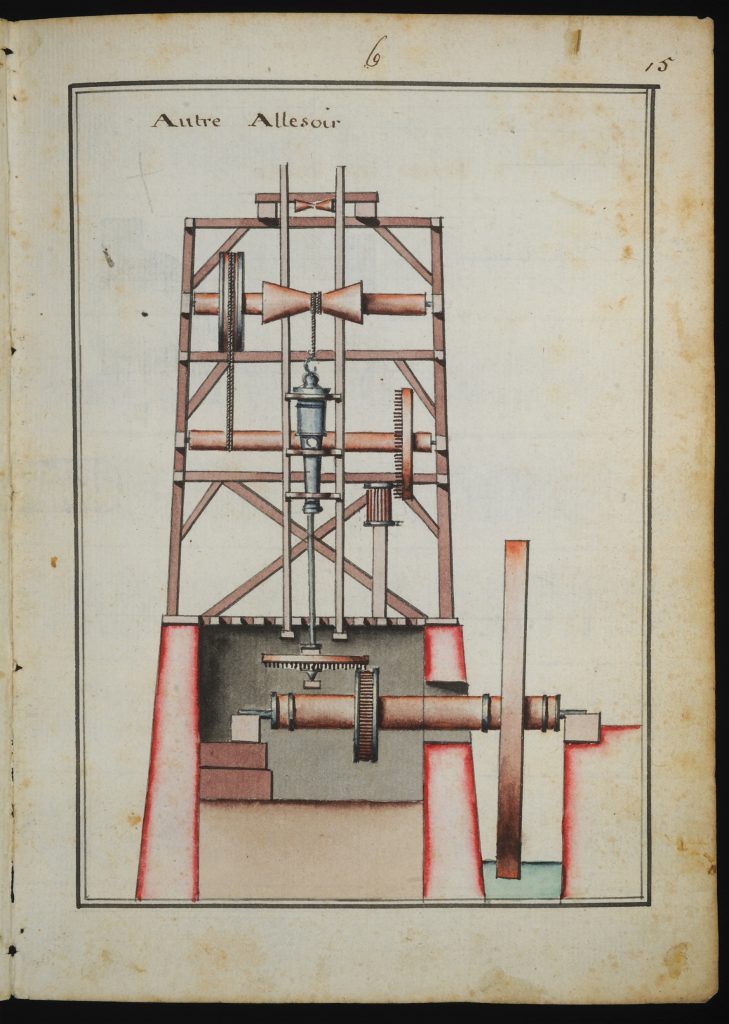

Vertical boring mechanism

Jean Alexandre, baron d’Espiard de Colonge

“Figures de l’Artillerie Pratique,” Volume 2Mid-eighteenth century

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

This drawing of a mechanism for drilling cannon barrels to create a perfectly straight bore comes from a unique volume of watercolors painted in France in the mid-eighteenth century. This elaborate machine lowered a solid casting on to a turning drill. Drilling—whether by this method or, later, by horizontal drilling—made cannon bores more precise and reduced the amount of gunpowder needed. The cannons used in the American War for Independence were produced using this revolutionary technology.

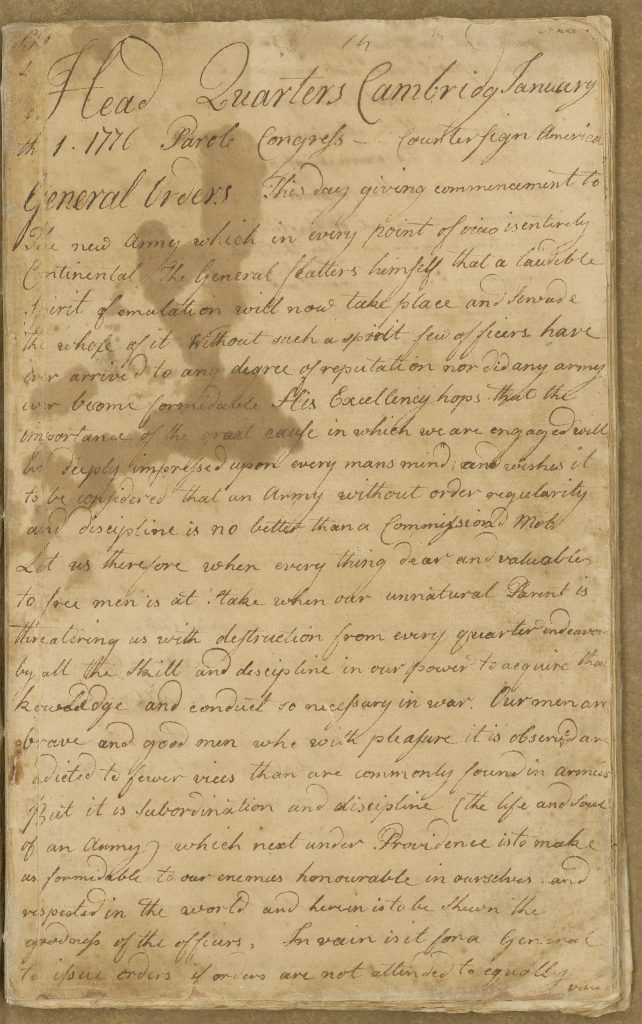

Orderly Book of the Continental Army Artillery Regiment

Kept by Gershom Foster

January 1 – February 24, 1776The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Gershom Foster of Middleborough, Massachusetts, kept this orderly book, which documents the changes in the Continental Artillery imposed by Henry Knox in the winter of 1776. Foster recorded that, on January 28, 1776, Knox issued his first regimental orders: “It is of the utmost Importance that the Regt. Of Artillary in the Service of the United Colonies Should be well Regulated & well disciplined.” Knox drilled his men constantly, laying the foundations of an effective American artillery service.![Click for a larger view. Attaque de l’armée des provinciaux dans Long Island du 27. aoust 1776, Georges-Louis Le Rouge, cartographer, London and Paris: Chez le Rouge, [1777]](https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Attaque-de-larmée-MAP-L2012F52f-932x1024.jpg)

Attaque de l’armée des provinciaux dans Long Island du 27. aoust 1776

Georges-Louis Le Rouge, cartographer

London and Paris: Chez le Rouge, [1777]The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The Continental Artillery commanded by Henry Knox on the eve of the British attack on New York City consisted of as many as 120 cannons and a force of some 520 officers and men. Effective artillery was essential to the defense of Manhattan, an island surrounded by a maze of waterways easily commanded by the powerful guns of the Royal Navy, as this contemporary French map suggests. The Continental Army lost the majority of its cannons, artillery ammunition and supporting equipment around New York City between August and November 1776. Knox’s frustration was enormous, but so was his determination to build an effective artillery service.

Solid shot

18th centuryThe Society of the Cincinnati, Acquired by gifts and purchases, 1975-2016

The Continental Artillery benefitted from increasing production of projectiles by private iron furnaces during 1777, as ironmasters acquired the technical knowledge to cast reliable shot and shell. These examples were found (left to right) at Brandywine, Fort Ticonderoga, on the banks of Assunpink Creek near Trenton, and at Saratoga. The shot from Ticonderoga bears a broad arrow, indicating British manufacture.

Benjamin Flower

Unidentified American artist

ca. 1778-1780The Society of the Cincinnati, Museum Acquisition Fund purchase, 2014

On January 16, 1777, George Washington appointed Lt. Col. Benjamin Flower (1748-1781) commissary of military stores and directed him to manage the Philadelphia artillery yard and set up the arsenal at Carlisle. Flower organized operations in Philadelphia, which included a brass foundry to cast cannon barrels, and oversaw the construction of the arsenal at Carlisle. He is depicted here in the uniform of the Continental Artillery. Flower was an energetic organizer, but his work was slowed by chronic illness—probably tuberculosis. He died at the age of thirty-three.

Grapeshot

French

18th centuryThe Society of the Cincinnati, Museum purchase, 2016

Grapeshot like this one recovered at Monmouth was a specialized projectile used to repulse infantry at close range. This grapeshot was excavated just east of a hedgerow behind which American troops sheltered to slow the initial British pursuit. It may have been fired by one of two American guns posted to defend the position, which was attacked by British dragoons and then by grenadiers, who overran the American line. A British grenadier remembered that he faced “the Rebel’s cannon playing Grape and Case upon us at a distance of 40 yards.”

Methods for Fabricating Ordnance

ca. 1799The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

A round of grapeshot consisted of a cluster of iron balls packed around a wooden rod fixed to a round wooden base (a tampion) and covered with cloth stitched to hold the balls together in a tight bundle like a cluster of grapes. Tampion and cloth disintegrated when a round of grapeshot was fired, and the balls blew out of the cannon like a shotgun blast. Like case shot, grapeshot was brutally effective against attacking infantry at one hundred yards or less.

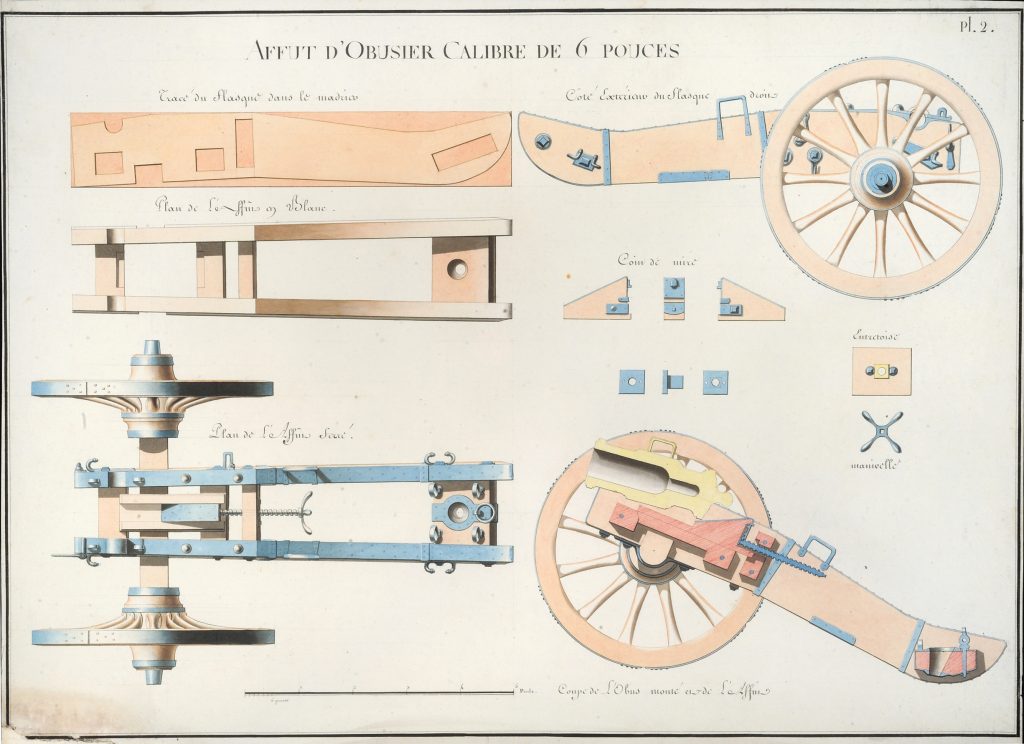

“Affut D’Obusier Calibre de 6 Pouces”

ca. 1780The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

In 1765 the French army adopted a comprehensive system of standardized guns and equipment developed by Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval (1715-1789). The Gribeauval system took advantage of improved foundry techniques and horizontal boring to make lighter field guns, and carefully specified the design of carriages, limbers, ammunition wagons, all of the associated equipment and a complete catalog of interchangeable parts for every component. This watercolor-and-ink diagram illustrates the carriage of a Gribeauval six-inch howitzer, a versatile, mobile weapon used in the field as well as in siege work. Guns like this one arrived with Rochambeau’s army in 1780.

Plan of the Investment of York and Gloucester

Sebastian Bauman, cartographer

Philadelphia: Engraved and Printed by Robert Scot, 1782The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The Siege of Yorktown gave American artillerists their greatest opportunity to demonstrate their hard-won proficiency. This extraordinarily detailed map of the siege was the work of Maj. Sebastian Bauman (1739-1803) of the Second Continental Artillery. Bauman commanded a battery during the siege and participated in receiving the British surrender on October 19. His map depicts the lines of fire that French and American artillerists used to compel the surrender.