Interpreting the Visual Record

Imagining the Revolution is a series of lessons that challenge students to consider works of art depicting events of the American Revolution as primary sources—not for the events they depict, but for understanding how artists and their audiences have thought about those events. The goal of the series is to enrich understanding of the American Revolution and its important role in American culture, while teaching students to interpret visual images as historical evidence.

The lessons in the series ask students to set aside the most common question asked about any work of art depicting an historical event: Is it accurate? They challenge students to ask more sophisticated questions: Why did the artist depict the event as he did? What does the work of art suggest the artist and his generation thought about the event and the people involved in it?

Imagining the Revolution leads students to consider visual arts in the same way we ask them to consider letters, speeches and other documents. When students read Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, their first question should not be whether King was right. Their first question should be about why King wrote what he wrote, and what he hoped to achieve. When they consider works of art as historical artifacts, students should ask what the artist was trying to convey and why.

Each lesson in Imagining the Revolution is based on a work of art. Some present more than one, often inviting comparison between images and asking students to consider how and why the images differ. Some of the lessons focus on images created in the revolutionary era. Others focus on images created long after the American Revolution, but which reflect the central importance of the American Revolution in American culture.

A central premise of Imagining the Revolution is that the American Revolution created our national identity. That identity was shaped and defined by visual images of the Revolution. Some of those images, like John Trumbull’s depiction of the Battle of Bunker Hill and Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, have been reproduced hundreds and even thousands of times, and are fundamental parts of our shared national culture.

The aim of Imagining the Revolution is to teach students how to interpret the visual record of the American Revolution, which consists of visual arts—paintings, drawings, prints, and sculpture. The American Revolution took place before photography made it possible to create literal depictions of people and events. The visual record of the American Revolution consists of images filtered by the imagination of their creators, and usually created to shape the impressions of viewers about people and events. Imagining the Revolution asks students to go beyond the obvious questions about the literal accuracy of images to explore the intent of the artists and the meaning they and their contemporaries attached to the people and events they depicted. Today’s students are bombarded with images, and the ability to interpret them properly is a skill of ever increasing importance.

Imagining the Boston Massacre

This lesson invites students to examine and interpret depictions of the fatal confrontation between Bostonians and British soldiers on the night of March 5, 1770, including engravings published within weeks of the tragedy. The lesson challenges students to set aside preconceptions about the images, examine them in detail, and reach interpretive conclusions about how the images reflect what the artists and their audiences thought about the event.

Imagining the Boston Massacre

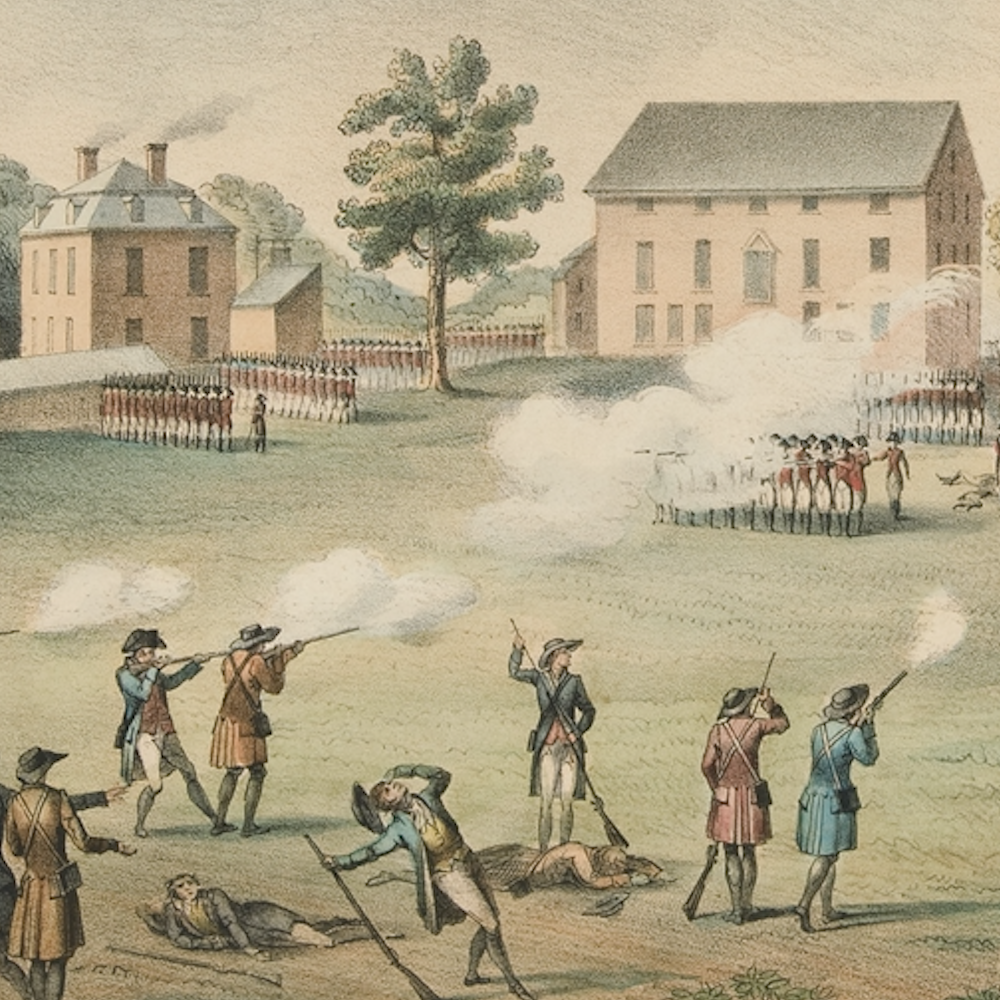

Imagining the Battle of Lexington

This lesson invites students to consider four different published images of the Battle of Lexington, created over 123 years beginning with one created in the summer of 1775. In the first image, Lexington militiamen are presented as victims, but in each of the succeeding images they are depicted returning British fire with increasing determination. The lesson asks students to consider why the depictions changed over time.

Imagining Lexington

Imagining the Battle of Bunker Hill

This lesson invites students to consider two contemporary images of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first created in the summer of 1775 as a response to popular interest in the battle, and the second the familiar John Trumbull painting executed shortly after the war. The lessons asks students to compare the two and suggest why the artists chose to emphasize different aspects of the battle.

Imagining the Battle of Princeton

This lesson asks students to analyze and compare two very different depictions of the Battle of Princeton created by contemporaries. The first image is James Peale’s painting, The Battle of Princeton. Peale’s Princeton is uniquely important, because it is the only painting of a Revolutionary War battle painted by a participant. The second is John Trumbull’s The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777.

Imagining Princeton

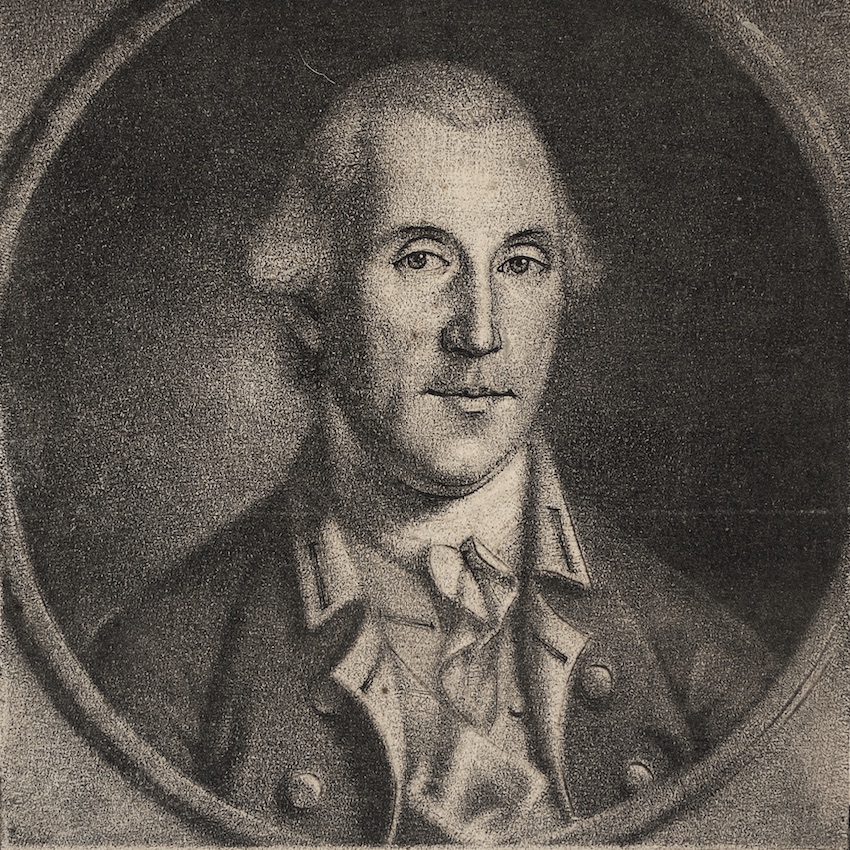

Imagining George Washington

This lesson asks students to examine three contemporary images of George Washington and consider what the artist was seeking to convey about Washington in each. The aim of the lesson is to train students to look for symbolic elements in otherwise familiar images.

Imagining Washington

Imagining the Swamp Fox

Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of South Carolina, became one of the most important heroes of the Revolutionary War in the early nineteenth century, thanks largely to popular books, poems, and paintings that were published as prints sold all over the country. This lesson asks students to consider how images are shaped by popular literature and in turn shape the way Americans think about their past.

Imagining the Swamp Fox

Imagining the Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown and the subsequent surrender of the British army under Lord Cornwallis was the climactic victory of the Revolutionary War on the North American mainland. This lesson asks students to consider two great depictions of the event—John Trumbull’s heroic painting of the surrender displayed in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, and August Couder’s equally heroic painting of the siege displayed in the Hall of Battles in the Palace of Versailles in France—and analyze why the artists chose to depict the event as they did.

COMING SOON

Imagining the Abolition of Slavery

In 1792, Samuel Jennings, a native of Philadelphia living in England, painted an allegory symbolizing the abolition of slavery for the reading room of the Library Company of Philadelphia, the oldest private library in the United States and a center of antislavery thought and action. This lesson challenges students to interpret the rich symbolism in the painting to reveal what the painting meant to the directors of the Library Company who instructed Jennings, and more broadly about how they imagined slavery should be ended.

Imagining Abolition