The long struggle for women’s rights began in the American Revolution, with the assertion of universal natural rights. Women were active in the struggle for American independence and supported the high ideals of the Revolution, despite the fact that they were not afforded the same political rights as men. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century suffragists appealed to the ideals of the Revolution in their struggle to secure the vote for women, culminating in the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. This lesson highlights the experience of women in the American Revolution and ways the ideals of the Revolution shaped the struggle for women’s political rights.

Abigail Adams, portrayed here by Benjamin Blyth around 1766, was a perceptive commentator on the American Revolution and an early advocate for women’s rights (Massachusetts Historical Society).

Suggested Grade Level

Middle and High School

Recommended Time Frame

One or two fifty-minute sessions

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will learn:

- how eighteenth-century women, inspired by the Revolution’s high ideals, influenced the women’s suffrage movement, and

- how the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, civic responsibility and natural and civil rights shaped the struggle for women’s rights in the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Materials and Resources

(in order of appearance)

- Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 31, 1776

- Rachel Nellis, Deborah Sampson at War, May 15, 2020

- Carol Berkin, Women Who Followed the Continental Army, Part 3 of 5: Molly Pitcher: Women as Combatants, April 10, 2014

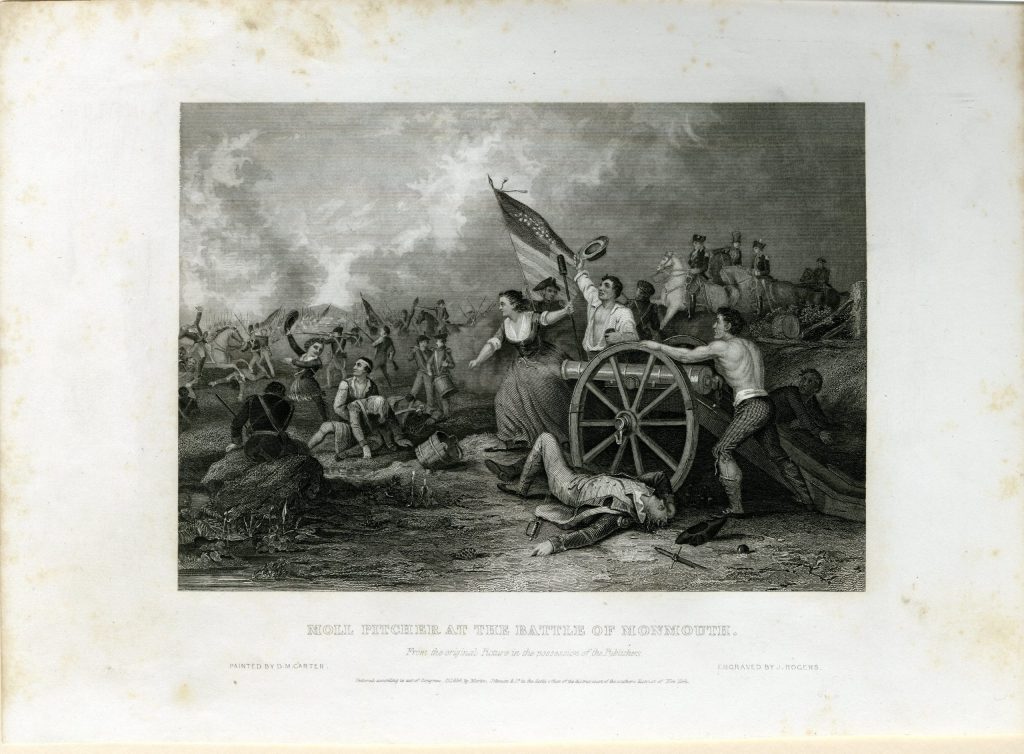

- D. M. Carter, artist, and John Roger, engraver, Moll Pitcher at the Battle of Monmouth, 1856 [see the gallery below]

- Margaret Corbin, Revolutionary essay

- Felix Darley, artist, and Charles Regnier, engraver, Nancy Hart (Georgia), 1853

- New Jersey State Constitution, July 2, 1776

- Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

- Declaration of Sentiments, July 20, 1848

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Address to Judiciary Committee of the New York State Legislature, January 1, 1860

- Adelaide Johnson, The Basics, 1920 [see the gallery below]

- Maya Angelou, To Form A More Perfect Union, 1977 [see the gallery below]

- Senators on Suffrage webpage

Background Knowledge

Students should be familiar with the Declaration of Independence and the high ideals promoted by the American Revolution—liberty, equality, natural and civil rights and responsible citizenship.

Sequence and Procedure

Part One: Women of the Revolution

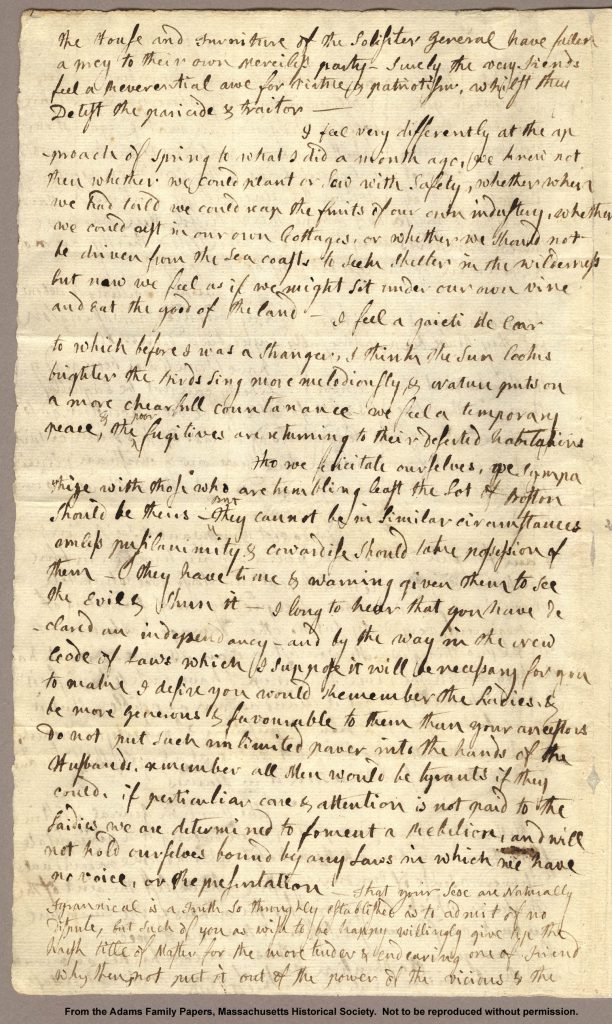

On March 31, 1776, Abigail Adams wrote a letter to her husband John who was serving in the Continental Congress during their debate over American independence. Share the following excerpt of her letter with students assembled in small groups or pairs and ask them to find the main idea.

I long to hear that you have declared an independency—and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.

Have students share their responses with the class. Inform students about the contemporaries of Abigail Adams in Massachusetts who also served as advocates for the education and increasing role of women in eighteenth-century society like Mercy Otis Warren and Phillis Wheatley. If time and resources permit, students could investigate Warren and Wheatley’s contributions.

Share the following observation with students from Elizabeth F. Ellet’s 1848 book The Women of the American Revolution:

Except for the Letters of Mrs. Adams, no fair exponent of the feelings and trials of the women of the Revolution had been given to the public . . . We have no means of showing the important part she bore in laying the foundations on which so mighty and majestic structure has arisen . . . individual instances of magnanimity, fortitude, self-sacrifice and, and heroism . . . to which . . . we are not less indebted for national freedom, than to the swords of our patriots who poured out their blood.

Ask students to summarize Ellet’s opinion—what does she claim?

In small groups, have students research one of the following revolutionary characters—Deborah Sampson, Margaret Corbin, Molly Pitcher or Nancy Hart—who were moved to take part in America’s struggle on the field of battle. Student research groups should record five facts about each woman to share with the class.

After completing their research, ask the groups to share their information with the class.

Next ask students—in their small groups or pairs as before—to examine the following excerpt of the New Jersey Constitution adopted on July 2, 1776, and to summarize the main idea.

4. That all Inhabitants of this Colony of full Age, who are worth Fifty Pounds proclamation Money clear Estate in the same, & have resided within the County in which they claim a Vote for twelve Months immediately preceding the Election, shall be entitled to vote for Representatives in Council & Assembly; and also for all other publick Officers that shall be elected by the People of the County at Large.

Have the groups share their ideas as a class. Explain that New Jersey was the fourth state to adopt a constitution (two days before the release of America’s Declaration of Independence) and that—as evidenced by the reading excerpt—it was the first state to enfranchise women and people of color (“all Inhabitants”) to vote. This right existed until 1807 when a law was passed explicitly limiting voting to white men.

Part Two: Revolutionary Ideals in the Struggle for Women’s Rights

Have students read the following passage by Anne Hollingsworth Wharton introducing a republished edition of The Women of the American Revolution from 1900:

a prophecy of the future as well as a summary of past events . . . if as Mr. Froude says,‘ history is a voice forever sounding across the centuries the laws of right and wrong,’ the reader of to-day may draw from the record of the lives of these women of yesterday, lessons in courage, endurance, fidelity to principle and unselfish devotion to their country, that may well prove an inspiration to higher ideals of citizenship and broader patriotism in the future.

Ask students to find the main idea of Wharton’s introduction and to share it with the class.

Introduce students to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an abolitionist activated as a women’s rights leader when she and other female delegates were denied seats at the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840. Stanton, convinced women should hold a convention demanding their own rights, helped organize the first conference to address women’s issues in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. The Declaration of Sentiments of the Seneca Falls Convention, signed by sixty-eight women and thirty-two men, demanded the rights of women as right-bearing individuals be acknowledged.

Ask students to compare the following passage from the Declaration of Independence—

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights…that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men . . . That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new Government…Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government.

—and this excerpt from the Declaration of Sentiments:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men and women are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights…that to secure these rights, governments are instituted . . . Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government . . . Such has been the patient sufferance of the women under this government, and such is now the necessity which constrains them to demand the equal station to which they are entitled.

As a class, discuss observations about what is similar and what is different—ask students what the essential similarities and differences are, and discuss the semantics of each document. Ask the class why the authors of the Declaration of Sentiments chose to imitate the Declaration of Independence.

In small groups, have students compare the excerpted passage of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s January 1, 1860, Address to the Judiciary Committee of the New York State Legislature to the Declaration of Independence. Ask them to record at least three occasions when Stanton uses language that refers to the Revolutionary generation.

‘If the citizens of the United States should not be free and happy, the fault,’ says Washington, ‘will be entirely their own.’ Yes, gentlemen, the basis of our government is broad enough and strong enough to securely hold the rights of all its citizens, and should we pile up rights ever so high, and crown the pinnacle with those of the weakest woman, there is no danger that it will totter to the ground. Yes, it is woman’s own fault that she is where she is. Why has she not claimed all those rights, long ago guaranteed by our own declaration to all the citizens of this Republic? . . . It is declared that every citizen has a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness . . . Can woman be said to have a right to life, if all means of self-protection are denied her—if, in case of life and death, she is not only denied the right of trial by a jury of her own peers, but has no voice in the choice of judge or juror, her consent has never been given to the criminal code by which she is judged? Can she be said to have a right to liberty, when another citizen may have the legal custody of her person; the right to shut her up and administer moderate chastisement; to decide when and how she shall live, and what are the necessary means for her support? Can any citizen be said to have a right to the pursuit of happiness, whose inalienable rights are denied; who is disfranchised from all the privileges of citizenship; whose person is subject to the control and absolute will of another? . . . ‘Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.’ ‘Taxation and representation are inseparable.’ These glorious truths were uttered for some higher purpose than to decorate holiday flags, or furnish texts for Fourth of July orations . . .

Have the groups share their observations with the class.

On September 16, 1918, suffragists staged a protest at the statue of the marquis de Lafayette in Washington’s Lafayette Square. They chose the statue to dramatize the connection between their cause and the ideals of the American Revolution (Library of Congress).

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

To commemorate the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, the National Woman’s Party commissioned sculptor Adelaide Johnson to create a statue based on her busts of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott. Ms. Johnson wanted to leave the work incomplete to reflect the idea that the work of women’s equality was unfinished. After brief display in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in 1921, the sculpture was moved out of sight into the Capitol’s crypt, where it remained until 1997 when it was returned to the rotunda.

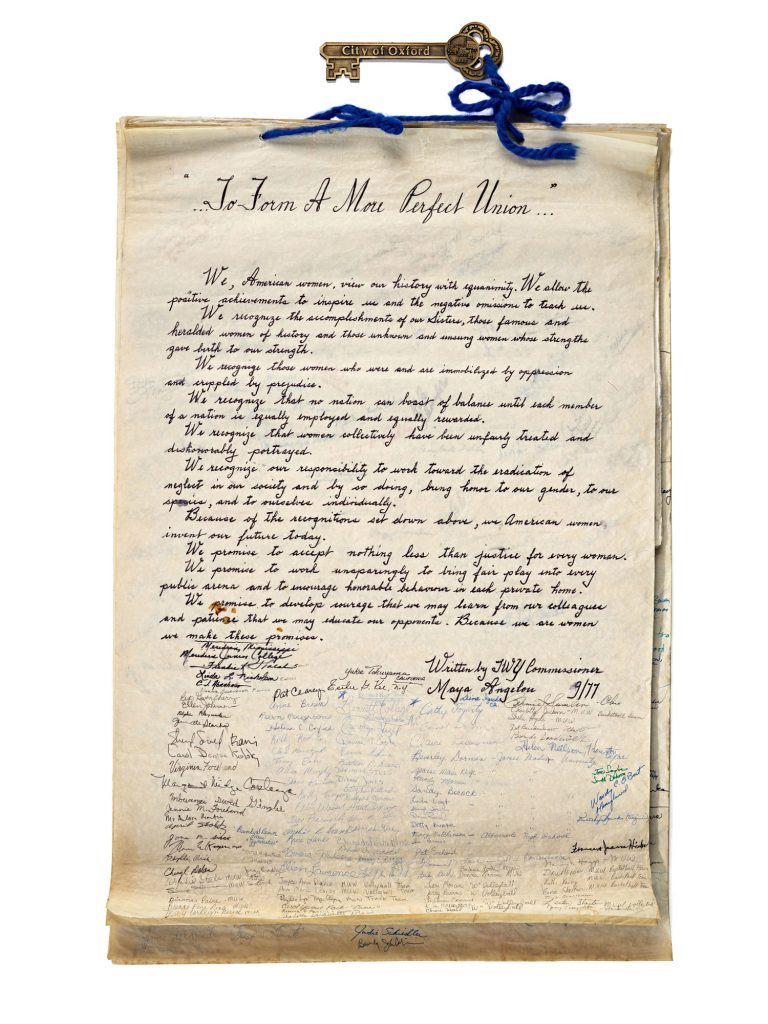

In November 1977, fifty-seven years after winning the vote, over two thousand delegates gathered in Houston, Texas, to attend the National Women’s Conference. The federally funded conference was the most purposely diverse and demographically representative group ever assembled in the United States. Each state sent delegates to debate proposals promoting equal rights and ending discrimination toward women to send to the president and Congress for action.

At the conference’s opening ceremony, poet Maya Angelou read a poem she had composed that linked past and present women’s rights activism titled “To Form a More Perfect Union.” It acknowledged history’s “positive achievement to inspire us and the negative omissions to teach us.” It also recognized “the accomplishments of our Sisters, those famous and heralded women of history and those unknown and unsung women whose strengths gave birth to our strength.” Approximately two thousand runners relayed Angelou’s poem and a lighted torch 2,610 miles from the site of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York to the conference’s Texas location—symbolically passing the flame from the suffragists to a new generation of women’s rights activists.

Ask students to propose possible additions to either Angelou’s poem or Johnson’s sculpture, explicitly referring to a woman or women from the eighteenth century. Students should support their work with evidence from primary sources and be prepared to share their work with the class.

Extension

Direct students to explore the Senators on Suffrage webpage maintained by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and investigate the evolution of the women’s movement in the twenty-first century, citing modern challenges and the individuals who embody the spirit of the eighteenth-century women who fought to secure our highest ideals.

Revolutionary Achievements Category

Highest Ideals

Exploring the Revolution Category

The Legacy of the Revolution

Abigail Adams to John Adams

March 31, 1776Massachusetts Historical Society

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency — and by the way in the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

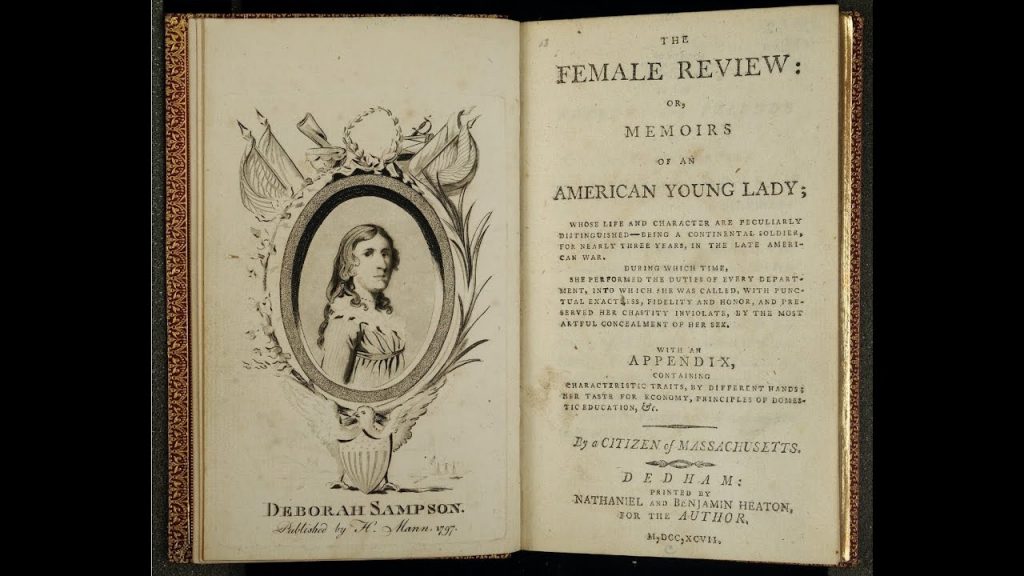

Deborah Sampson at War

Rachel Nellis

May 15, 2020The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Librarian Rachel Nellis discusses Herman Mann’s The Female Review: or, Memoirs of an American Young Lady, a 1797 biography of Deborah Sampson, a soldier in the Massachusetts Line and one of the first female pensioners of the American Revolution. Mixing fact with romantic inventions, the book was published to support Deborah’s application for a pension, which she was granted in 1805. Sampson’s life and the creation of this book are a starting point for discussion of the treatment of enlisted men and woman combatants after the war.

Women Who Followed the Continental Army, Part 3 of 5: Molly Pitcher: Women as Combatants

Carol Berkin

April 10, 2014The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

In the popular imagination, men conducted the Revolutionary War and the Continental Army and its encampments were an all-male environment. Professor Berkin reveals that, in reality, women and children accompanied the army and provided important services to sustain it, including cooking and laundering. The presence of these women decreased desertion and supplied necessary labor, although, as a logistical headache and a potential distraction, it at times frustrated George Washington.

Moll Pitcher at the Battle of Monmouth

D. M. Carter, artist and John Roger, engraver

New York, 1856The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Battle scene with Molly Pitcher in the center assisting two solders fire a cannon next to an officer who lies mortally wounded. In the background to the right are a group of officers on horseback, the first of which appears to be George Washington.

Nancy Hart (Georgia)

Felix Darley, artist and Charles Regnier, engraver

New York: Groupil & Co., 1853The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Scene of Nancy Hart, holding a rifle as her daughter crouches behind her after being discovered passing the rifles of the five British Loyalist's to her father while the enemy were eating the meal they had required Nancy Hart to prepare for them. Confronted by the soldiers, Nancy Hart used one of their rifles to kill one man and injure a second after which the enemy surrendered.

The Basics

Adelaide Johnson

1920United States Capitol

This sculpture was presented to the U.S. Capitol as a gift from the women of the United States by the National Woman's Party and was accepted on behalf of Congress by the Joint Committee on the Library on February 10, 1921. The unveiling ceremony was held in the Capitol Rotunda on February 15, 1921, the 101st anniversary of the birth of Susan B. Anthony, and was attended by representatives of over seventy women's organizations. The Committee authorized the installation of the monument in the Crypt, where it remained on continuous display. In accordance with House Concurrent Resolution 216, which was passed by the Congress in September 1996, the sculpture was relocated to the Rotunda in May 1997. From left to right the figures represent: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott.

To Form A More Perfect Union

Maya Angelou

1977National Museum of American History

African American poet Maya Angelou linked women’s rights activism past and present with her poem “To Form A More Perfect Union.” It acknowledged history’s “positive achievement to inspire us and the negative omissions to teach us.” The poem committed participants to honor the famous and unsung, recognize the challenges that others face, and seek justice for all women.