Evaluating Historical Interpretations

The aim of The Revolutionary Conversation is to introduce students to the art of historical interpretation through the use of short, carefully chosen selections by some of the finest historians of the American Revolution. As teachers we want our students to think critically about the past, and there is no better way to do that than to share examples of the finest thinkers on the American Revolution marshaling evidence to frame interpretations of the past.

Garry Wills, Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence

What did the Declaration of Independence mean? Where did Jefferson get his ideas? Late in life, Jefferson wrote that the Declaration simply reflected widely held views and mentioned the influence of Aristotle and Cicero as well as seventeenth century Englishmen Algernon Sidney and John Locke. Most historians have traced Jefferson’s major ideas to Locke, the philosophical founder of liberal individualism. Garry Wills takes a different approach, tracing the ideas in the Declaration of Independence to the Scottish moral philosophy of Francis Hutcheson, who argued that societies were formed not be individuals seeking their private interests, but by individuals seeking the happiness of the whole. This argument has been widely praised and also widely criticized.

Inventing America

David McCullough, John Adams

In 1779 John Adams returned from his first diplomatic mission to Europe and was promptly chosen to represent the town of Braintree in the conventional called to prepare a constitution for Massachusetts. The convention appointed Adams to a committee to write the constitution, which appointed Adams and two others as a subcommittee to draft the document. The other two asked Adams to do the work. The resulting constitution was entirely Adams’ work. In this lesson, students read and analyze David McCullough’s narrative account of this critical moment of the Revolution and in the life of one of its most important leaders.

John Adams

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution

The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution was recognized soon after it appeared in 1969 as one of the most important interpretations of the shaping of the Revolution ever published. A great deal had been written about the philosophical origins of the American Revolution in the middle decades of the twentieth century, but none of that work made sense of the extraordinary amount of anxiety American colonists expressed about British government “conspiracies” to deprive them of their liberties. Bailyn argues that those ideas were shaped by their reading of informal English political writings, most of it decades old, that warned about government officials and their supporters subverting traditional English liberties. Bailyn contends that these “ideological” origins of the Revolution were as important as the philosophical ones, and made sense of the anxious tone of Revolutionary politics.

Ideological Origins

David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride

The course of complex events like the American Revolution, David Hackett Fischer writes, depends on the choices and actions of individuals. History is thus “contingent” on those choices and actions. It is not determined exclusively by impersonal forces like class conflict, demographic change, or large-scale economic shifts. Fischer uses the Revolutionary career of Boston silversmith Paul Revere to make this case, building a narrative account of the shaping of the Revolution in New England around Revere and the people with whom he interacted to demonstrate that the British actions and American reactions were shaped by the choices historical actors made.

Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution

The aim of The Revolutionary Conversation is to introduce students to the art of historical interpretation through the use of short, carefully chosen selections by some of the finest historians of the American Revolution. As teachers we want our students to think critically about the past, and there is no better way to do that than to share examples of the finest thinkers on the American Revolution marshaling evidence to frame interpretations of the past.

Radicalism of the American Revolution

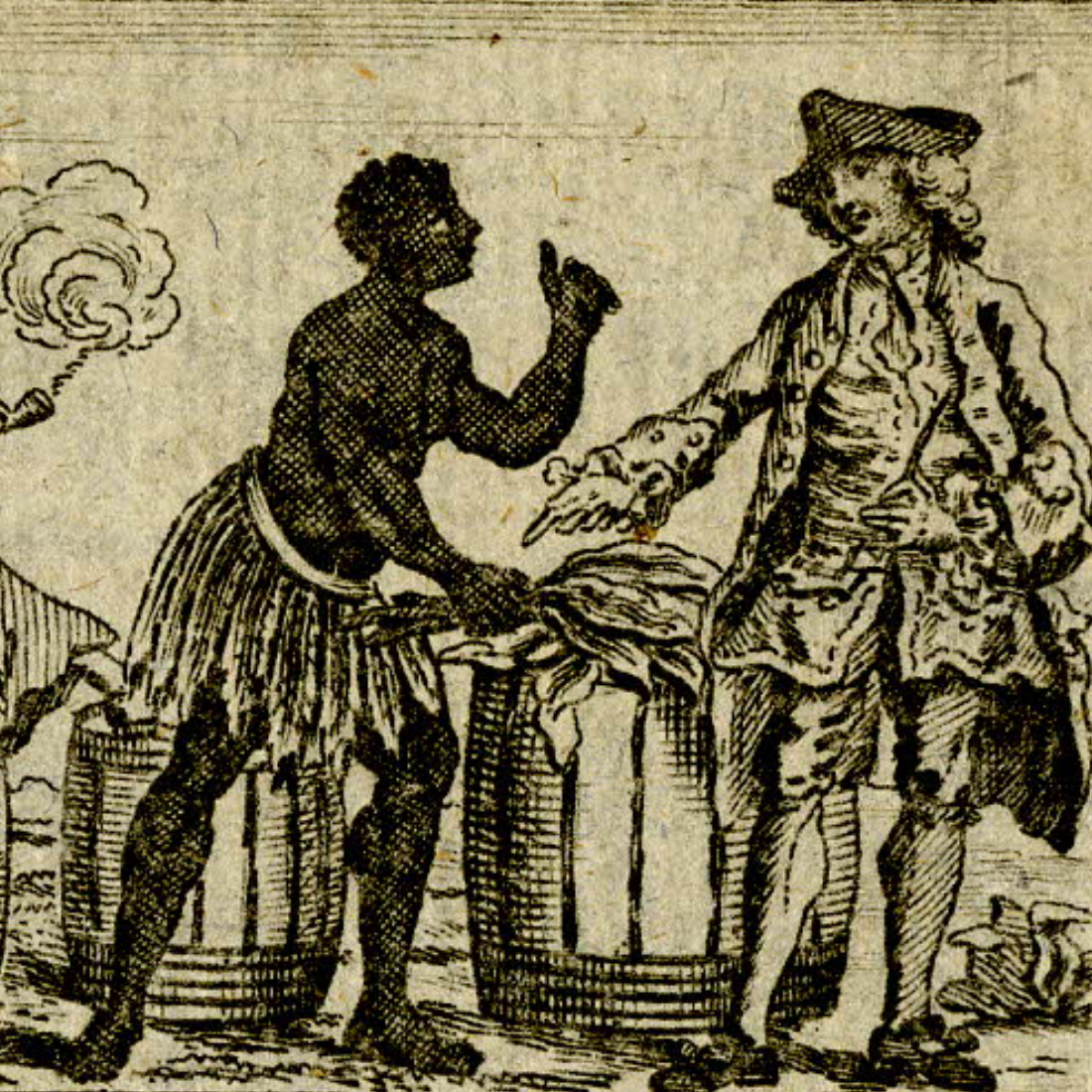

Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom

In Virginia the Revolution in favor of freedom was led by men who owned large plantations and enslaved, in many cases, hundreds of people. Edmund S. Morgan argues that slavery, ironically, made it possible for planters to favor a republic. The eighteenth-century Virginia gentry, like their counterparts in Britain, was opposed to increasing the political influence of the poor. The fact that the overwhelming proportion of Virginia’s laboring people were enslaved and therefore denied the privileges of citizenship assured that independent property owners would control public life in republican Virginia. Slavery thus made it possible for gentleman planters to advocate for liberty, which would be enjoyed by whites only.

American Slavery, American Freedom

Winthrop Jordan, White Over Black

To a fundamental question—did racism lead to slavery or was it a consequence of it? Winthrop Jordan argues that sixteenth-century Englishmen were predisposed to regard black Africans as inferior. Those prejudices, Jordan finds, were largely irrational—based on cultural ideas about blackness, non-Christians, remote parts of the world, and other factors. Racism developed with slavery, as the debased conditions of enslavement turned unthinking prejudices into self-fulfilling ones. The Revolutionary commitment to universal equality challenged slavery and spurred the movement that brought it to an end, but it did not overcome what Jordan calls “the power of irrationality” that helped slavery endure until the Civil War.

White Over Black