Two of the fifteen presentation swords awarded by the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War are preserved in the Institute’s collections. This example was awarded to Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, the longest-serving aide-de-camp to George Washington.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress awarded fifteen presentation swords to officers who displayed exceptional bravery and commitment to the cause. Not all of these swords are known to survive, but two are preserved in the Institute’s collections—the only institution to own more than one of these treasured artifacts. One of these two swords was awarded to Lt. Col. Samuel Smith of the Maryland Line for his gallant leadership in the defense of Fort Mifflin in November 1777. The second sword was awarded to Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, the longest-serving aide-de-camp to George Washington and the man entrusted with carrying the momentous news of the victory at Yorktown to Congress in October 1781. These elegant, French-made swords of silver and gold document the importance of the officers’ actions and bear rich symbols of American independence and the new American republic.

The tradition of presenting a sword as a mark of general esteem or a reward for a specific heroic act dates back at least several centuries to European and Middle Eastern precedents. The swords awarded by Congress during the Revolutionary War were the first American presentation swords in what would become a long tradition of recognizing military heroism with precious commemorative objects. Congress was the only entity to award swords during the Revolution, but beginning with the War of 1812, states, cities and private organizations commissioned their own swords to bestow on military leaders. American presentation swords were most popular from the War of 1812 to World War I, after which they went out of style.

The seventh sword awarded by Congress during the Revolution honored Lt. Col. Samuel Smith. On November 4, 1777, Congress, having “a high sense of the merit of Lieutenant Colonel Smith, and the officers and men under his command, in their late gallant defence of Fort Mifflin, on the river Delaware,” resolved “that an elegant sword be provided by the Board of War, and presented to Lieutenant Colonel Smith.” The American fort on Mud Island just south of Philadelphia, and several other patriot installations, had prevented British supply ships from reaching the city since early October, while also allowing General Washington time to move his troops into winter quarters at Valley Forge. An American force under the command of Samuel Smith still held Fort Mifflin when Congress passed its resolution on November 4, but Smith’s defense of the fort was not yet over.

Washington ordered Smith to form a garrison at Fort Mifflin on September 23, writing, “the keeping of the fort is of very great importance, and I rely strongly on your prudence, spirit and bravery for a vigorous & persevering defense.” Half of the four hundred men in the garrison were from Smith’s Fourth Maryland Regiment. Officially, Washington had named a Prussian volunteer, Col. Henry Leonard Philip, baron d’Arendt, as the commanding officer at Fort Mifflin, but Colonel Arendt was chronically ill during the siege, leaving command of the fort to Lieutenant Colonel Smith. British cannons on the mainland began bombarding Fort Mifflin in early October. Smith’s men unsuccessfully attempted to capture the enemy’s artillery and did not have the fire power from the fort’s batteries to halt their bombardment. By early November the British had added floating batteries and unleashed a ferocious, constant barrage of shells on the partially earthen fort. On November 11—a week after Congress’ award—Smith reported that “by tomorrow night everything will be levelled” and if the British should “storm us I think we must fall—however even as it is your opinion I will keep the garrison tho’ I lose mine and my soldiers lives.” Smith did indeed almost lose his life. The same day, a cannon strike hit his barracks, knocking him unconscious and injuring his hip and left arm. Smith was evacuated to nearby Fort Mercer, where he remained when his garrison abandoned Fort Mifflin four days later. The Americans’ perseverance inspired respect even from the enemy. A British officer remarked: “the behavior of the enemy … did them honor, nor did they quit the place ‘till their defenses were ruined, and the works rendered to rubbish, setting the works in a blaze when they could defend it no longer.”

Samuel Smith (1752-1839) had begun his Revolutionary War service in January 1776 as a captain in William Smallwood’s Battalion, with which he fought at the Battle of Brooklyn. By the end of the year he had become major of the Fourth Maryland Regiment, and he was promoted to lieutenant colonel in February 1777. He helped lead the regiment in the Battle of Brandywine, through the siege of Fort Mifflin, during the winter at Valley Forge, and in the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse. Smith resigned from the Continental Army in May 1779 and returned to his family’s shipping business in Baltimore. After the war he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, oversaw the defense of Baltimore during the War of 1812 and later served as mayor of the city. He was an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland and served as its president from 1828 until his death.

Smith’s fellow Marylander, Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman, was the recipient of the eleventh sword awarded by Congress during the Revolution. On October 29, 1781, Congress resolved to present to Tilghman “a horse properly caparisoned, and an elegant sword, in testimony of their high opinion of his merit and ability.” Rather than honoring battlefield valor, this award recognized Tilghman’s indispensable service to George Washington as the commander-in-chief’s longest-serving aide-de-camp—a relationship that inspired the general to bestow on Tilghman the honor of delivering to Congress the Articles of Capitulation signed by British general Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown. Tilghman had been with Washington through the siege, the final assaults on the British redoubts, Cornwallis’ surrender and the capitulation ceremony. The day after the British capitulation, Tilghman left for Philadelphia, arriving in the early morning hours of October 24 to proclaim the news to President Thomas McKean. Along with the Articles of Capitulation, Tilghman transmitted to McKean a letter from Washington, in which the general praised his aide: “His Merits, which are too well known to need any observations at this Time, have gained my particular Attention—& I could wish that they may be honored by the Notice of your Excellency & Congress.” Five days later Congress voted to award Tilghman with a presentation sword.

Tench Tilghman (1744-1786) joined the patriot cause in late summer 1775, when Congress appointed him secretary to a commission that traveled to New York to persuade the Iroquois Confederacy to remain neutral in the Revolutionary War. When he returned he joined a Philadelphia militia company and, in the summer of 1776, was promoted to captain in the Pennsylvania battalion of the Flying Camp attached to the Continental Army. Tilghman first met George Washington in August 1776 and volunteered to serve with the commander-in-chief’s staff. For the next seven years, Tilghman excelled drafting the general’s correspondence, distributing his orders, reporting news from the battlefield and contributing to Washington’s headquarters in any other way he could. He was at Washington’s side from the surprise attack on Trenton to the turmoil at Monmouth and triumph at Yorktown. Washington formally appointed Tilghman an aide-de-camp in his General Orders of June 21, 1780, but Tilghman would not receive a military rank or salary for another year. In supporting Tilghman’s commission from Congress, Washington wrote that his aide “has been a zealous servant & slave to the public, & a faithful assistant to me for near five years, great part of which time he refused to receive pay.” Congress appointed Tilghman a lieutenant colonel on May 30, 1781. As the war wound down after Yorktown, Tilghman received an extended leave of absence from the army to recuperate his health and to court his future wife, Anna Maria Tilghman. Lieutenant Colonel Tilghman resigned his commission on December 23, 1783—the same day Washington famously resigned his commission in front of Congress in Annapolis. Tilghman settled in Baltimore after the war and resumed his mercantile business. He became an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, but he died just three years later at the age of forty-one.

These presentation swords were intended as purely ceremonial and commemorative objects. Their basic design followed the pattern of the typical French small sword, which was fashionable on both sides of the Atlantic. The slight, elegant hilt compliments the small, straight, tapered blade that is triangular in cross section. The silver hilt is embellished in yellow and rose gold with symbols of the new American republic, including laurel wreaths, liberty caps and military trophies. The grip bears the arms of the United States on one side and an inscription on the other noting the recipient of the sword and the date of the Congressional resolution. The entire length of the blade is blued, with gilt etched designs of floral sprays and military trophies. The brilliant, iridescent surface—sometimes called peacock blue—was produced by the niter bluing process, in which the finished, highly polished steel blade was dipped in a molten salt bath of potassium and sodium nitrate for a period of time to produce the decorative finish. On the back side of the blade beginning at the ricasso is a gilt panel bearing the inscription of the maker, the Liger workshop in Paris. The presentation swords were originally accompanied by a scabbard of shagreen—an untanned leather made of fish skin—with silver mounts decorated similarly to the hilt. The scabbard for the Samuel Smith sword retains its original shagreen exterior, while the scabbard for the Tench Tilghman sword has a black leather exterior, probably added later as a replacement for the original shagreen.

That these presentation swords were made at all was due largely to the efforts of David Humphreys, a Revolutionary War officer from Connecticut. First serving as a captain in the Sixth Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Army, Humphreys became an aide-de-camp to George Washington in June 1780—alongside fellow aide Tench Tilghman. Like Tilghman and Samuel Smith, Humphreys was awarded a sword by Congress, in appreciation of his delivery of the British standards surrendered at Yorktown to Congress in Philadelphia in early November 1781. After the war, Congress appointed Humphreys secretary to the American commissioners in Paris—Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams—charged with negotiating commerce treaties with European and North African nations. Beyond his formal duties, Humphreys saw an opportunity to nudge Congress’ presentation swords towards completion.

Because of difficulties in allocating resources to the project during the war, only one of the fifteen swords had been made by 1784. The sword awarded to the marquis de Lafayette in 1778 was completed in Paris the following year—largely due to the efforts of Benjamin Franklin, the United States minister to France. In January 1781 the Board of War reported to Congress that “it is impossible to gratify the wishes of the gentlemen entitled to swords by Resolutions of Congress under our present embarrassments even if they could be manufactured here with sufficient neatness.” (Several years earlier, Col. Benjamin Flower, commander of the army’s Artillery Artificer Regiment, had a few swords made as models for the Congressional presentation swords, but the Board of War considered them “too badly executed to be presented as a token of National approbation.”) Congress directed that eight “plain, but elegant silver mounted small swords” be added to the list of supplies to be imported from Europe, but they were apparently omitted from the final shipment.

Before leaving for France, Humphreys asked Robert Morris, superintendent of finance, when he would receive his presentation sword. Morris—perhaps sensing an opportunity of his own—responded in June 1784 directing Humphreys to oversee the production of ten swords that remained to be procured. Morris conceded that the “Swords can best be executed in Europe” and instructed Humphreys that “the Articles when purchased you will be pleased to have shipped by some safe Conveyance directed for the Secretary at War … Be pleased also to have all these articles executed agreeably to the Resolutions of Congress respecting them”—although the extent of the description Congress provided in the resolutions was simply “an elegant sword.”

In July 1784 Humphreys sailed for France and, within several months, began making arrangements for the swords. He chose the Liger family workshop in Paris—led by master sword maker Claude-Raymond Liger (1720-1802) and his son Pierre-Ambroise Liger—for the commission. Liger had made Lafayette’s Congressional presentation sword five years earlier, which no doubt influenced Humphreys’ selection. In mid-March 1785 Humphreys proposed to Congress that the swords be “constructed in precisely the same fashion, to wit, the hilt to be of silver, round which a foliage of laurel to be enameled in gold in such a manner as to leave a medallion on the center sufficient to receive the arms of the United States on one side, and on the reverse an inscription in English, ‘The United States to Colonel Meigs July 25, 1777.’ And the same for the others.” Congress approved the design, and Humphreys arranged to pay Liger 6,500 livres to secure the contract for the ten swords.

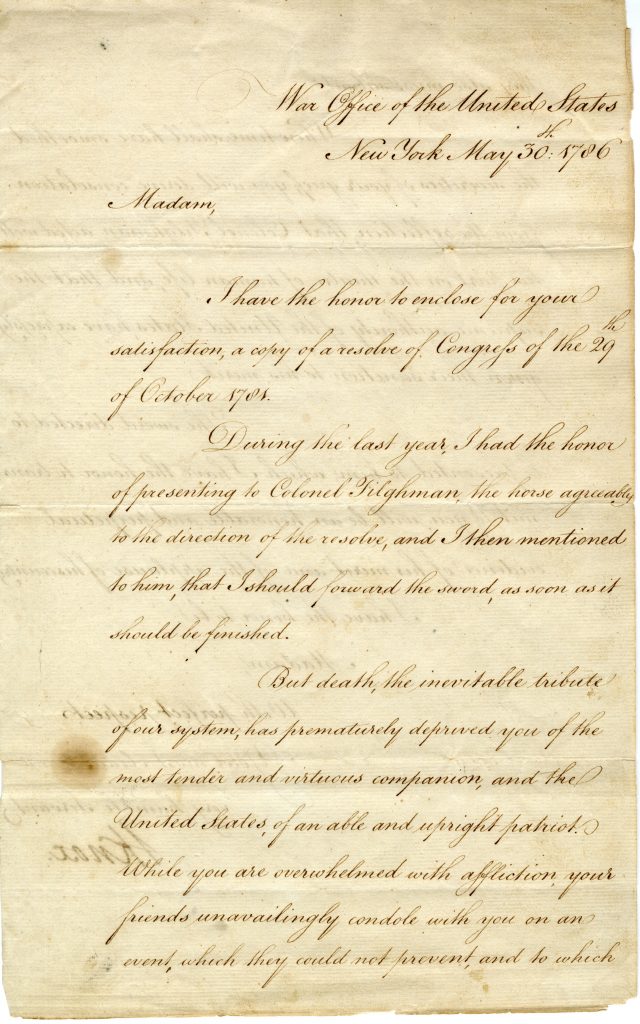

The presentation swords were finished by early 1786, and Humphreys returned to the United States with them in late April 1786. He quickly delivered them to Secretary of War Henry Knox in New York for distribution. Knox transmitted each sword to the honoree with a letter and a copy of the Congressional resolution. In the case of Tench Tilghman’s sword, Knox addressed his letter to Tilghman’s widow, Anna Maria, as her husband had died a month earlier. Writing on May 30, 1786, Knox offered the following tribute: “death, the inevitable tribute of our system, has prematurely deprived you of the most tender and virtuous companion, and the United States, of an able and upright patriot. … Colonel Tilghman acted well his part on the theatre of human life.” Knox concluded that the sword awarded to Lieutenant Colonel Tilghman “will be an honorable and perpetual evidence of his merit and of the applause of his country.”

Mrs. Tilghman treasured her husband’s sword until her death in 1843. It descended in the family to their great grandson, Oswald Tilghman, who brought the sword to the centennial celebration at Yorktown in 1881. His son, Harrison Tilghman, inherited the sword and bequeathed it to the Society of the Cincinnati, which was finalized in 1965. Samuel Smith’s sword also remained in the family for generations. He was so proud of the award that he wore the sword when sitting for a portrait painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1817 (collection of the Maryland Historical Society). Seven years later, he allowed it to be displayed at a dinner in Baltimore hosted by the Maryland branch of the Society of the Cincinnati in honor of the marquis de Lafayette during the Frenchman’s tour of the United States. Samuel Smith bequeathed it to his son, John Spear Smith. The sword descended to Samuel Smith’s great-great-great grandson Burr Noland Carter II, who donated it to the Society of the Cincinnati in 1999.

View More Armaments

Presentation sword and scabbard awarded by the Continental Congress to Samuel Smith

Claude-Raymond Liger (1720-1802), Paris

1785Gift of Burr Noland Carter II, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1999

The presentation sword awarded by Congress to Lt. Col. Samuel Smith in 1777 survives with its original shagreen scabbard.

Presentation sword and scabbard awarded by the Continental Congress to Tench Tilghman

Claude-Raymond Liger (1720-1802), Paris

1785Bequest of Harrison Tilghman, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1965

The presentation sword awarded by Congress to Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman in 1781 survives with its original scabbard covered in black leather.

Maker’s mark on the Tilghman sword

The three-inch-long gilded panel on the back side of the blade on the Tilghman sword bears the maker’s mark, identifying Liger as a fourbissier, or swordsmith, with the duc de Chartres and comte de Clermont as patrons and a workshop located on Rue Coquillière in Paris.

Henry Knox to Mrs. Tench Tilghman

May 30, 1786Bequest of Harrison Tilghman, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1965

One month after Tench Tilghman died, Secretary of War Henry Knox transmitted his sword to his widow, writing that the sword “will be an honorable and perpetual evidence of his merit and of the applause of his country.”