Pieces from George Washington’s Society of the Cincinnati porcelain service have the hallmark blue Fitzhugh border around the rim.

The Society of the Cincinnati porcelain—decorated with the organization’s Eagle insignia held by the allegorical figure Fame—reflects the Society’s purpose to celebrate and preserve the memory of the achievement of American independence. Made in the late eighteenth century, this Chinese export porcelain was used on the tables of original Society members from New England to Virginia and further south, including George Washington and Henry Knox. The Institute’s museum collections contain nine pieces of this important porcelain.

The central character in the story of the Society porcelain is Samuel Shaw (1754-1794), a Revolutionary War veteran, original member of the Society and prominent figure in the United States’ early trade with China. A native of Boston, Shaw rose to the rank of captain in the Continental Artillery during the Revolutionary War. He served as an aide-de-camp to Maj. Gen. Henry Knox from June 1782 to November 1783. During the same time, he also helped Knox organize the Society of the Cincinnati in the army’s camps along the Hudson River. Shaw acted as the secretary of the group and penned the minutes of its formative meetings during the summer of 1783.

At a meeting on June 10, 1783, early Society leaders approved Pierre L’Enfant’s design for the organization’s insignia, a double-sided badge in the shape of a bald eagle bearing scenes of the Society’s namesake, the ancient Roman hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. This design was intended as a model for the gold and enamel badges, known as the Eagle, that L’Enfant oversaw the manufacture of in Paris in 1784. It also became the basis for the decoration on the Society porcelain that Shaw commissioned in China the same year.

On February 22, 1784, the Empress of China, the first American ship to conduct trade directly with China, embarked on the long voyage from New York to Canton (Guangzhou), where it arrived six months later. Shaw was aboard as the ship’s agent, or supercargo, and was charged to act on behalf of American entrepreneurs Robert Morris and Daniel Parker. These men were eager to join their European counterparts in the lucrative trade with China. Among the commodities Shaw planned to acquire in Canton—including tea, silk, lacquer ware and ivory—was a significant cargo of porcelain, and in particular, “something emblematic of the institution of the order of the Cincinnati executed upon a set of porcelain.”

Shaw carried with him on the voyage one of L’Enfant’s watercolor drawings of the Society insignia and several other graphics to inspire the design for the Society porcelain. Without any formal direction or commissions from the Society’s leaders, Shaw conceived of an elaborate grouping of figures to celebrate the organization’s founding and ideals: “My idea was to have the American Cincinnatus, under the conduct of Minerva, regarding Fame, who, having received from them the emblems of the order, was proclaiming it to the world. For this purpose I procured two separate engravings of the goddesses, an elegant figure of a military man, and furnished the painter with a copy of the emblems, which I had in my possession.” But the design had to be simplified, as Shaw found that the Chinese enameller “was unable to combine the figures with the least propriety … I could therefore have my wishes gratified only in part.” The Society porcelain would ultimately bear only the winged figure of Fame and the Eagle insignia suspended from a blue-and-white ribbon held in her left arm.

There is only one service of Society porcelain known to have been made in this famous pattern, a 302-piece dinner and tea service that was owned by George Washington. The Institute’s museum collections include three dinner plates and one platter from this service. It was executed in late 1784 or early 1785 on the fashionable and ubiquitous blue-and-white Fitzhugh border pattern of whimsical flowers, butterflies and other Chinese motifs. The border’s namesake, Thomas Fitzhugh, director of the Honourable East India Company, ordered a porcelain service with a similar border design in 1780, and, over time, the style’s name became synonymous with his. Porcelain services with this border design were so popular that Chinese artists in Canton probably had a plentiful supply already in stock, ready to be embellished with armorial or other designs prescribed by their clients.

Most of the porcelain available in Canton was produced in Jingdezhen, some four hundred miles to the northwest of the port city and believed to be the largest industrial complex in the world in the late eighteenth century. The fine, hard paste porcelain made there used kaolin, a type of pure white clay and crushed quartz that made the china very smooth and translucent white. The over-glaze decoration of the Society insignia was added after the porcelain had been glazed and fired.

The first set of Society porcelain arrived in Baltimore on August 9, 1785, aboard the Pallas, the second American ship to conduct trade with China. An advertisement for the Society service in the Maryland Gazette & Baltimore Advertiser caught the attention of George Washington. Just five days after the announcement appeared, Washington wrote to Tench Tilghman, the general’s former aide-de-camp and fellow Society member living in Baltimore, in the hopes of acquiring a set of the porcelain if it could be obtained at a price “cheaper than common.” But the prices in Baltimore were high enough to discourage any buyers, and the entire lot of Society porcelain was moved to New York and offered for sale the following year. Washington ultimately purchased the service for $150 from the New York firm Constable, Rucker, & Co. in July 1786, with the help of Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, a fellow Society member then serving as a delegate to Congress in New York.

Shaw proved to be a successful merchant and made three more trips to China before his death in 1794. He first returned to Canton in 1786, the same year he was appointed the United States’ first consul to China. By this time, he had purchased a gold Eagle insignia, which he took to China to have additional sets of Society porcelain produced with more precise depictions of the badge. During this voyage or his next in 1790, Shaw commissioned Society tea services for himself and fewer than ten fellow members of the Massachusetts branch of the Society. Preserved in the Institute’s museum collections are five pieces from these services—a sugar bowl and creamer from Shaw’s own service and two saucers and a teacup from Benjamin Lincoln’s.

These tea services, usually consisting of forty-five pieces, feature both sides of the Eagle insignia painted in enamel with gilt highlights. There is no blue-and-white Fitzhugh border, but instead a thin undulating gold-and-black enamel border. Unlike the Washington service, the Eagle appears without the figure of Fame and with a laurel wreath around the Eagle’s head. Each set is personalized with the owner’s initials, or cipher, in gold script. Not all of the recipients have been identified, but they include Henry Jackson, William Eustis, Benjamin Lincoln, Constant Freeman, David Townsend and Henry Knox.

Shaw traveled to China for the fourth and final time in February 1793. He arrived in Canton in November but was soon afflicted by a “disease of the liver incident to the climate.” Shaw departed Canton in March 1794, months before he had planned, and died at sea aboard the Washington off the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, in May 1794. The Society porcelain has become his legacy and without his energies would probably not exist.

Learn More About the Society of the Cincinnati

Design of the Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825)

1783The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

Pierre L’Enfant created multiple copies of his cutout watercolor-on-paper design of the Society’s Eagle, to promote sales of the gold badges among members and to aid the French craftsmen who made the insignia. Samuel Shaw also took one of L’Enfant’s watercolor drawings of the Eagle to China, and it appears on George Washington’s service of Society porcelain.

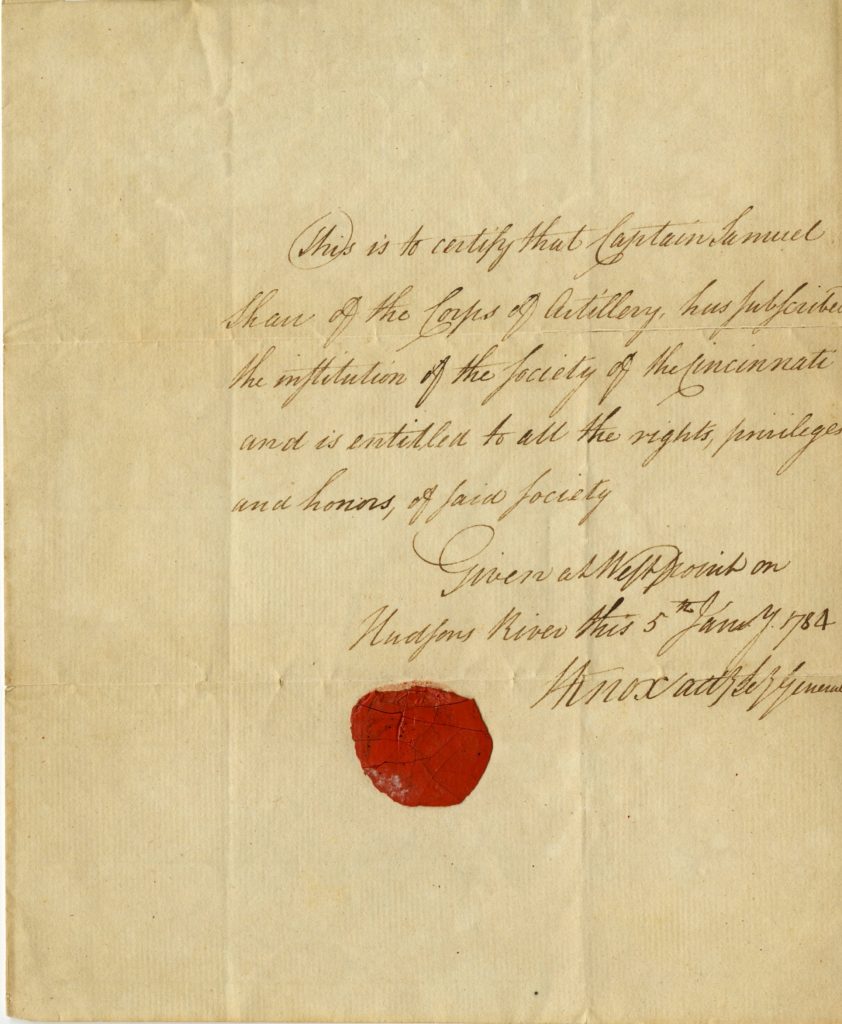

Samuel Shaw’s Society of the Cincinnati membership certificate

January 5, 1784Gift of George Francis Shaw, Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, 1980

Six weeks before leaving on his first voyage to China, Samuel Shaw obtained this handwritten membership certificate identifying him as a member of the Society of the Cincinnati. It was signed by Henry Knox as acting secretary general of the Society.

Creamer and sugar bowl

Jingdezhen, China

ca. 1790Museum Acquisitions Fund purchases, 2008 and 2010

Samuel Shaw’s own Society tea service—which was larger than the others he ordered for his fellow members—included these two pieces. Each of these tea services included the owner's initials, usually below the Eagle.

Society of the Cincinnati Eagle insignia

Nicolas-Jean Francastel and Claude-Jean-Autran Duval, Paris

1784Gift of Harrison Tilghman, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1953

Samuel Shaw probably owned a gold Eagle of this type—made in Paris in the spring of 1784 and sold primarily to American members—although its whereabouts are unknown today. He brought it to China on his later trips so artisans could depict the insignia more accurately on porcelain.

Sugar bowl

Jingdezhen, China

ca. 1790Museum Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2008

Chinese artists used Samuel Shaw’s Society Eagle as a model for the more realistic depiction of the insignia that appears on the tea services Samuel Shaw commissioned. This sugar bowl from Shaw’s service displays each side of the medal on opposite sides of the bowl. The obverse is pictured here.

Teacup and saucer

Jingdezhen, China

ca. 1790Bequest of Margaret Warren in memory of Winslow Warren, 1960

Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln of Massachusetts owned these pieces as part of his Society tea service, which Samuel Shaw brought back from China in 1790. The Institute’s collections also include another saucer from Lincoln’s service.