Slavery, Rights and the Meaning of the American Revolution

By Jack D. Warren, Jr.

June 16, 2020

In the lead essay of the “1619 Project,” Nikole Hannah-Jones claims that the American Revolution was fought to perpetuate slavery and that the nation’s founding ideals were a fraud. She couldn’t be more wrong. The American Revolution secured the independence of the United States from Britain, established a republic, created our national identity and committed the new nation to ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship that have defined our history and will shape our future and that of the world.

Committing the new nation to the principle of natural rights—the idea that people possess certain rights inherent in the human condition—was the achievement on which the others depended. That commitment was the foundation for the long campaign to end slavery and to secure the rights of all Americans. The American Revolution didn’t perpetuate slavery. It set slavery on the path to extinction. The ideals of the American Revolution empower us to hunt down and destroy human trafficking and every other vestige of slavery in the world today. The American Revolution combined hope for a better world with the principles on which a better world will be built.

The injustice of slavery was a rising topic of discussion among some educated people in Britain and France, as well as in Britain’s American colonies, in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. There was, as yet, no abolition movement, nor a clear vision of what a world without slavery would be like. The uneasiness of the first self-conscious critics of slavery was shaped by the sense that enslaved Africans possessed rights that ought to be respected.

This idea—the idea that all people possess what we call natural rights—is so fundamental to us that we find it hard to imagine a time when it was not widely accepted. But in the third quarter of the eighteenth century this idea was just beginning to gain acceptance. The concept of rights, by contrast, was centuries old, and had begun as a way to articulate the limitations on the sovereign power of kings and aristocrats. Rights of that sort were won in struggles between monarchs and their subjects—at first between kings and aristocrats, and later, in England, between the king and his supporters on one side and ambitious, rising gentry and merchants on the other. Titled aristocrats forced King John to sign the Magna Carta, and in the seventeenth century, Parliament and its supporters contended successfully with Stuart monarchs to limit the power of the monarchy and establish the rights of Englishmen, as eighteenth-century British subjects and colonial British Americans used that phrase.

Those rights were regarded in the eighteenth century as the particular heritage of English people, and the English did not regard them as universal. They were the hard-won possession of the English, extended, sometimes grudgingly and with a kind of wary suspicion, to the king’s subjects in Wales, Scotland and his Protestant subjects in Ireland. That those rights extended to the king’s subjects in North America was the subject of disagreement. Reactionary Englishmen in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, like the famous Samuel Johnson, argued that colonists had surrendered the rights of Englishmen when they left England for the American colonies, and could not expect to enjoy the rights that Englishmen at home enjoyed. More generous Englishmen like Edmund Burke rejected Johnson’s argument and sided with the American Revolutionaries in their claim to possess the rights of Englishmen. Nearly all Englishmen agreed that foreigners, including Africans and their descendants, did not enjoy the rights of Englishmen, nor did most Africans enjoy the limited privileges and immunities they afforded to foreign Christians.

The idea that Africans, free or slave, possessed rights depended on a theory of natural rights—of rights inherent in the human condition rather than the possession of a particular people, won through their historical experience. The idea of natural rights had been building since the seventeenth century. It was shaped by a Dutch jurist, Hugo Grotius, and his German follower, Samuel Pufendorf, and given more complete formulation by a Swiss theorist, Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, who synthesized thinking on natural rights in The Principles of Natural Law, published in 1747. It quickly attracted a wide audience and was well known to thoughtful Americans like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The idea that all people possess certain fundamental rights seems obvious to us, because we live in a world in which the idea has wide assent, but it was, as late as 1770, a theoretical construct. No government acknowledged the existence of natural rights. The American Revolutionaries were the first to apply it to the construction of governments.

Principled opposition to slavery, which had previously been expressed by a few, mostly on religious grounds, grew with the development and spread of natural rights theory. Many well-read people in England, and well-read Americans like Benjamin Franklin, were growing uncomfortable with slavery in the last years before the American war. Indeed the controversy between the colonies and Britain that led to the Revolution, which was in some respects a great forensic controversy about rights, stimulated and accelerated thinking on both sides of the Atlantic about natural rights and fed the early development of the antislavery movement on both sides of the ocean.

It is not surprising that the people in England who were most uncomfortable with slavery tended to be vocal defenders of American rights and supporters of the American cause, even during our War for Independence against Britain. They did not see, as Hannah-Jones does, the Revolution as a movement fomented by slaveowners to defend their human property. They saw the Revolution as a principled defense of the rights of Englishmen to which Americans were entitled—this was Edmund Burke’s view—or they saw the Revolution as a truly radical movement based on the natural rights of all mankind. This was the view of the English radical Richard Price, a great friend and admirer of Benjamin Franklin.

Englishmen like Price who believed that governments should be based on natural rights were the exception in the 1770s. They were the avant-garde, not the mainstream. They were the avant-garde in America, too, before the beginning of the war between Britain and the colonies in 1775, but the war forced Americans to reconsider the nature of government authority and to embrace natural rights as the proper basis of government. This was a truly and deeply radical moment in world history. It changed what had been, up to that moment, a regional dispute about legal rights under English law into a revolution in favor of an entirely new theory of rights and consequently a wholly new foundation for government.

Since principled opposition to slavery rested on the idea of natural rights, it is not at all surprising that the first statute abolishing slavery ever written was adopted, not in Britain, but in what might justly be described, at that moment, as the most culturally diverse, philosophically sophisticated and forward-looking place in the western world: Pennsylvania. With a founding creed based on Quaker ideas of moral equality, tolerance, charity and non-violence, eighteenth-century Pennsylvania attracted settlers and religious refugees from several parts of western Europe—people from differing cultural and legal traditions. The idea of natural rights as the basis of government was accepted more readily there than anywhere else, and led logically to the Pennsylvania Statute for the Abolition of Slavery, which was adopted in 1780. Slavery was abolished by law in the states north of Pennsylvania during the Revolutionary generation and as a direct consequence of the Revolutionary appeal to universal natural rights.

Meanwhile thousands of African Americans served in the armed forces that won American independence. As many as nine thousand served in the Continental Army and Navy, in the militia, on privateering vessels and as teamsters or servants to officers. This was about four percent of the men who served in the armed forces, but their terms of service were typically much longer than that of whites. Thus, at any one time, black soldiers, sailors and support personnel probably accounted for between fifteen and twenty percent of the effective strength of the armed forces. They were particularly conspicuous during the latter stages of the war, when white recruitment slowed. Obviously none of these men, properly classed with our nation’s founders, fought to perpetuate slavery.

Hannah-Jones’ claim that “one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery” is not supported by the evidence. Seven months after the Times published this astonishing assertion, the editors changed it to read “some of the colonists decided” as a half-hearted concession to criticism from historians. “In attempting to summarize and streamline,” Hannah-Jones acknowledged, “journalists can sometimes lose important context and nuance. I did that here.” But the difference between “the colonists” and “some of the colonists” is not a matter of nuance or context. It’s a distinction between truth and falsehood.

In fact, both statements are false. No evidence has been advanced to support the claim that anyone supported independence because they feared for the future of their slave property. The editors nonetheless left unchanged Hannah-Jones’ sweeping assertion that “the founding fathers . . . believed that independence was required in order to ensure that slavery would continue.” Having acknowledged, grudgingly, that they went too far, Hannah-Jones and her editors, with the help of the Pulitzer Center, intend to introduce this fabrication into our schools. So much for nuance, context and journalistic integrity.

Hannah-Jones’ contention is based on the false belief that the British Empire—in which slavery was the basis of enormous wealth—was somehow less congenial to slavery than Revolutionary America. Both depended on slave labor, but an American slave owner who looked with concern at the earliest development of antislavery sentiment in England was surely as disturbed by the early development of antislavery sentiment in the revolutionary American states. Whether such anxious slave owners joined the patriot cause or remained loyal to the crown—and consequently to a theory of rights that excluded non-Englishmen, including their slaves—is not clear. It seems logical that any slave owners who were concerned by the earliest anti-slavery thought should have rejected the American Revolution and its basis in natural rights theory. But this is largely conjecture. Little evidence of such anxiety has been found.

In his defense of Hannah-Jones’ claim, her editor Jake Silverstein points to the November 1775 proclamation of Virginia’s last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, offering freedom to slaves who deserted their rebel masters and joined him in suppressing the rebellion. That proclamation, he writes, led fearful slave owners to embrace independence to separate from the British threat to the slave property. This argument will not bear scrutiny. By November 1775 the movement that ended with independence was already far advanced, and no one could have connected Dunmore’s proclamation to British antislavery sentiment. Dunmore owned slaves. His sole aim, as Americans understood perfectly well, was to cripple the productive capacity of the rebels by depriving them of agricultural labor, and to bring the rebellion to its knees by shattering the economy that supported it. That effort failed. It served chiefly to alienate fence-sitting slave owners who hoped to stay out of the war and alienate loyalist slave owners whose slaves fled to the British as readily as the slaves of patriots. That Dunmore and like-minded British leaders were not principled abolitionists is demonstrated by the fact that they sometimes aided loyalist planters in recovering their slaves.

Thousands of slaves fled their masters during the chaos of the war, and some of them ultimately secured their freedom by joining the exodus of loyalist refugees. Former slaves who lived out their lives in Canada found refuge in a corner of the British Empire wholly unsuited to slavery. But the suggestion that Britain or its empire were less complicit in the horrors of slavery than Britain’s former colonies and offered emancipated slaves a path to freedom, and Americans a road not taken in the tortured path to racial justice, is untenable. Slavery in the British Empire was just as horrific as in Britain’s former colonies, and the economics of enslavement and emancipation were similar. Enslaved people of the British West Indies made Britain wealthy, just as the enslaved people of the South made Americans wealthy. Absentee landlords of sugar plantations in Jamaica, Barbados and other British islands lavished their fortunes on English country estates, held seats in Parliament or controlled a contingent of those who did, and ensured that their interests were protected. They successfully resisted abolition for decades, just as slave owners resisted abolition in the United States.

The British did not abolish slavery in their empire earlier than the United States because they were more humane than Americans. The difference in timing was driven by the market. The power of the West Indian sugar interest declined precipitously along with the price of sugar in the 1820s, and the British Reform Act of 1832, which eliminated the rotten boroughs controlled by the West India Lobby, doomed their cause. Slavery was abolished in the empire in 1833—a remarkable achievement—though London gave its assent to labor laws that tied many former slaves to the land and limited emigration, substituting a life of harsh labor and peonage for slavery. Such laws, in various forms, limited opportunity and the enjoyment of fundamental rights for former slaves and their descendants in the British West Indies for more than a century. The scars of slavery are as pervasive in Barbados and Jamaica as they are in Mississippi.

In the United States, principled anti-slavery sentiment could not overcome the tobacco and rice planters’ dependence on slave labor and achieve the abolition of slavery in America during the Revolution or its aftermath, and this proved to be a tragedy of incalculable proportions that led to suffering and death for millions of African Americans for generations, and millions of white Americans in the Civil War. Despite growing repugnance for slavery, little effort was made to abolish slavery at a national level. Many Revolutionary leaders, whether slave owners like George Washington or James Madison or opponents of slavery like John Jay or Alexander Hamilton, believed that an attempt to end slavery by federal law would endanger the fragile union of the states. Benjamin Franklin was willing to risk that, and in his last public act, just two months before his death, he signed a petition asking Congress to abolish slavery in the United States.

Many of the others believed, or at least hoped, that the economy would outgrow slavery within a generation or two. Some thought that the abolition of the slave trade, ending the importation of more enslaved men and women from Africa and the Caribbean, would gradually suffocate the institution. This was wishful thinking that ignored the natural increase of slaves already in the country, but reliable quantitative information was scarce and men persuaded themselves that if no new slaves were brought into the United States, slavery would wither and die without political trauma. In any event, this half measure was the only restriction the wealthiest tobacco and rice planters would accept. It was to their advantage, because choking off the importation of new slaves would drive up the market value of their human property.

Washington and Madison both seem to have expected slavery to decline as the economy changed in the states where slaves were most numerous. Tobacco appeared to Washington and other observers like a staple crop without much future. Great fortunes were no longer built on tobacco. It exhausted the soil, and planters who grew it faced diminishing returns in a declining market. Washington abandoned tobacco for wheat, a crop for which slave labor was poorly suited. Other tobacco planters slid inexorably into debt (a fact apparently unfamiliar to Hannah-Jones, who wrote that the “dizzying profits” from slave labor led Thomas Jefferson and “the other founding fathers” to believe they could win a war with Britain). Demand for Carolina rice, much of which was shipped to the West Indies to feed the slaves on Britain’s sugar islands, was stable, but rice was restricted to tidewater lowlands and most of the marshy land suited to it was already in cultivation. Rice was wholly unsuited to the southern interior into which the population was moving. Hopeful men thought that new crops, new agricultural practices and commercial and industrial development would favor free labor and extinguish slavery without a struggle.

Persuaded, or at least hopeful, that the problem would resolve itself in time, and that slavery could be moved toward ultimate extinction by half measures, the Revolutionaries failed to imagine the horrors ahead. They did not imagine that cotton—a minor crop previously restricted, like rice, to a narrow coastal region—would race across the South and create a demand for enslaved people comparable only to the insatiable demand of the West Indian sugar plantations. Short-staple cotton suited to the vast southern interior was barely grown in the United States at the time of the Revolution. Picking the seeds out of it was too costly, even with slave labor, to make it profitable. The unexpected invention of a simple machine to remove the seeds made it profitable in bulk and doomed unborn generations to the brute labor of planting, cultivating and harvesting it. Growing demand for cheap textiles drove the mills of the industrial revolution. Producing cotton to feed those mills absorbed American lives like dry sand absorbs water and condemned African Americans to slavery and peonage that lasted until cotton production was mechanized in the third quarter of the twentieth century.

For all of the good the Revolutionaries did—securing our independence, creating the first modern republic, knitting together the fragile union and creating our national identity, and committing the new nation to ideals of liberty, equality, civil rights and citizenship based on the revolutionary implementation of the idea of natural rights—their failure to dismantle slavery will forever haunt their memory as it has stalked our history.

But it does not convict them of hypocrisy. Indeed, Hannah-Jones makes no effort to explain why a revolution she claims was founded on a desire to retain slave property should have, quite perversely, adopted a political philosophy of natural rights so utterly antithetical to slavery. That philosophy, after painful decades of political struggle and decades of human suffering, led to the abolition of slavery and to the drive to secure the personal liberty, legal equality and civil rights denied to African Americans. The revolutionary commitment to natural rights is, in the final analysis, the foundation upon which Hannah-Jones’ own outrage rests. She is the daughter, the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of black Americans denied their natural rights by people who embraced ideas wholly antithetical to the revolutionary ideal of universal natural rights—who perverted it into a theory of natural rights for a select few who tyrannized the many.

Thrown on the defensive by a theory of natural rights that challenged the foundations of the slave system, supporters of slavery in the second quarter of the nineteenth century resorted to pseudo-scientific arguments that blacks were not fully human, and therefore could be deprived of those rights that were the natural entitlement of those who were fully human. The rise of such thinking in America and around the world fostered the inhumanity of racial injustice and led to unspeakable horror in the twentieth century, including abominable crimes against individuals as well as acts of genocide perpetrated around the globe on a grotesque and immense scale. We have not yet crushed the last embers of this thought.

The American Revolution did not perpetuate racial hatred and oppression. It challenged a world that was profoundly unfree. The principle of natural rights asserted by the Revolution led ultimately to the overthrow of slavery and now challenges every form of oppression, exploitation, bigotry and injustice. The American Revolution was the most important moment in modern history, and its ideals are the still the last, best hope of our world, where too many are still denied their natural rights.

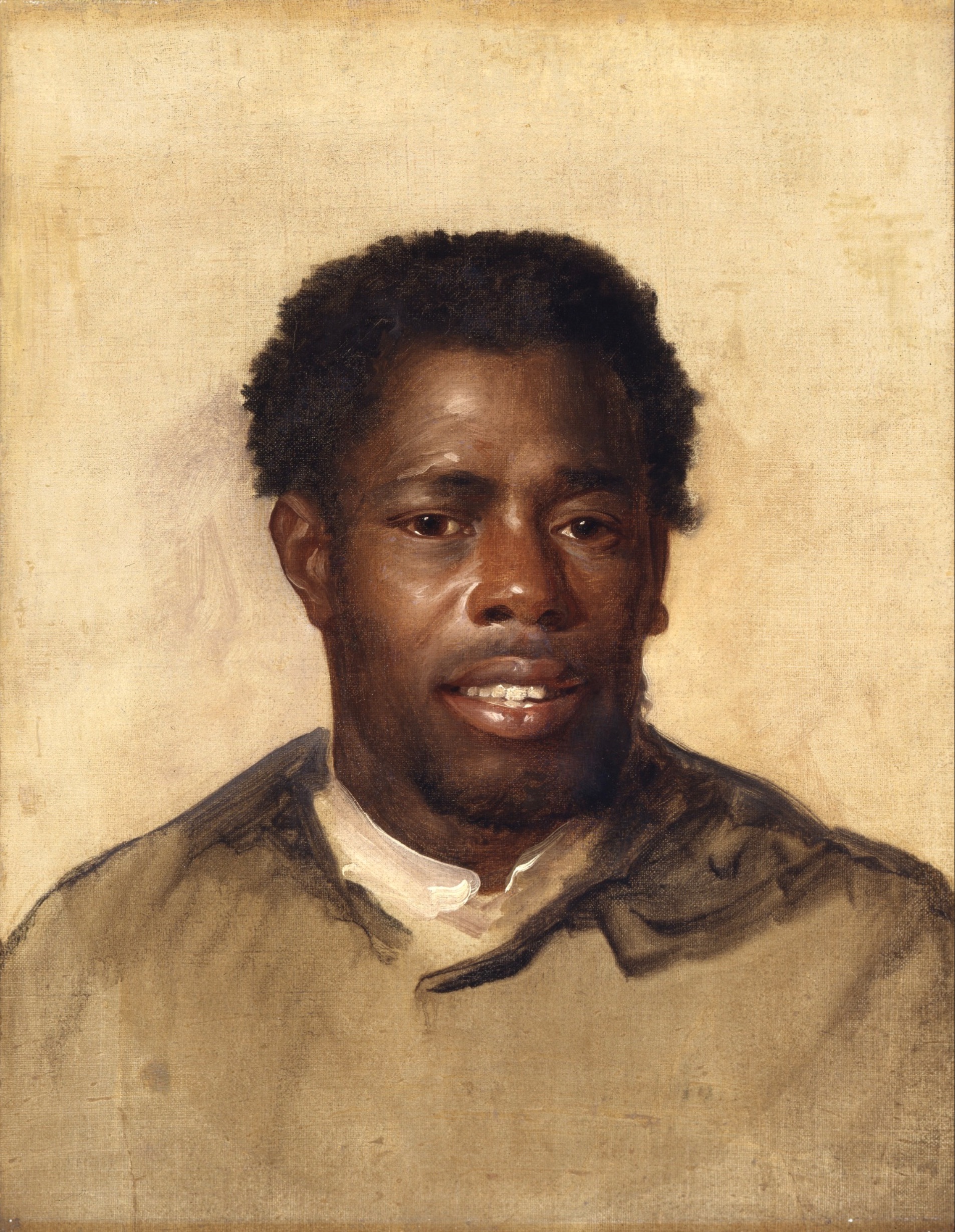

Above: American-born artist John Singleton Copley painted this portrait of an unidentified man in London about 1778. Unlike most eighteenth-century American and European portrayals of men and women of African descent, it captures the individuality of the sitter. Detroit Institute of Arts.

We encourage all our visitors to read Why the American Revolution Matters, our basic statement about the importance of the American Revolution. It outlines what every American should understand about the central event in American history. It will take you less than five minutes to read—and a few seconds to send the link to your friends, family, and colleagues so they can read it, too.

Read the companion essays responding to the 1619 Project: “The American Revolution and the Foundations Free Society” and “What’s Wrong with ‘The Idea of America’?”