Ralph Waldo Emerson composed the Concord Hymn to be sung at the dedication of a simple memorial beside the Old North Bridge at Concord, where patriot militia had faced the British on the morning of April 19, 1775:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

Emerson and his audience, gathered on July 4, 1837, believed that the Revolution that began that day had started a revolution in human affairs that would reach around the world and would ultimately free the human race from the yoke of tyranny and oppression under which it had labored for thousands of years.

They believed that the United States was an exceptional nation. They were under no illusion that it was a perfect one, but they believed the fulfillment of its ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights and responsible citizenship had a fair chance of making it as close to perfect as human energy and imagination could achieve.

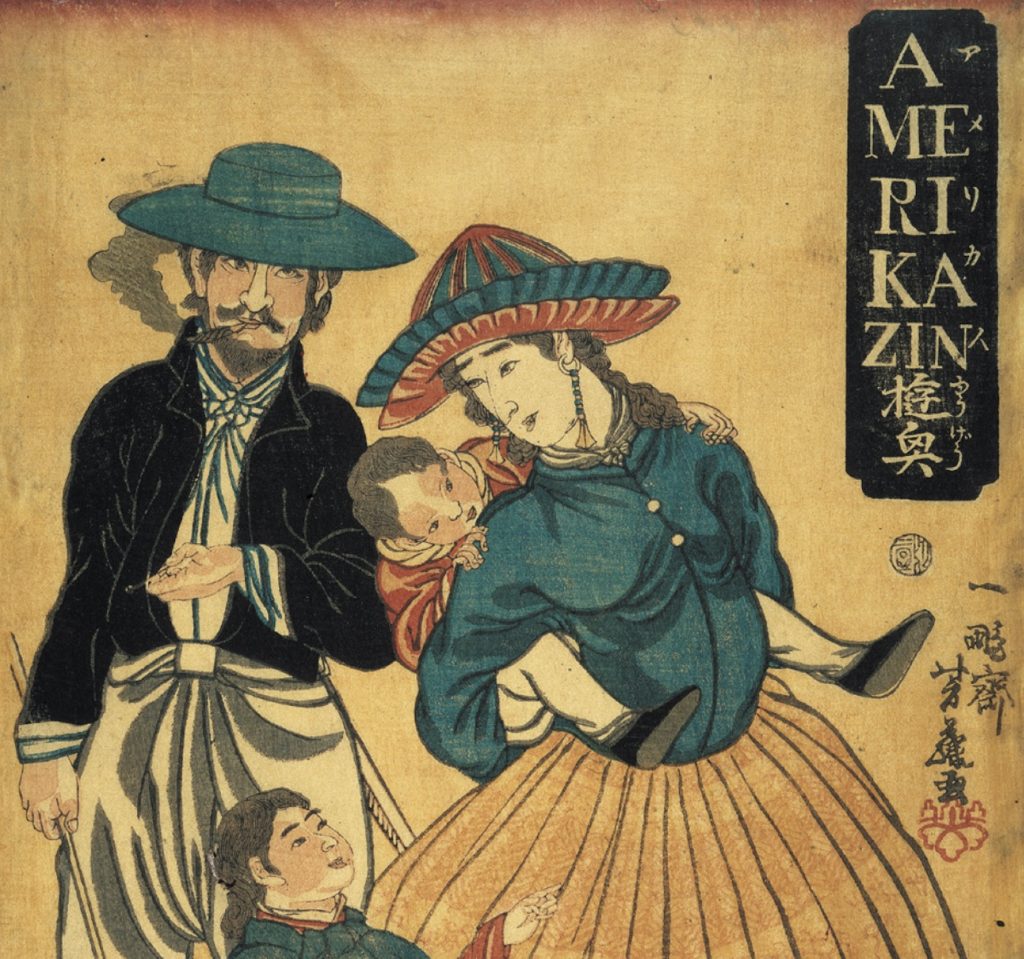

The United States certainly was an exception, even in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the family of nations. It was a republic—a nation dedicated to the interests of ordinary people—in a world dominated by monarchies. We are reminded just how unusual the United States was in Emerson’s generation by the way the United States and its revolution was then perceived on the other side of the world.

A few weeks after the ceremony in Concord, an unarmed American merchant ship, the Morrison, sailed into Tokyo Bay. The captain aimed to return seven shipwrecked Japanese sailors he had picked up in Macau, deliver a group of Christian missionaries and engage in trade. The Japanese fired on the Morrison, driving the Americans away—but it was easier to drive off foreign vessels than it was to keep foreign ideas out of Japan. Despite official edicts to prevent contact with the outside world, information about the West and about the United States and even the American Revolution had begun to reach Japan—about as remote from Concord’s Old North Bridge as any place on Earth.

Japan had been closed to nearly all Westerners for more than two hundred years. This policy of sakoku, or “closed country,” was intended to prevent foreign missionaries and colonial powers from undermining the authority of the ruling shogunate. But even during that period of self-imposed isolation, the Japanese learned some of what was going on in the West, chiefly from European books brought to Japan by Dutch traders permitted to call at Dejima, a tiny artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki, which was the sole point of legal contact between Japan and the West. The Japanese called this body of knowledge rangaku, literally “Dutch knowledge,” but it included information from other Western countries.

Rangaku included immense amount of scientific and technical knowledge, including Western advances in biology and physics. The Japanese learned about discoveries in chemistry and were fascinated by telescopes and microscopes, Western medicine, surveying and cartography, clockwork mechanisms, hydraulics and steam engines. They were particularly intrigued by electrical generation. The first practical Japanese book on this subject, Hashimoto Soukichi’s Oranda shisei erekiteru kyūri-gen, published in 1811, included a description of Benjamin Franklin’s experiments with electricity.

Aware that they were living in a world of predatory imperial powers, rangaku scholars tried to learn as much as they could about Western nations, Western customs and most of all about the military strength of the powers whose ships were arriving off their islands in increasing numbers. Curiosity about the West led them to inquire about the United States and its unusual form of government.

The Japanese had learned about North America, at first as a wild, mostly unsettled land peopled mainly by primitive people who wore skins and feathers, from the Dutch in the seventeenth century. They also learned that the British had settled in North America, but the news that Britain’s American colonists had staged a revolution and secured their independence from Britain did not reach Japan until after 1800.

Rangaku scholar Mitsukuri Shōgo provided what might have been the first Japanese account of the American Revolution in his Konyo zushiki (An Overview of the Geography of the World), published in 1845-1847:

During our Hōreki period England was at war for some years. The people became sorely enfeebled, and the loss in foreign trade was not at all inconsiderable. The English sought, therefore, to employ the people of this land, and use them for their own ends. The people of this land, however, resented their abusive language and scorned their cheap wages, and refused to obey their orders. They even seized and threw into the sea 242 boxes of tea that had been brought from India by the English. In great wrath, the English dispatched a number of warships, and blockaded the most important port of this land, thus stopping the transit of provisions into the country. The people found themselves in most desperate straits, and officials of the thirteen states assembled to ponder the situation. A military official named Washington, and a civil official named Franklin, promptly stood up and declared, “We must not lose this heaven-sent opportunity. We must sever relations with the English forever.” The assembly decided to adopt this proposal.

The English then realized that they could not attain their ends, and that their words had been unreasonable, so they lifted the blockade and departed. In 1780, a certain official of this land reached an agreement with the English that this should forever be a free and independent nation. Since then, the nation’s strength has steadily increased, and its territory has expanded tremendously.

Having left the Revolutionary War entirely out of this brief account, Mitsukuri filled in the gap by including in his atlas a brief biography of George Washington, undoubtedly the first account of Washington’s life published in Japan. Mitsukuri identified Washington as the son of a “big farmer” in Virginia and told the story of his service in the French and Indian War, his successful conduct of the Revolutionary War and his service as “High Official” at the head of the new American government for eight years. Mitsukuri repeated errors that were probably in his Dutch sources, mistakenly dating Washington’s birth in 1734, for example, and reporting that Washington was educated at a school in Williamsburg, but the general outline of his account is as accurate as short accounts of Washington’s life published in Europe in the early nineteenth century.

The George Washington Mitsukuri described sounds much like a virtuous Japanese lord. When events “caused the colonists in North America to hate their mother-country,” he explained, “Washington voluntarily used his wealth to equip troops.” Washington was a strict disciplinarian, but he cared for the welfare of his soldiers and led them with courage. Washington was prudent and cautious, but took advantage of each “favorable opportunity” and “crushed Hessian troops at Trenton, and defeated an English general at Princeton.” As the war continued, “the aggressive power of the American forces became greatly enhanced, bringing fear to the English, and winning renown throughout the world.” Final victory was won at Yorktown, Mitsukuri wrote. “All this was due to Washington’s great ability.” Patient, skillful and brave, Washington had “gradually saved the country from its peril, and established peace and order.”

The nature of that order was hard for Mitsukuri to explain. When he came across the word “republic” in his Dutch sources he was hard pressed to translate the concept into Japanese. When he looked it up in a Dutch dictionary, he learned that a republic was a form of government without a monarch, which was wholly alien to the Japanese experience. A rangaku colleague, Ōtsuki Bankei, suggested that he translate it as kyōwa, a Japanese word applied to the Gonghe Regency (841-828 BC), a period of Chinese history in which two dukes ruled in the place of a dissolute king who had been driven from his throne. The connotation is joint, or cooperative, harmony, rather than a form of government in which the public good, as opposed to the interests of a monarch or a ruling group, is the primary end of government. The Chinese equivalent, gonghe, ultimately became the modern Chinese word for republic. Kyōwa remains the Japanese word for republic—a word and an idea introduced by a Japanese scholar trying to make sense of George Washington and his revolution.

Emerson and his audience would have been mildly chagrined to learn that the first detailed treatment of the American Revolution published on the other side of the world located the first great battle of the Revolutionary War in Lexington rather than their own Concord, but they would not have been surprised that the American struggle for liberty and the universal rights of mankind had attracted notice in the most isolated nation on Earth. They were proud of the American Revolution and the exceptional nation it had created, and believed that the shots fired on April 19, 1775, would awaken the world. So they have.

Above: Detail from Yoshifuji Utagawa, Amerikajin yūgyō [American family out for a stroll] (Yokohama, Japan: Soto, 1860), Library of Congress.

We encourage all our visitors to read Why the American Revolution Matters, our basic statement about the importance of the American Revolution. It outlines what every American should understand about the central event in American history—our shot heard round the world. It will take you less than five minutes to read—and a few seconds to send the link to your friends, family and colleagues so they can read it, too.

If you share our concern about ensuring that all Americans understand and appreciate the constructive achievements of the American Revolution we invite you to join our movement. Sign up for news and notices from the American Revolution Institute. It costs nothing to express your commitment to thoughtful, responsible, balanced, non-partisan history education.