Liberty is commonly depicted as a pretty young woman in a white classical robe, kindly in peacetime, steel eyed and determined in war. This personification of Liberty is grounded in Roman depictions of the goddess Libertas, who was honored with a temple on the Aventine Hill in Rome. Libertas was often depicted offering a pileus, the soft cap that symbolized freedom for former slaves, and was sometimes shown wielding a vindicta, a rod symbolizing emancipation from slavery, tyranny and arbitrary rule.

These symbols—the pileus and the vindicta—intertwined with the initials U.S., were cast into the breech of cannon barrels manufactured in Philadelphia in 1777, a silent acknowledgment of the hard truth that American liberty had to be won in battle and protected by arms. One of these cannon barrels, a chance survival from a desperate time in the Revolutionary War, is on display at the headquarters of the American Revolution Institute. It was probably cast in the summer of 1777 by James Byers, who set up a makeshift foundry in a converted pottery workshop.

At the moment Byers cast it, and probably no more than a few blocks away, a remarkable young woman was suffering. Her story, like the hard truth symbolized by the emblems of liberty cast into the cannon barrel, reminds us that liberty is hard to win and hard to keep, and might be better personified by a woman in a tattered skirt and a torn shirt, her face black from burnt powder, her hands dirty and bloodstained, her expression angry, defiant and determined.

The young woman’s name was Margaret Corbin. She was then not quite twenty-six years old. Margaret had been born in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania, in the rolling farm country west of Gettysburg, though that blood-soaked town would not be founded until she was ten. Her father (and her mother, too, probably, though we don’t know that for sure) was a Scots-Irish immigrant. They settled on the Pennsylvania frontier not long before Margaret was born—two of the thousands of poor immigrants who surged into the Cumberland Valley in the last decades before the Revolutionary War, many of whom moved south into the Great Valley of Virginia and into the western Carolinas.

Margaret barely knew her parents. When she was five, her father was killed by Indians and her mother taken captive, never to be heard from again. Margaret and her brother weren’t home when the Indians attacked, and as frontier orphans they were raised by an uncle. Margaret married a farmer, John Corbin, when she was twenty-one.

Some three years later he enlisted in the First Company of Pennsylvania Artillery. What could have moved him to do it? What did fighting the British mean to him? We cannot know for sure. We can only generalize. Men like John Corbin did not read treatises on natural rights or political economy. Few of them had ever heard of John Locke or Baron Montesquieu or ancients like Cicero. Taxes on paint, paper, lead, tea and glass—the Townshend Duties that so angered colonial merchants—didn’t touch people like Corbin, who didn’t buy paint or drink tea, who didn’t use much paper, and for whom lead was something cast into musket balls rather than holding genteel window glass in place.

Men who lived in the colonial backcountry valued their independence. They had little property. In Pennsylvania, where the law was more generous to squatters than in other colonies, many lived on land to which they had no clear title. What little they had—a bedstead, a few pots, a gun—belonged to them, and there was no squire to whom they owed obedience nor to whom they paid rent. And if they liked they could go, joining the constant movement southward through the valley, or press westward, toward the Ohio frontier, where the British had drawn a line forbidding settlement—a symbol of their intention, or so it seemed to Americans across the colonies and up and down the social scale, to impose much tighter control on their restless, unruly subjects.

Margaret went with him to the army. Like thousands of other women who followed the army, she probably had nowhere else to go, and supported herself doing laundry, mending clothes, cooking and nursing the sick. George Washington didn’t like the practice, but grudgingly accepted it, and allowed women with the army to draw rations, at least when his men were in camp. When his troops were on the march, he did his best to shed the army of anything that would slow it down or consume its meager stores, but at every moment of the war, women were present—in camp, on the march and on the battlefield. This was particularly true of the artillery, which had wagons and horses and, on the battlefield, a constant need for people to carry ammunition, powder and water to swab and cool the guns between rounds, without which powder being loaded would explode prematurely and kill or maim their crews.

Margaret went with the First Company of Pennsylvania Artillery to the defense of New York City. What she did between August and November 1776 is a blur, as Washington’s army shifted from Long Island to Manhattan to Westchester County, parrying the blows of a superior British army intent on destroying it.

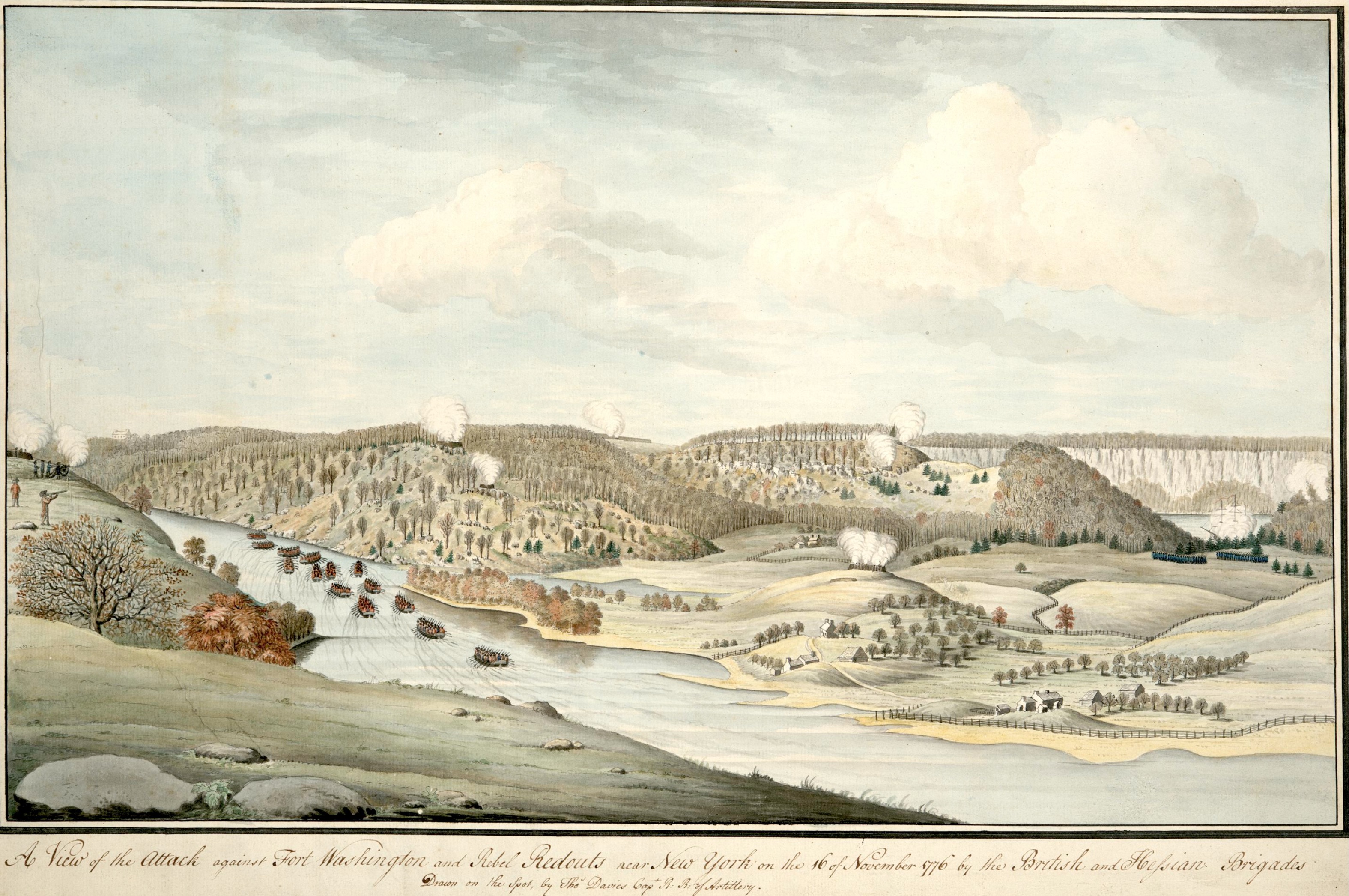

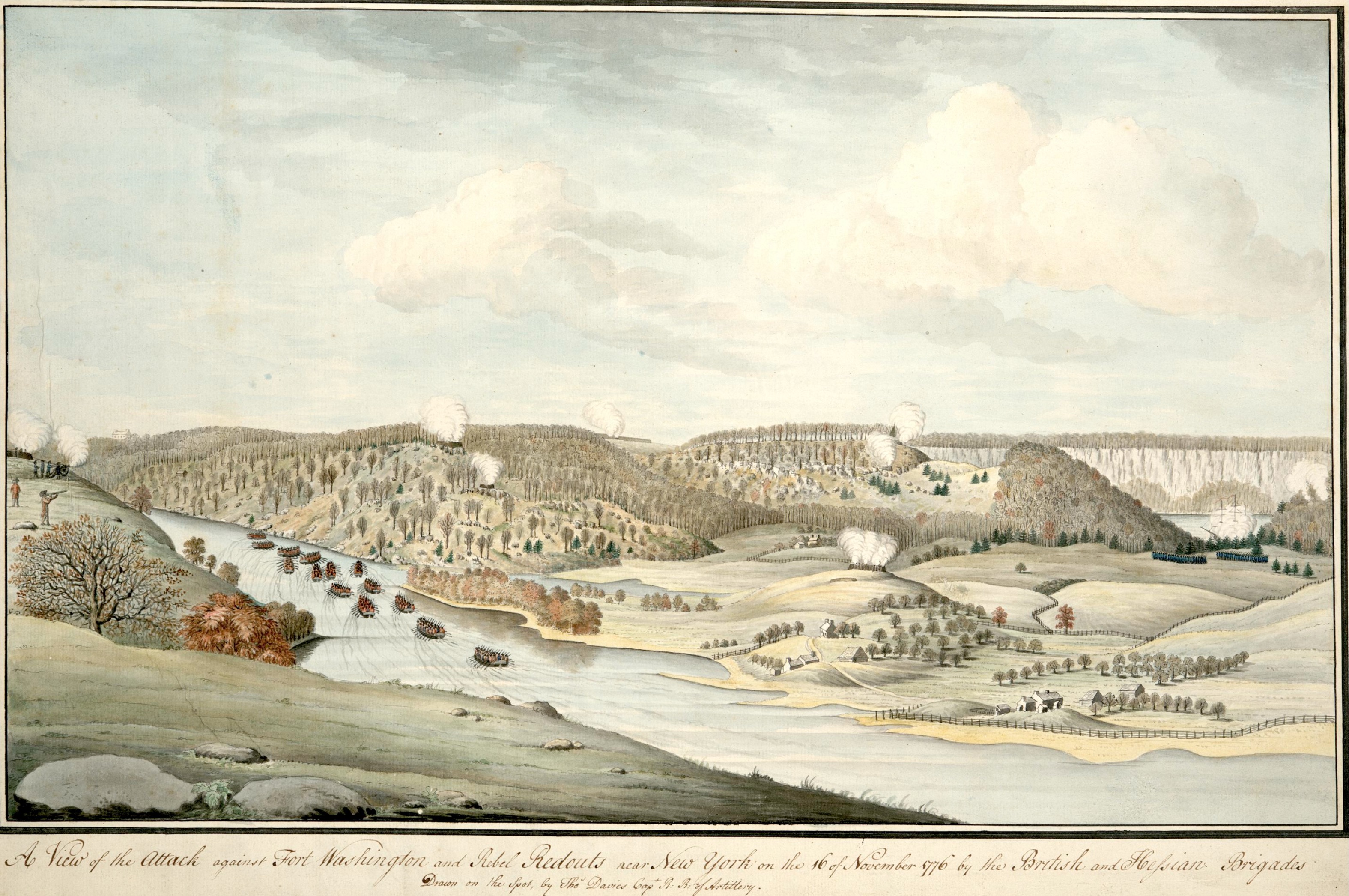

On November 16, 1776, their battery was stationed north of Fort Washington, on the northern end of Manhattan. The guns were set up on the northern edge of a vast ridge, which the British and their Hessian auxiliaries had to take before approaching Fort Washington—the last American stronghold on Manhattan Island. The battery supported some 250 Maryland and Virginia riflemen commanded by a skilled young Marylander named Moses Rawlings.

A British officer, Thomas Davies, painted a watercolor (now owned by the New York Public Library) of the approach from a secure vantage point across the Harlem River, depicting the British landing on northern Manhattan. One of their batteries is firing in the middle foreground, and in the middle distance, on the edge of a ridge, smoke rises from an unseen American battery perched on the edge of the ridge defying the enemy’s approach. Fort Washington—a large, crude pentagonal earthwork—is in the distance, a long way from the outwork where the little battery was firing.

The puff of smoke from the lonely American battery in this watercolor is as close as we can come to an image of Margaret Corbin, who was on hand to support the guns. John Corbin was a matross—a key member of a conventional gun crew, which in theory consisted of a loader, a spongeman, a ventsman, a senior gunner and a firer. Under usual circumstances, a matross could assume any of these roles except that of senior gunner, which required more training than most men received, and in a crisis a matross might wind up commanding a gun. A gun battery in the field also had a large contingent of laborers to drag the heavy guns around, move powder and ammunition from wagons in the rear, and carry water from wherever it might be found—sometimes at a considerable distance from a firing position. Women often did this work.

Everyone on a gun crew had a very specific role in the deadly choreography of battle. The loader placed the powder bag in the bore and the spongeman rammed it home with the back end of the sponge staff. The ventsman, who had been keeping his leather-covered thumb over the vent hole to keep fresh oxygen from feeding a spark, jammed a tool like an icepick through the hole to tear open the powder bag. The loader then added the ball and the spongeman rammed wadding in behind it. The senior gunner (typically in command) aimed the piece and the ventsman primed it by pouring fine priming powder down the vent. Everyone stepped back but the firer, who touched off the priming charge with a slow burning match held in a tool called a linstock, discharging the gun.

The deadly dance started again with the spongeman dipping his sponge staff into a bucket of water and swabbing out the gun to extinguish lingering sparks. If he didn’t get them all, the next powder charge might blow as he rammed it home. Pension records testify to the many spongemen who were burnt, blinded, maimed or killed outright by premature powder explosions. It was the most dangerous job on a gun crew.

John Corbin may have been a spongeman. As the Hessians advanced on their position, he was killed by Hessian musket fire, an enemy artillery round or the premature explosion of powder in his own gun. We will never know which. What we know is that Margaret was nearby and took his place on the gun crew, which continued firing. We can only imagine the scene, but if she was carrying water and her dead husband was a spongeman we can picture her seizing the sponge, dipping it in the water she had brought forward to swab it out. The enemy brought its own light cannons forward as the infantry approached, and as soon as they were close enough they undoubtedly shifted from heavy round shot to grape shot or canister—ammunition that scattered balls like a shotgun.

Margaret fell hideously wounded before the battery was overrun, hit in her left shoulder and arm, jaw and left breast. She must have been looking down, her chin briefly on her chest near her armpit, her left arm raised. In that posture a ball entering her left arm near the shoulder could have smashed her jawbone and lodged in her left breast, or even passed through her breast and onward in flight. Whether the wound was caused by musket or cannon fire we don’t know, but the damage was severe. Margaret was captured, though in so much pain, if she was conscious, that she can hardly have cared about falling into the hands of the enemy.

Fort Washington was supposed to hold out for weeks, but it fell within a hour and the British captured over 2,800 Americans and much of the Continental Army’s remaining cannons, powder and ammunition. Three-fourths of those men would later die as prisoners. George Washington watched, appalled, from the New Jersey side of the Hudson. It was the worst defeat he ever suffered, though he suffered at a distance. Margaret’s suffering was much more immediate. The British released her, along with other women and some of the wounded. She was taken overland by wagon to Philadelphia, where she languished for months, slowly recovering, at least somewhat, from her wounds.

She was evacuated from Philadelphia before it fell to the British in the fall of 1777 and ultimately assigned to the Corps of Invalids, a unit composed of disabled soldiers kept on the army’s rolls to guard hospitals, magazines and other facilities—soldiers unable to march or bear the strains of campaigning, with no other means of support. Margaret’s place among them was an anomaly. She was apparently too crippled by her wounds to do any service, but she was housed, drew rations, provided with rough clothing, and cared for as she recovered, to the extent she ever did.

On July 6, 1779, Congress awarded Margaret Corbin, “who was wounded and disabled in the attack on Fort Washington, whilst she heroically filled the post of her husband who was killed by her side,” a complete outfit of clothing and one-half of the pay of a private soldier for the rest of her life. By this act Congress formally recognized a female combat veteran for the first time in American history. George Washington’s aide Tench Tilighman wrote to Henry Knox’s aide Samuel Shaw and paid Margaret a fellow soldier’s grim compliment: “It appears clearly to me that the order forbidding the issue of Rum to Women does not extend to Mrs. Corbin—Granting provision at all, to Women who are followers of the Army, is altogether matter of courtesy, and therefore the commanding General may allow them such a Ration as he thinks proper—But Mrs. Corbin is a pensioner of Congress.” Therefore, he added, she should be given rum with her rations, but “perhaps it would not be prudent to give them to her all in liquor.”

In 1780, she moved with the Invalid Corps to West Point, where she remained a disabled pensioner in the charge of William Price, commissary of military stores, long after the war was over. On January 31, 1786, Price complained to Henry Knox, who was then secretary of war. “I am at loss what to do with Capt Molly” he wrote. “She is first an offensive person that people are unwilling to take her in charge . . . and I cannot find any that is willing to keep her.” She was, we can only imagine, in constant pain from her wounds. If she was offensive, we can readily understand why. William Price comes off rather badly in the story. Margaret Corbin—“Captain Molly”—never left West Point, and died there in 1800, just forty-eight, and was buried in a grave that has been lost to memory.

She paid the cost of liberty, and in doing so lost the personal independence she was probably fighting to maintain, or secure for herself, her husband and for the family she never had. Her arm crippled, her face disfigured, she is not the way we imagine Liberty. Perhaps we should.

Margaret Corbin is one of many remarkable veterans of the Revolutionary War featured in our current exhibition, America’s First Veterans, on view at the headquarters of the American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati through November 29, 2020. Learn more about America’s First Veterans.