With the Revolutionary War finally over, Benjamin Lincoln returned home to Hingham, Massachusetts. He had left in 1776, a stout and sturdy farmer of forty-three, respected in his community but little known beyond. He returned a major general. He had helped force the surrender of one army, surrendered one himself, and accepted the surrender of another, and had served the new nation as secretary at war. He walked into his home in November 1783—a house that had sheltered three generations of Lincolns before him—with a permanent, painful limp from an ankle shattered in combat. He was fifty years old, and one of the most famous men in America.

Charles van Hogendorp, a young nobleman attached to the Dutch ambassador, visited Lincoln and his wife, Mary, a month later. “Imagine the effect on me of his noble simplicity,” the young man wrote, “when, during the evening, sitting in front of the fire, Lincoln spoke to us, smiling all the while, ‘I lived here for twenty years after my marriage and never dreamed of war. Here is my place, and here is that of Mrs. Lincoln’s, and it’s here that we pass our evenings talking together.”

At his fireside, Benjamin Lincoln considered the fate of the republican experiment for which he had sacrificed and suffered. He was a moderate in an age of passion and ideological tension—a thoughtful revolutionary, devoted to the cause of independence, republican government, and the ideals of liberty, equality and citizenship. He found these values expressed in the everyday life of his community. He had fought for the independence of the United States, but it was personal independence and the independence of his community that he most cherished. He had risked his life to defend republican governments in the independent states, but it was the little commonwealth of family, town and region that mattered most to him. A hero of the Revolution, he preferred his fireside to public life.

Benjamin Lincoln was, in many ways, an improbable sort of Revolutionary hero. The most remarkable thing about his life before the Revolution was how ordinary it was—how it fell into the pattern of provincial New England life that was already more than a century old when Lincoln was born. Lincoln’s father, the elder Benjamin, was one of Hingham’s leading men—colonel of the local militia and a member of the governor’s council. The younger Benjamin was an adjutant in his father’s regiment, town clerk, and from 1765, a town selectman. His father died in 1771, and the next year the younger Benjamin was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the regiment and elected to the colonial assembly.

There he reflected the stubborn independence of provincial New England. For all their conventional expressions of respect for the king, Lincoln and the Massachusetts men and women of his generation were the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of religious radicals who had very deliberately placed an ocean between themselves and Old England. They were proud of their autonomy—their independence within the British Empire—and when the king’s ministers sent an army to occupy Boston and compel obedience to the crown, their outward respect for the king and his ministers disappeared very quickly. The old radical spirit of Puritan dissent, partly secularized but no less fierce and unyielding, resurfaced.

When Gov. Thomas Gage dissolved the assembly in 1774, Lincoln was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and led preparations for war. After Lexington and Concord he was elected to the executive council, which exercised government authority outside British-held Boston. Although he had no experience commanding men in the field, he was promoted to major general of the Massachusetts militia in January 1776 and went to work organizing coastal defenses, preparing for the possibility of British raids on exposed ports. In September 1776 he was given command of a militia brigade sent to join Washington’s army at New York. At Washington’s urging, Congress appointed Lincoln a major general in the Continental Army in February 1777.

In the course of something like thirty months, he had gone from being a prosperous, solid, unassuming Hingham farmer to a leader in a continental war against Britain for the independence of the United States of America. The war found him, and revealed a reservoir of skills, strength and courage few people—perhaps even Lincoln himself—imagined he possessed. He joined Washington’s army in New Jersey and was a calm, methodical and tireless organizer in an army in constant need of such skills. He also proved fearless under fire, a quality Washington valued.

In the summer Washington sent him north to the army facing Burgoyne’s march toward Albany, expecting Lincoln’s presence to stiffen the resolve of Massachusetts militia. Given a largely independent command threatening Burgoyne’s left, Lincoln contained the British from the east side of the Hudson while the climactic battles of the Saratoga campaign were fought across the river. As the Americans pulled the net tight around Burgoyne’s army, Lincoln was wounded—his ankle shattered by a British musket ball. Doctors saved his leg, but it was two inches shorter than the other and he walked with a limp for the rest of his life.

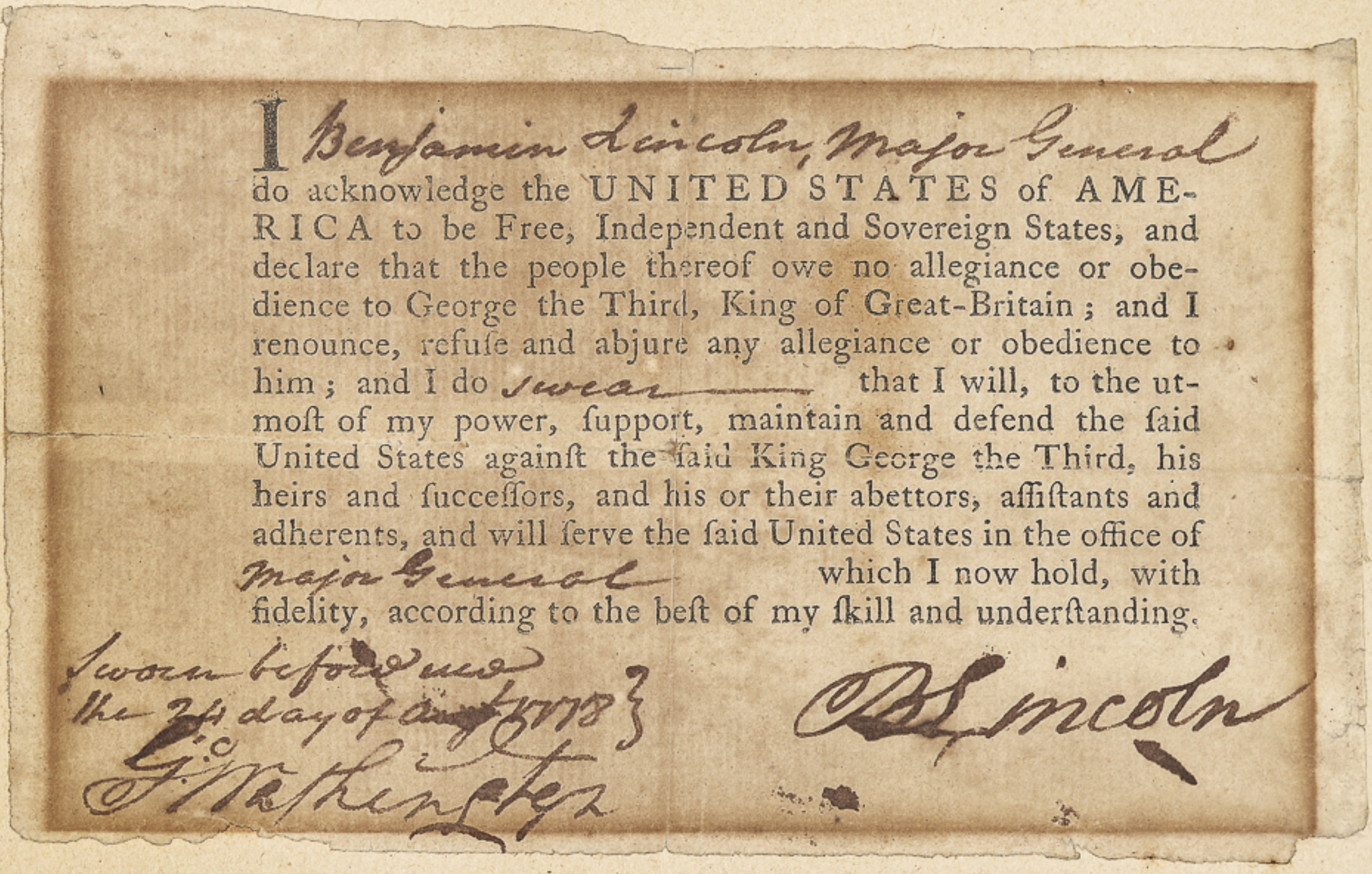

After months of painful recovery, Lincoln rejoined Washington’s army in August 1778. He certainly didn’t have to. Officers had retired with far less debilitating injuries, but Lincoln was not like them. He had made a commitment to himself, if not to his God and to the republic, to see the war through. When he arrived at Valley Forge, the commander-in-chief administered the oath of allegiance to the United States that Congress had prescribed months earlier, when Lincoln was recovering. He was the last of Washington’s generals to sign the oath, and we can be certain Washington witnessed Lincoln’s signature with admiration.

Each officer signed two copies of the oath of allegiance, one of which was sent to Congress. The other was retained by the signer. The copies sent to Congress are now in the National Archives. Lincoln’s retained copy, seen here, is in a private collection. The Institute collections include a rare blank form with the oath printed twice.

American national identity was forged in moments like that one, as men of different backgrounds, regions, and experiences—men who, in the absence of that war, would never have met nor had any reason to admire one another, much less to become friends—demonstrated their commitment to a common cause.

Two months later Congress ordered Lincoln to take command of operations in the Carolinas and Georgia. Lincoln’s modern biographer, David Mattern, compares the decision to the appointment of Washington, a Virginian, to command the army outside Boston in 1775—sending a New England general to the South signaled that its defense was a continental, and not just a regional, concern. Lincoln had a reputation as an effective organizer, able to manage difficult situations and people with tact. He had earned a share of the credit for Saratoga but had played no part in the unseemly maneuvers of Horatio Gates and his allies to displace Washington in the afterglow of that victory. He had organized coastal defenses in Massachusetts, experience relevant to the exposed situation of the Georgia and Carolina coasts. Despite his limited experience in combat, he was a logical choice for the assignment.

Almost no one was expecting a major British invasion of the region. Indeed Congress directed Lincoln, if it proved practical, to invade East Florida and take British-held St. Augustine—a suggestion Lincoln soon discovered was based on a total misunderstanding of the situation. There were fewer men available for service in the region than Congress believed. Supplies and money were inadequate to mount an effective defense, and when the British struck—first Savannah, then Charleston—Lincoln’s army was inadequate to meet the challenge. In 1780 his army—2,200 Continentals and some 500 militia—was trapped in fortified lines in Charleston, South Carolina, and forced to surrender. He had mounted what Abigail Adams called “a gallant defence” and had earned the gratitude of South Carolina’s civilian authorities, but the outcome of the campaign was humiliating.

Lincoln was paroled and reported to Congress in Philadelphia, then returned home to Hingham after two years’ absence. His children were growing up without the daily presence of a father, and Mary was struggling to run the farm alone. He devoted most of that winter and spring to his home and family, but as soon as he was exchanged Lincoln returned to Washington’s army. In July 1781, barely two weeks after reporting to camp, Lincoln led eight hundred men on an expedition to probe British defenses on Manhattan. The defeat at Charleston had not shaken Washington’s confidence in Lincoln.

A few weeks later Washington chose Lincoln to lead the army south to attack Cornwallis at Yorktown. “The success of our enterprize depends upon the celerity of our Movements,” Washington wrote, warning against delay. Any number of things might have gone wrong. None of them did, largely because Benjamin Lincoln managed the movement, ensuring that the men had proper camps and sufficient food, that straggling was discouraged and the army maintained a rapid pace. Washington met Lincoln near Williamsburg, Virginia, on September 23, and expressed his pleasure at finding the troops “in much better condition and with much less loss than could be expected.”

In the siege that followed, Lincoln held a post of honor, and personally led the men who opened the first parallel on the night of October 7, 1781. Ten days later the British asked for surrender terms, and on October 19 the British army marched out to lay down their arms. Cornwallis feigned illness and sent his second-in-command, Charles O’Hara, to relinquish his sword. Washington directed O’Hara to his own second-in-command, Benjamin Lincoln, who received the surrender and directed the British troops to an open field, where they grounded their arms and turned over their battle flags.

After Yorktown, Congress called on Lincoln to serve as the first “secretary at war.” Congress had finally concluded that congressional committees were wholly inadequate to carry out the executive responsibilities involved in supporting an army in the field. The choice fell on Lincoln, not because he was brilliant or politically connected, but because he was orderly, industrious and incorruptible. He respected the subordination of the army to civilian control and was highly regarded in the army and above all, by the commander-in-chief. For the next two years he worked to keep the army properly fed, supplied, and whenever possible, paid. He brought order and regularity to military administration, working to keep an army in the field and pressure on the British to end the war. It was thankless work and little remembered today, but it was essential work and Lincoln did it well.

When his services were no longer needed he resigned in relief and rode for home. He reached Hingham in early November. The family farm, despite Mary’s best efforts, was neglected and unproductive. Unable to walk without pain in an ankle that had never properly healed, he knew that returning to the life of a plain New England farmer was out of the question. The war had simultaneously made him one of the leading men in the country and deprived him of the ability he had long relied on to support himself and his family.

Like most veterans of the Revolutionary War, Lincoln returned home with little more than promises. His back pay had been tendered to him in Continental securities—wartime bonds that were circulating at less than a third of their face value. He could sell them, he knew, but at what he called “their present depreciated value” his losses would be catastrophic, and he would be left to “wade through the remainder of life with accumulated distresses.” Most veterans had no option, and sold their securities for what they would bring.

Lincoln had the advantage of having made wealthy acquaintances during the war, from whom he borrowed enough to make a new start. He mortgaged his real estate, built a flour mill on the eastern edge of Hingham, and was soon selling his flour in Boston. He expanded his operation, buying sloops to carry lumber to Virginia. With the proceeds he bought wheat grown on Virginia and Maryland farms and milled it into flour in Hingham. He added new land to his farm and invested in land in Maine—then the frontier of Massachusetts. Applying the management skills he had developed as a general and secretary at war to business, he made the commercial firm of Lincoln and Sons a modest success.

Reflecting on the world beyond his comfortable fireside, Lincoln believed that the political unity required to sustain a republic need not extend beyond the various regions. “The United States, as they are called,” he wrote, “seem to be little more than a name. They are not really embarked in the same bottom,” he added, using a ship owner’s metaphor. He doubted that “these States will, or ever can, be governed, and all enjoy equal advantages, by laws which have a general operation” and he doubted that such a government could be republican in character. He believed the sort of coercive power that Congress needed to address the nation’s economic problems and ensure its defense in a world of predatory powers would inevitably endanger “our republic ideas” by producing a centralized state in which power would be wielded by a distant national government, unaware of, and unresponsive to, the needs Lincoln saw in his own community.

Although he had seen the weakness of the Continental government up close as secretary at war, Lincoln was prepared to accept an even looser confederation in order to preserve the republican character of Hingham and of New England that he so cherished. The clashing interests and discordant nature of the different parts of the country weighed on him. The presence of slavery, in particular, seemed to him an insurmountable difference between the regions. Lincoln had enslaved a few people before the war, managing them much as he managed his white farmhands and domestic servants, but he had been shocked by the treatment of slaves in South Carolina and Georgia, leading him to utterly renounce what he called “the unjustifiable and wicked practice” of slavery. By 1783 the only enslaved person in his household was a woman named Flora, who was then in her eighties and incapable of supporting herself by her own labor. She died in 1789.

Slavery, Lincoln believed, made the South “feeble and defenseless,” because it made it a region of large plantations rather than of farms owned and worked by yeoman farmers, depriving the southern states of the kind of independent freeholders who had a stake in the independent, republican character of New England. The interests of the regions would inevitably clash, he thought, because “of our difference of climate, Productions, views &c.”

Lincoln concluded that the only feasible way to preserve the republican character of his own community was by breaking the continental Confederation into regional ones joined by alliances for common defense but otherwise independently governed. A truly national government, he was convinced, would have to have the power to tax and the power to compel obedience. The resulting government would involve a standing national army, national laws and national courts, and a growing class of national office holders loyal to the central government and intent on increasing its power.

In February 1784 Lincoln rode to Boston to preside over the first meeting of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati. He had been elected president by a meeting of officers held in the Continental Army camp in New York in the summer of 1783, before they dispersed. The Massachusetts Society was the largest of the thirteen state organizations that constituted the Society of the Cincinnati. The state societies were bound together in a confederation of fellowship and shared principles rather than by national power. For Lincoln, who remained president of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati for the rest of his life, the Society reflected the ideals for which he had fought—personal independence, local and regional autonomy and shared republican principles, along with a determination to cherish and promote the memory of the Revolutionary accomplishment.

Lincoln’s reflections were disturbed by the consequences of the severe economic downturn that gripped New England in 1786. Farm prices dropped and the credit upon which the post-war revival in farming and trade were built dried up. “We are drained of our cash,” he wrote, “our trade is embarrassed and our finances deranged.” Boston merchants and other large-scale creditors with their own notes coming due pressed their borrowers for payments, who in turn pressed small-scale borrowers among farmers and small tradesmen for payments they could not make—a financial crisis made worse by Massachusetts taxes levied to pay off the state’s war debts. Lincoln’s business was hit as well. Men not as well off, particularly in the western part of Massachusetts, faced foreclosures and imprisonment for debt. That summer farmers—many of them veterans—rioted and forced courts to close at gunpoint.

Lincoln was caught in the same economic vise of falling prices, weakening trade, high taxes and vanishing credit. He nonetheless had no sympathy for the view that their grievances were comparable to those that had fueled resistance to royal government a decade earlier. Massachusetts was no longer ruled by a distant king, a hostile Parliament and a corrupt ministry. It was a republic, governed by elected officials empowered by a state constitution ratified by the people’s representatives. Citizens, he believed, owed the republic their loyalty and obedience to law. The future of the republic, he reflected, was at risk because “there doth not appear to be virtue enough among the people to preserve a perfect republican government.”

The crisis shook his confidence in the idea that a confederation of small republics could endure. Perhaps only a continental republic, possessed of sufficient strength to secure compliance with the law, could survive. As the summer of 1786 turned to fall, Lincoln exchanged letters about the crisis with his old commander. Washington wanted intelligent men to investigate the grievances that had sparked the protest, and redress them if possible. But he would not see rioters destroy the work of the Revolution. “Are we to have the goodly fabric,” he asked Lincoln, “that eight years were spent in raising, pulled over our head?”

A heavy snow in December trapped Lincoln in his house with his thoughts and his pen. The independent states, it seemed—even Massachusetts—could not endure as separate republics. “The injured state of our commerce,” he reflected, as well as “our ruined credit . . . and the contemptible figure we make among the nations of Europe, are the natural consequences and the most conclusive evidences of the want of a federal head.” As the snow piled up, he concluded that the “wellbeing, if not the very being, of the different States depend on a firm union, and a Controuling power at the head of it.”

A thoughtful man, Lincoln had, under the pressure of events, reasoned himself out of republican idealism focused exclusively on the household, town and state, and into a conviction that an effective union of the states with a federal government endowed with sufficient power was essential to preserve the rule of law—law made, not in London, but by the people’s representatives in America. He realized that this involved risks inherent in centralized authority, but the alternative seemed to be anarchy and the end of the republican experiment. Lincoln never abandoned his attachment to the small republic that began at his own fireside, and extended from town to commonwealth. He finally embraced the idea of a continental republic to protect the small republic from degenerating into lawlessness.

Lincoln considered these matters at home that winter, knowing that he would be called upon, as the senior major general of the Massachusetts militia, to lead men into western Massachusetts to maintain order and suppress armed resistance to the law. “A government which has no other basis than the point of a bayonet” was not what they had fought for, he wrote to Washington. It would be “very painful,” Washington acknowledged, for Lincoln to “march against those men whom he had heretofore looked upon as his fellow citizens and some of whom perhaps been his companions in the field.” Yet the alternative, both men knew, was abandoning the rule of law upon which republics must be built.

On January 20, 1787, Lincoln led a volunteer force of three thousand men out of Boston toward the western part of the state to restore the rule of law at the point of a bayonet. That same day, insurgents surrounded Springfield and its federal arsenal. When Lincoln arrived on the scene, he found that Daniel Shays, the leader of the insurgent farmers, had attacked the arsenal but had been beaten back by cannon loaded with grapeshot, leaving four men dead and at least twenty wounded.

Lincoln lost no time in crossing the Connecticut River and forcing the insurgents out of West Springfield. He then turned north and chased Shays and his men to Petersham, close to the northern border of the state. Determined not to give Shays a moment to gather strength, Lincoln led a night march through driving snow and attacked the rebels in Petersham on the morning of February 4. Lincoln captured 150 of the rebels. The rest fled, never to gather in force again.

Lincoln divided his men and occupied towns in Berkshire, Hampshire and Worcester counties where resistance to the law was most troubling. Roving groups of lawless insurgents raided farms and businesses, degenerating into bandits. Lincoln’s scattered troops did their best to stamp out the embers of the rebellion during the spring. The experience was deeply disturbing to Lincoln. “There is a frenzy among these people,” he wrote, “which greatly exceeds what I had any idea to find.”

Lincoln returned to Hingham, never to take up his sword again. He served a term as lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, had the pleasure of representing Hingham at the convention that ratified the Federal Constitution, and served for nearly twenty years as collector of the port of Boston, a lucrative post to which George Washington appointed him in August 1789. Some of his friends suggested the position was not important enough, but they need not have troubled themselves. Although the work required him to spend much of his time in Boston, it rarely took him far from home. Each winter he returned to Hingham and the pleasures of his own fireside.

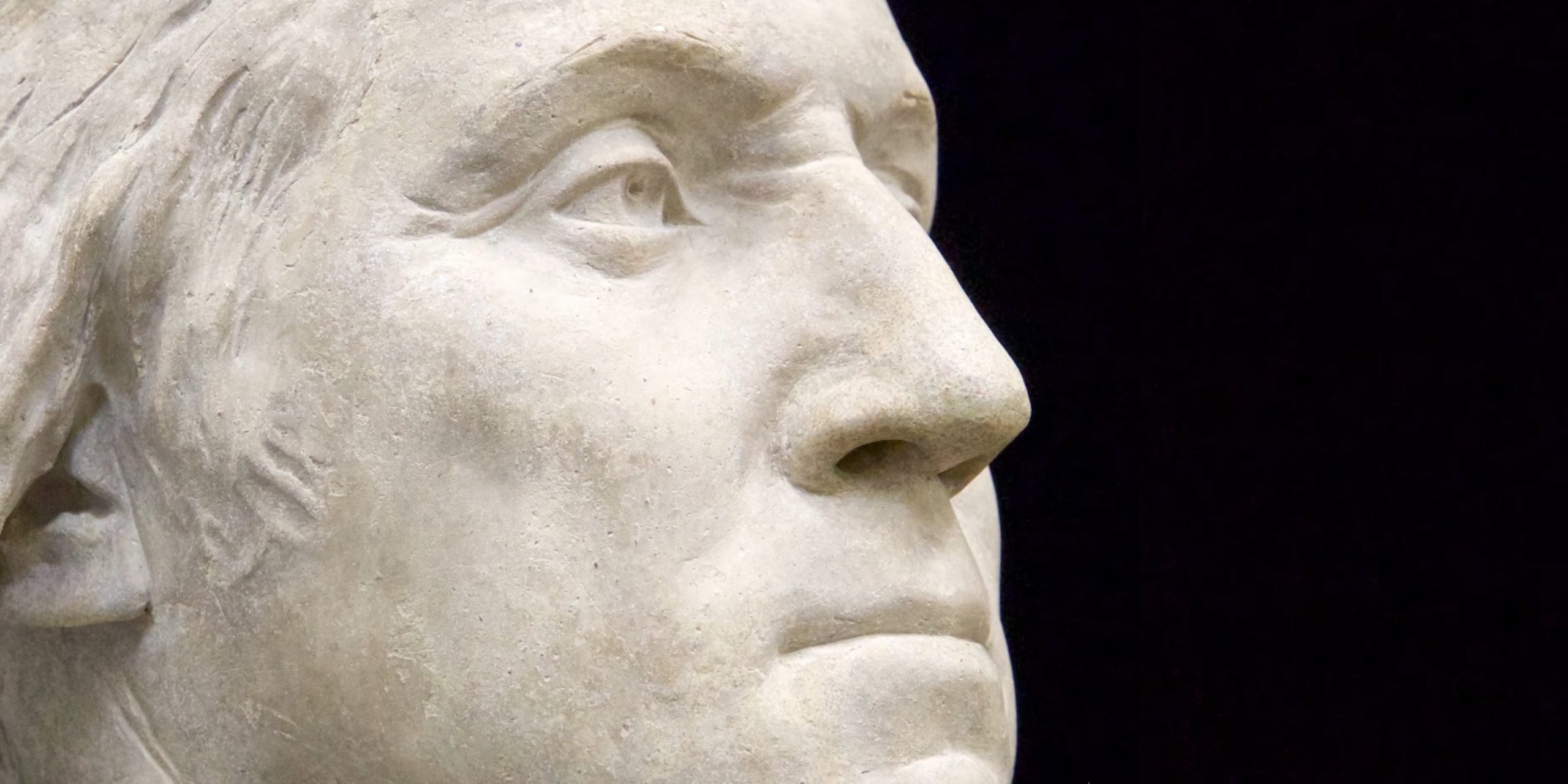

Above: This simple print by John Norman, which appeared in James Murray’s pioneering book, An Impartial History of the War in America between Great Britain and the United States (Boston: Nathaniel Coverly and Robert Hodge, 1782), was the first published portrait of Benjamin Lincoln.