The Revolutionary War was won by thousands of ordinary soldiers. Congress made promises to them—of land grants, bounties, and routine pay—that it was very slow to fulfill, if it fulfilled them at all. Revolutionary War veterans resumed their civilian lives with no help from the free governments they had fought to create. Many struggled. For decades, Congress and the public seemed indifferent to them. That started to change in the years following the War of 1812, as the generation that had fought and won the Revolutionary War began to grow old.

The Legacy of America’s First Veterans asks students to consider the experience of Revolutionary War veterans in the early nineteenth century, how ideas about veterans changed between 1815 and 1835, and how that change reflected and shaped the development of an increasingly democratic culture. The lesson invites students to examine and interpret primary source evidence documenting the lives of ordinary veterans and the public debate about granting pensions to Revolutionary War veterans. That debate concluded with the adoption of the Pension Act of 1832, which created the first wide-reaching military pension program in American history. Like the G.I. Bill of the twentieth century, pensions provided to Revolutionary War veterans shaped the lives of thousands of veterans and expressed the nation’s commitment to the interests of ordinary Americans.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle or High School

Recommended Time

Two +/- fifty-minute sessions

Objectives and Essential Questions

Students will learn:

- how Americans learned to appreciate and honor the contributions and sacrifices of the common soldiers of the Revolutionary War;

- how to use primary source documents to reconstruct the experiences of common solders of the Revolutionary War, using pension records to learn about their service and their post-war lives; and

- how the treatment of Revolutionary War veterans in the 1820s and 1830s reflected and shaped the development of a more democratic society.

Materials and Resources

- Pension File of Chatham Freeman

- Chatham Freeman Worksheet

- Table of Retail Prices, ca. 1835

- A Pensioner of the Revolution by John Neagle, 1830—see also the museum database file on A Pensioner of the Revolution

- Speech of Representative Henry Hubbard, 1832

Background on Revolutionary War Veterans

Over a quarter of a million American men served in the armed forces that won our independence. Between eighty and ninety thousand of them served in the Continental Army, an all volunteer army of citizens. All of these men risked their lives. About seven thousand were killed in battle. At least seventeen thousand soldiers died of disease or in accidents. The total number of soldiers who died from disease may exceed fifty thousand. Records are too fragmentary for us to be sure. As many as twenty-five thousand men were disabled by disease, wounds, or injuries sustained in service.

Those who survived the war became America’s first veterans—the world’s first veterans of an army of free men. The American republic owed its existence to them, but Americans found it difficult to acknowledge that debt, much less honor their service. Cultural traditions inherited from Britain, where common soldiers were held in low regard, shaped the way many post-war Americans thought about veterans. Officers, in their view, might have been motivated by enlightened patriotism, but enlisted men had served for pay. Little else was owed to common soldiers—not even honor.

Following British practice, Congress provided modest pensions for men disabled in service. Some states provided modest benefits to disabled soldiers and a few gave discharged soldiers land grants in lieu of back pay, but most men discharged in good health received nothing. The generals who led them were celebrated as heroes, but ordinary soldiers were rarely honored in the first decades after the war’s end.

Their fellow citizens came slowly to the realization that the common soldiers of the Revolutionary War were heroes, too. Those who lived to be old men were finally recognized as honored veterans of a revolution that had created the first great republic of modern times. Prompted by President James Monroe, a veteran of the Continental Army, Congress adopted the Pension Act of 1818, calling for pensions for Continental Army and Navy veterans in financial need.

This was a first step, but in spirit and practice it was much more like poor relief—or what we call today welfare payments—than a modern military pension. Today we think of military pensions as a reflection of our gratitude for those who serve in our defense and as a benefit veterans have earned. This way of thinking about military pensions and the veterans who qualify for them was shaped by the national discussion about providing for Revolutionary War veterans that took place between 1818 and 1832. In 1832 Congress decided to award pensions to the surviving veterans of the Revolutionary War. These were the first pensions paid to American veterans without regard to rank, financial distress, or physical disability. They reflected the gratitude of a free people for the soldiers who secured their freedom.

Sequence and Procedure

We recommend engaging students with three very different but related exercises involving three different kinds of primary sources—a series of documents relating to a single veteran, a contemporary portrait of a homeless veteran, and a speech in favor of pensions for nearly all surviving Revolutionary War veterans, delivered in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1832. These sources span the years from 1818, when Congress passed a law providing pensions to impoverished Revolutionary War veterans, to 1832, when Congress adopted a new pension law that provided financial support to nearly all surviving Revolutionary War veterans, regardless of financial need.

Teachers should feel free to adapt these exercises or use one or two but not all three, as their goals and circumstances dictate. The strategy suggested here is to present the background and the first two exercises in class, and assign the third exercise as an assessment to be completed as homework. All three exercises can be readily adapted for asynchronous learning.

Part One: Reconstructing the Life of Chatham Freeman, an African American Revolutionary War Veteran

This exercise challenges students to extract facts from a set of five short primary source documents to reconstruct the Revolutionary War service and later life of a Revolutionary War veteran. This exercise reinforces the background information on the Pension Act of 1818 by using the case of an actual Revolutionary War veteran’s application for a pension under the law. It also brings students face-to-face with reconstructing the life of an ordinary American from primary sources. The exercise has the added benefit of encouraging students to understand and appreciate the role of African American soldiers in the Revolutionary War, because the pension file under examination is the file of an African American named Chatham Freeman, one of thousands of African Americans who served in the armed forces that won American independence. We chose his file because of this fact, though in most respects his file is similar to that of thousands of white veterans who were successful in securing a pension under the 1818 law. Chatham Freeman’s file has the additional benefit of being relatively easy to read in its original manuscript form (they are reproduced in the image gallery below), if you choose to ask students to try. If not, they can use the transcripts supplied with the Materials and Resources. The questions suggested below are provided in worksheet form supplied with the Materials and Resources.

Like thousands of other Revolutionary War veterans’ pension files, the pension file of Chatham Freeman is now in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The file documents his application for a pension under the Pension Act of 1818. This selection consists of five one-page documents. You should guide the students through an overview of the purpose of each document before starting the exercise.

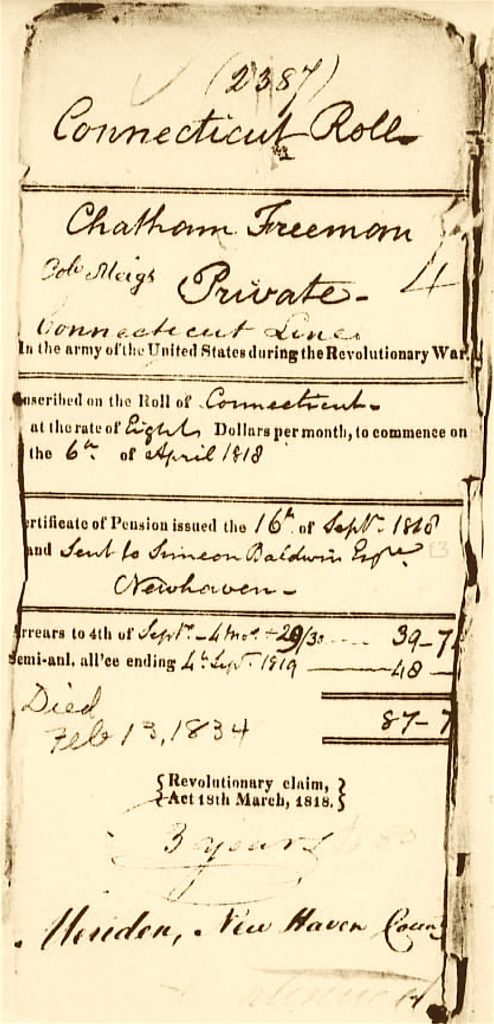

COVER: The first document is the cover, which is a partially printed form filled in with his name and other information. The cover was folded with the contents of the file inside. Early pension files like this one were tied with a thin piece of red ribbon to keep the pages all together. This ribbon, which was referred to as tape in the nineteenth century, is the source of the phrase “red tape,” used to refer to bureaucratic requirements. The pension system was the first federal bureaucracy that touched the lives of many thousands of ordinary civilians, who were usually anxious to “get through the red tape,” which means get through all the government requirements to secure a pension.

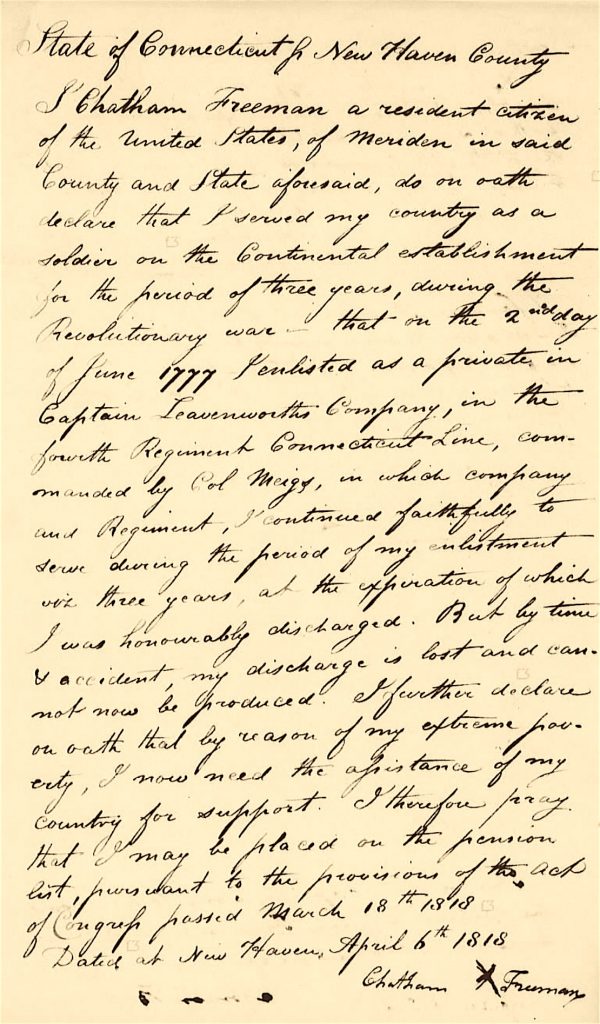

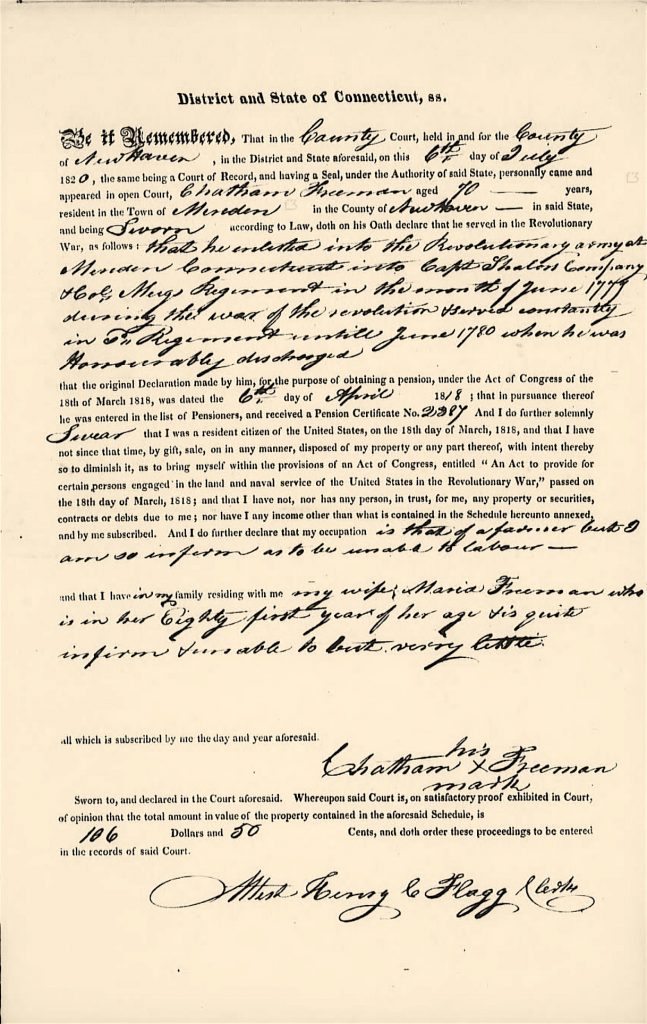

PENSION DECLARATION: The second document is the pension declaration. The Pension Act of 1818 required that Revolutionary War veterans applying for pensions go to a local court and provide a statement to a judge swearing to a set of facts about their military service in the Revolutionary War, including the dates of their enlistment, the units in which they served, the names of their commanding officer, and the dates of their discharge. The law required each veteran to produce his written discharge from service if he had it, but most Revolutionary War veterans, including Chatham Freeman, had long since lost their discharge papers. The pension declaration was usually written up by a court clerk or an attorney from a statement given orally by the veteran, but some pension declarations were written by the veteran himself. In either case, the veteran had to sign the pension declaration, swearing to the truth of what he reported. If a veteran was unable to sign his name, he wrote an X on the document and someone wrote his name on either side of the X, sometimes adding the words “his mark” to indicate that the veteran had made an X in place of a signature.

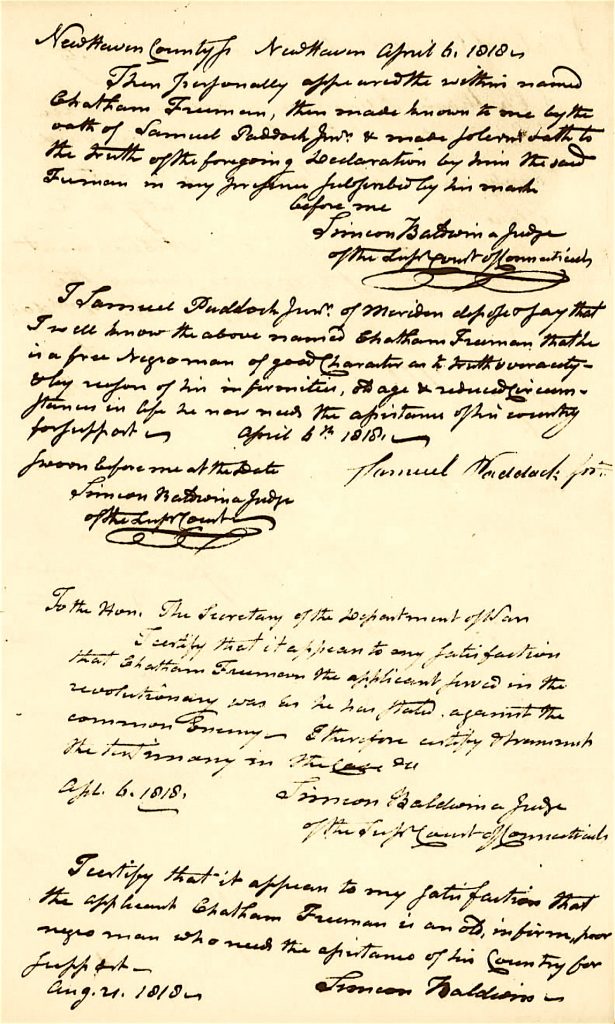

AFFIDAVITS: The third document is perhaps the most complicated to understand, but it is important and contains useful information. This is the affidavits. These always include a short statement written and signed by the judge who heard the pension declaration, affirming that that he had heard the statement of the applicant. The affidavits also usually include the signed statement of someone who knew the applicant, attesting to the applicant’s truthfulness and financial need, and additional statements by the judge, one indicating that the applicant believes that the applicant served in the Revolutionary War as he described, and another that the veteran is in financial need and so qualified for a pension under the law. Sometimes the last two were combined with the initial statement of the judge that the applicant had appeared before him to make his declaration.

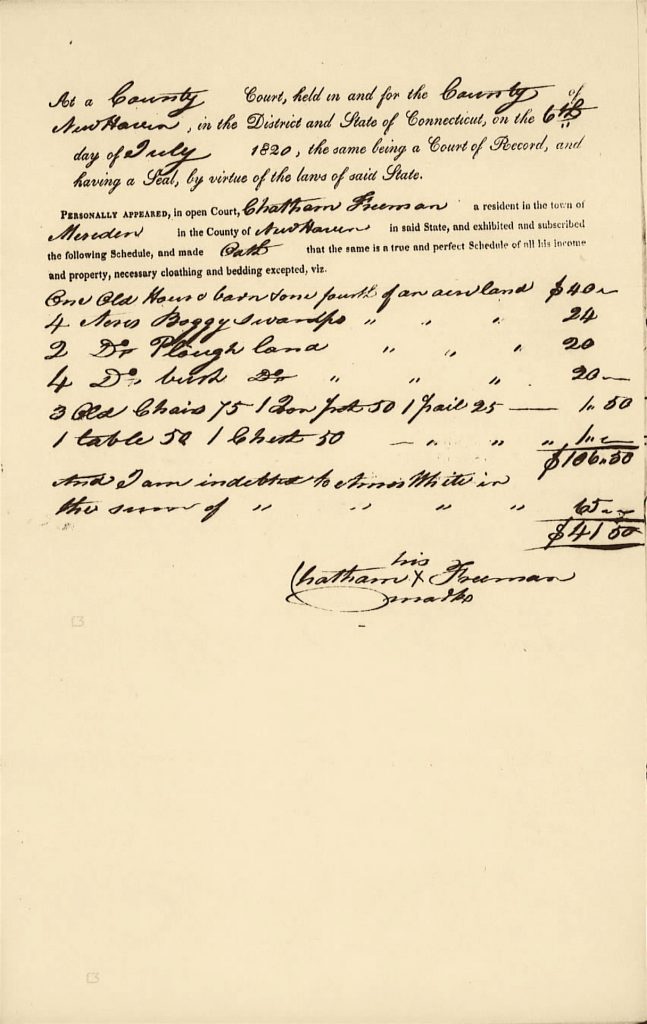

PROPERTY INVENTORY: The fourth document is a list of the veteran’s property along with an estimate of the value of each item, added up to give the value of everything on the list. This property inventory, or property “schedule” as it was called, is recorded on a partially printed form filled out by a court clerk. The applicant signed it or “made his mark” in place of his signature. For pensions awarded under the Pension Act of 1818, these property inventories are dated 1820 or later. What had happened is that in 1818, 1819, and 1820, many more Revolutionary War veterans were awarded pensions than Congress had predicted. An additional, or supplemental, law was passed in 1820 requiring every pensioner, and every new applicant, to appear in court and provide an inventory or “schedule” (in this case, “schedule” simply means a list and has nothing to do with time) of his property. The purpose of this document was to prove financial need. The federal officials in charge of pensions reviewed these inventories and decided whether the pensioner or new applicant was truly poor. If the reviewer decided a pensioner was not poor, he would be “dropped from the rolls,” that is, taken off the pension list and no longer sent a pension. These property inventories are very useful documents for understanding how people lived at the time, since they were required to list everything they had of any financial value except for their clothes, beds, sheets, and blankets. These inventories tell us about the applicant’s house and land (if he owned either), and usually includes his furniture, cooking equipment, tools, and any horses, cattle, pigs, or other livestock he owned. These documents help us picture how Revolutionary War veterans and others of their age or neighborhood lived.

SWORN STATEMENT: The fifth document is a sworn statement required of all Revolutionary War veterans awarded pensions between 1818 and 1820, repeating the basic facts presented in their original pension declarations, documenting the number of their pension certificate (all pensioners were given a pension certificate with a unique number, something like a modern social security number), and swearing that they had not given away their property since being awarded a pension, in order to appear poor. The pensioner was required to state his occupation, name anyone who lived with him, and sign or “make his mark.” A court official signed the document as well, indicating the total value of the property in the attached property inventory. This document was sent to the federal government which used it, long with the property inventory, to determine whether a veteran who had been given a pension between 1818 and 1820 would continue to receive it.

Now that the class is acquainted with the purpose of each of the five documents in Chatham Freeman’s file, we can pose questions about his life and circumstances that the students can answer by using these five documents.

These five documents do not tell us much about Chatham Freeman before he joined the Continental Army, but we know a little bit from other sources that the teacher can share with the class. We do not know where Chatham Freeman was born, but it is possible that he was born in Africa and brought to America by slave traders when he was a child or a young man. When the Revolutionary War began in 1775, he was a slave to Noah Yale (1723-1803) of Wallingford, Connecticut. He was probably known simply as “Chatham” before the war, with no last name, although if he was born in Africa he undoubtedly had a name in his African language. The name “Chatham” probably refers to William Pitt, earl of Chatham, the most important leader in the British Parliament during the French and Indian War. William Pitt was given the title earl of Chatham in 1766, so we can imagine our “Chatham” was given that name then or sometime shortly after. We do not have any direct evidence of the work he did, but we can guess he was a farm laborer.

Noah Yale was a farmer. He and his wife, Anna, had ten children between 1745 and 1768—seven boys and three girls. Three of the boys and one of the girls died before the Revolutionary War, leaving the Noah and Anna with four sons and two daughters. The eldest surviving son, named Noah after his father, died in December 1776, while serving as soldier. He was twenty-seven when he died. His three surviving brothers were Thomas (age twenty), Joel (age seventeen) and Asahel (age twelve). Thomas served in the Connecticut militia from August to December 1776, returning home when his elder brother died.

When the militia was called out in the spring of 1777, Noah Yale offered Chatham as a substitute for one of his sons—either Thomas or Joel—to spare the son from militia service. Under Connecticut law, young white men were required to serve in the militia, but enslaved men like Chatham were not required. Their enslavers could offer them as substitutes. We can imagine—this is an interpretive judgment about something we do not know for sure—that the death of the younger Noah Yale in December 1776 shook the family and made Noah and Anna reluctant to have Thomas return to military service or to have Joel serve at all.

No portrait of Chatham Freeman survives, and none was probably ever made. This preliminary figure for the proposed—and long overdue—Black Revolutionary War Patriots Memorial in Washington, D.C., was sculpted by Ed Dwight in 1992 and is in the museum collections of the American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati. The memorial would honor Chatham Freeman and the thousands of other African American soldiers and sailors who served in our struggle for independence.

Chatham enlisted in the Continental Army based on a promise from Noah Yale that he would be freed at the end of his service. We know this because at the end of the war Noah Yale went before the local court and officially released Chatham from slavery. A record of that action survives. No mention of this background appears in Chatham Freeman’s pension file, and there is no reason it should, since in 1818 he had been a free man for decades. Like many free African Americans, he used the last name “Freeman,” probably from the time he was released from enslavement. It might have been given to him by the court, or he might have chosen this last name himself. We do not know for sure. Freeman was a common name among free African Americans in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century and it remains a common name among African Americans today.

Using the five pension documents as primary source evidence, answer the following questions to reconstruct the life of Chatham Freeman:

- In what year was Chatham Freeman born? This is a good question to start with, because finding the answer isn’t simple and the student will wind up going over all the documents to find the answer. At the beginning of the sworn statement (Document 5), Freeman says he is seventy years old. This document is dated 1820, which means that he was born about 1750.

- In what year did Chatham Freeman enlist in the Continental Army? In his pension declaration (Document 2), Freeman says he enlisted on June 2, 1777. In his sworn statement (Document 5), he says June 1777.

- What regiment did Chatham Freeman serve in? In his pension declaration (Document 2) he says he served in the “fourth Regiment, Connecticut Line,” commanded by Colonel Meigs. In his later sworn statement (Document 5), he says he served “Col. Meigs Regiment.” This is actually a good example of how people can misremember fairly important facts. Col. Return Jonathan Meigs (yes, Return is an unusual first name) was the colonel of the Sixth Regiment of the Connecticut Continental Line. Students can confirm this by doing a simple Google search for “Colonel Meigs Connecticut Revolutionary War.” Remind the class that Chatham Freeman was sixty-eight years old in 1818, and he had enlisted forty-one years before. People forget things.

- How long did Chatham Freeman serve in the Continental Army? When was he discharged? In his pension declaration (Document 2) he says he served three years. In his sworn statement (Document 5) he says he was honorably discharged in June 1780.

- What was the name of Chatham Freeman’s wife? When was she born? In his sworn statement (Document 5), which was made in 1820, he identifies his wife (near the end of the document) as Maria Freeman, and says she is “in her Eighty first year,” which is a way of saying she was over eighty but not yet eighty-one. If she was eighty in July 1820, she was born about 1740. She was about ten years older than her husband.

- Could Chatham Freeman read and write? How do we know? He couldn’t write his name, so he probably couldn’t read or write. He “made his mark” on his pension declaration (Document 2), his property inventory (Document 4) and his sworn statement (Document 5), signing his name with an X.

- Is there anything in Chatham Freeman’s pension file that indicates he was an African American? If so, what? This information is only found in the affidavits (Document 3), where it appears in two places. The second affidavit, signed by a man named Samuel Paddock, Jr., says that “I well know the above named Chatham Freeman that he is a free Negro man of good character.” This statement is dated April 6, 1818. At the bottom of the same document, Judge Simeon Baldwin wrote on August 21, 1818: “I certify that it appears to my satisfaction that the applicant Chatham Freeman is an old, infirm, poor negro man who needs the assistance of his Country for support.”

- In 1820, Chatham Freeman was required to list all his property to prove that he was poor. Did he own his own house? In his property inventory (Document 4), Chatham Freeman reported that he owned “One Old House & barn” sitting on one-fourth of an acre of land.

- What other land did he own and what was it like? In his property inventory (Document 4) he says he owned four acres of “Boggy Swamps,” two acres of “Plough land,” and four acres of “bush land.” In other words, he owned ten acres plus his house lot. Only two of the ten acres was suitable for farming—the “Plough” or plow land. The rest was “bush,” which means land covered with bushes and small trees, and swamp, which might be made into farmland if it were property drained. Two acres of farmland was plenty to grow fruits and vegetables to sustain two people.

- What was Chatham Freeman’s house like? How was it furnished? The property inventory (Document 4) says that he didn’t have to list his bedding, so we can assume he had a bed and didn’t list it. The only furniture listed is three old chairs worth seventy-five cents, a table worth fifty cents, and a chest worth fifty cents. It seems from this description that it might have been a one- or two-room house, consisting of a sleeping room or space and a place for table and chairs where the couple ate. The rest of their property consisted of one iron pot worth fifty cents and one pail, or bucket, worth twenty-five cents.

- What was all of Chatham Freeman’s property worth in 1820? Did he have any debts? The property inventory (Document 4) gives the total value of his house, land, and furnishings as $106.50. He reported that he owed a man named Amos White $65, meaning that what we now call the total net worth of his property, with debts subtracted, was $41.50 (we know from other sources that the man who had loaned him money, Amos White, was the local silversmith and was born in 1746, so he was a little older than Chatham Freeman). The sworn statement (Document 5) gives the $106.50 figure as the value of all of Chatham Freeman’s property.

- When he worked, what kind of work did Chatham Freeman do? Was he or his wife able to work in 1820? How do we know? According to the sworn statement (Document 5), Chatham Freeman said his occupation “is that of a labourer but I am so infirm as to be unable to labour.” He reported that his wife was “quite infirm & able to do but very little.” An attentive student might notice that on the property inventory (Document 4), Freeman did not include a plow, shovel, hoe, or any other farming tools, nor anything else to suggest that Freeman or his wife were doing any kind of work. They were both too old to do much manual labor.

- Chatham Freeman was able to prove he was poor and so received a pension under the Pension Act of 1818. How much did he receive? The cover (Document 1) says that Freeman received a pension of eight dollars a month, or ninety-six dollars a year. Thus his yearly pension was worth twice as much as the net worth of his property.

- Using the Table of Retail Prices provided, consider what Chatham Freeman and his wife, Maria, could buy with eight dollars a month. Considering the fact that they owned their house and the land they lived on and did not have to pay rent, was eight dollars a month enough to live on? Explain your answer, describing how they might have spent the money.

- When did Chatham Freeman die? The cover (Document 1) says that he died on February 13, 1834. He was about eighty-four years old.

Part Two: Examining the First Portrait of a Homeless Veteran

During the 1820s, the federal pension office dropped thousands of veterans from the pension list because they failed to appear in court to provide an inventory of their property or the property inventories they provided suggested to the pension office that they were not poor enough to qualify for a pension under the act of 1818. This effort to cut costs disappointed the veterans who lost their pensions, and it brought widespread public attention ro the fact that pension law only applied to Revolutionary War veterans who had served in the Continental Army. Most Revolutionary War veterans had served in state regiments or in the militia. By the late 1820s, as most of the surviving Revolutionary War veterans were past seventy years old and few of them were able to work any longer, their distress became a subject of public debate. Did the people, acting through the federal government, owe all surviving Revolutionary War veterans a pension to help support them in their old age?

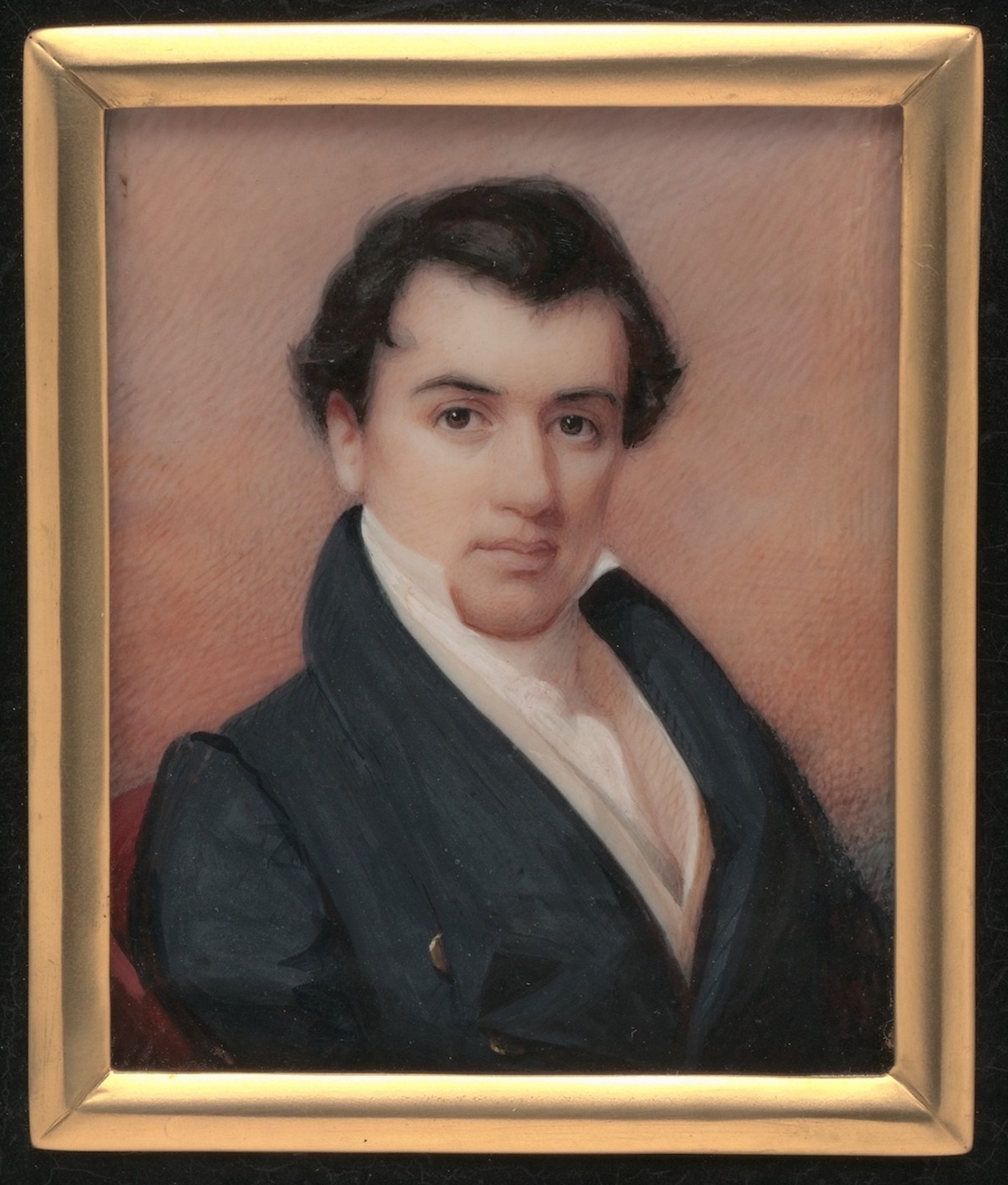

Daniel Dickinson painted this portrait miniature of fellow artist John Neagle in 1830, the same year Neagle (who was then thirty-three) painted his portrait of homeless Revolutionary War veteran Joseph Winter (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

This question became a political issue in the presidential election of 1828, in which Andrew Jackson, who had served with the militia as a boy during the Revolutionary War, defeated John Quincy Adams. Jackson supported extending pensions to many more Revolutionary War veterans, but Congress took no action on the idea in 1829, the first year of Jackson’s presidency. The issue remained a subject of public discussion.

On a snowy night in December 1829, a successful young Philadelphia painter named John Neagle was walking to visit a friend when he noticed an elderly man huddling under a makeshift shelter. His clothes were ragged and the man was having trouble keeping warm. Neagle spoke to him, and then invited the man back to his home, where he gave him something to eat and a chair beside the fireplace.

The man told Neagle that his name was Joseph Winter, and that he had served in the Revolutionary War. After the war he had worked as a weaver, but he was too old to work and his wife and children were all dead. He had no one to help care for him in his old age.

Neagle painted a portrait of the old veteran, who stayed with the artist for several days before setting off to find friends in another town. In 1831 an engraver made a print of the portrait, which was sold to the public under the title Patriotism and Age.

Ask the class to examine the portrait, which is the oldest known portrait of a homeless American veteran. Unlike many portraits painted in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Neagle made no effort to portray Joseph Winter as a handsome gentlemen. In a class discussion, ask the students to describe their reaction to the painting. Most of these are subjective questions, which is inevitable, because the painting was clearly intended to appeal to the emotions of its viewers.

John Neagle’s portrait of Joseph Winter later became known by the title A Pensioner of the Revolution, though there is no evidence Winter ever received a pension for his service. His haunting portrait came to symbolize the elderly Revolutionary War veterans finally recognized by the passage of the Pension Act of 1832 (American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati).

- What words would you use to describe Joseph Winter’s appearance? Students may suggest old, tired, sick, sad, ragged, sorrow, worn-out, and ideas of a similar sort.

- Do you think John Neagle intended people who saw the painting to react in the same way? Why? Neagle seems to have been moved by his encounter with Joseph Winter, and the portrait seems to have been intended to produce similar emotions in his audience.

- Why do you think John Neagle painted this portrait? Was he motivated by profit or something else? If so, what? Although Neagle probably shared in the profits from the sale of the engraving and ultimately sold the painting, he surely didn’t paint it to make money. He was in demand as a portrait painter and could earn money painting portraits of wealthy men and their families. He probably painted Joseph Winter to startle people into supporting the push to provide pensions to more Revolutionary War veterans.

- When people saw the engraving of the portrait for sale, with the title Patriotism and Age, do you think they recognized that it was a portrait of a Revolutionary War veteran? Why or why not? People probably did recognize the subject as a Revolutionary War veteran, because by 1831, when the engraving was sold, pensions for Revolutionary War veterans had become a major political issue.

- Why would someone have bought an engraving of an elderly man they didn’t know? Many people collected engravings, which was one of the few ways people could enjoy fine art before art museums and generously illustrated art books became common. This engraving would have appealed to people who felt strongly about the pension issue and people whose fathers or grandfathers were Revolutionary War veterans.

- Do you think Joseph Winter received a pension under the Pension Act of 1818? Why or why not? If Winter had been receiving a pension under the 1818 law, he probably wouldn’t have been homeless. While we don’t know for sure, he was probably a veteran of the militia or the Pennsylvania Associators—private, voluntary military units formed during the Revolutionary War. Such veterans were not eligible for pensions under the act of 1818. Also, if Winter had received a pension under the act of 1818, he would have a pension file in the National Archives like Chatham Freeman. He does not.

Assessment and Demonstration of Student Learning

On December 28, 1831, Representative Henry Hubbard of New Hampshire introduced a bill in the House of Representatives to extend pensions to all surviving Revolutionary War veterans who had served for at least six months, regardless of whether they served in the Continental Army or Navy, with state regiments, or in the militia. The bill called for each enlisted man who had served for nine months or more to receive ninety-six dollars a year, and those who served six to nine months to receive sixty-four dollars a year. The bill also called for ending the condition imposed by the Pension Act of 1818 that veterans prove their poverty to qualify for a pension. Under the proposed law, financial need was no longer a consideration.

Henry Hubbard, portrayed here by Chester Harding in about 1846, served New Hampshire as congressman, senator, and governor. Leading the fight for the Pension Act of 1832 was a high point of his career (New Hampshire Historical Society).

Opponents worried that such a pension system would be too costly. Others thought that the federal government would end up paying pensions to men who were perfectly able to take care of themselves, and those who had been enrolled in their local militia during the Revolutionary War but never marched away from home or risked their lives in the common cause. The highlight of debate was Hubbard’s speech introducing the measure. After debate, the bill passed the House of Representatives 126-48 and the Senate 24-19. President Jackson signed the bill into law on June 7, 1832.

Ask students to read the selections from Hubbard’s speech included with the Materials and Resources, and then write a brief paper, summarizing Hubbard’s arguments on the following points:

- Revolutionary War veterans of state regiments and militia are just as deserving of our gratitude as Continental Army;

- Revolutionary War veterans should not be required to show financial need to qualify for a pension; and

- Providing pensions to Revolutionary War veterans is not an act of charity. It is, in fact, the payment of a just debt.

After summarizing Hubbard’s arguments, explain in brief how the Pension Act of 1832 reflected changing attitudes toward ordinary people and the the increasingly democratic character of American life in the 1820s and 1830s.

Revolutionary Achievements Category

National Identity, Our Highest Ideals

Exploring the Revolutions Category

The Legacy of the Revolution

Read More about Revolutionary War Veterans

Read about other African American Revolutionary War veterans in The Elusive Peter Hunter and The Heroic Jeffrey Brace. These essays make excellent class reading assignments, especially in connection with this lesson’s work on the pension application of Chatham Freeman.

Read more about homeless veteran Joseph Winter in Joseph Winter, Lone Wanderer.

This lesson is based on our exhibition America’s First Veterans, and on the book America’s First Veterans, published by the American Revolution Institute in November 2020.