Artillery in the eighteenth-century was high-tech business. Using the original six-pounder cannon on display in Anderson House as a focus for interpretation, the American Revolution Institute is creating a hands-on, educational experiences for visitors highlighting the role of teamwork and skill that made the Continental Artillery a powerful contributor to victory in the Revolutionary War. A collaborative effort between Executive Director Jack Warren, History and Education Associate Evan Phifer and South Carolina Society member William Marshall, the Institute is creating highly accurate reproduction artillery tools and ammunition to show visitors, especially school children, at Anderson House how cannon teams operated and how cooperation and coordination were key components to the success of the Continental Army.

Below are highlights of the project so far.

Now affectionately known as “George,” this six-pounder field piece is one of the few American-made bronze cannons to survive from the Revolutionary War. The barrel was cast for the Continental Army in 1777 at the Philadelphia foundry of James Byers. After the war, most cannon barrels were melted down for other uses. This one survived because it was used as a gatepost in an ornamental fence surrounding the monument in Charleston, South Carolina, to Revolutionary War hero William Washington. The top of the barrel is marked with the letters US surrounded by a ribbon that bears a mostly obliterated Latin inscription. Piercing the US emblem is a vindicta—a rod of freedom—with a liberty cap on top of it. Removed from the fence and conserved by the South Carolina Society of the Cincinnati, the cannon is now on long-term display at the American Revolution Institute. Its mate, known as “Martha,” is on long-term display at the Charleston Museum.

Now affectionately known as “George,” this six-pounder field piece is one of the few American-made bronze cannons to survive from the Revolutionary War. The barrel was cast for the Continental Army in 1777 at the Philadelphia foundry of James Byers. After the war, most cannon barrels were melted down for other uses. This one survived because it was used as a gatepost in an ornamental fence surrounding the monument in Charleston, South Carolina, to Revolutionary War hero William Washington. The top of the barrel is marked with the letters US surrounded by a ribbon that bears a mostly obliterated Latin inscription. Piercing the US emblem is a vindicta—a rod of freedom—with a liberty cap on top of it. Removed from the fence and conserved by the South Carolina Society of the Cincinnati, the cannon is now on long-term display at the American Revolution Institute. Its mate, known as “Martha,” is on long-term display at the Charleston Museum.

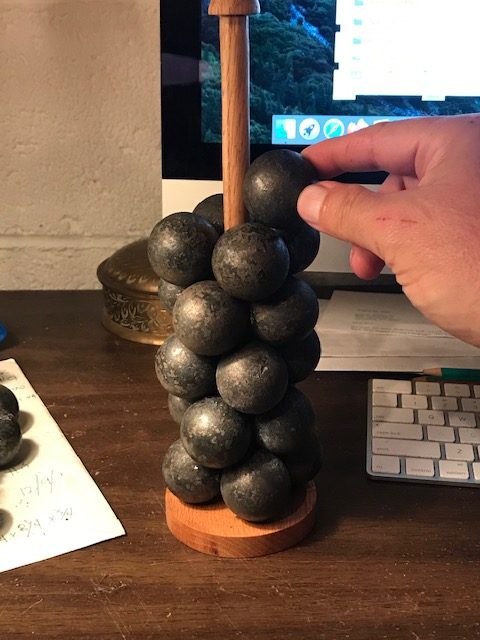

A round of grapeshot consisted of a cluster of iron balls packed around a wooden rod fixed to a round wooden base (a tompion) and covered with cloth stitched to hold the balls together in a tight bundle like a cluster of grapes. Tompion and cloth disintegrated when a round of grapeshot was fired, and the balls blew out of the cannon like a shotgun blast. This ca. 1799 illustration, as well as John Muller’s 1757 Treatise of Artillery, served as a guide while recreating an authentic round of grapeshot.

The tompion had to be made to fit inside the mouth of the barrel. A standard six-pounder cannon bore had a diameter of 3.67 inches. Equipment and ammunition such as the sponge head, rammer, cannon ball and grapeshot needed to fit within the bore of the cannon. Institute staff decided to make our tools and grapeshot tompion base, as shown in photo, roughly half an inch less than the standard bore diameter.

Iron balls were stacked on top of each other and quilted in cloth to create grapeshot. Critical to understanding the process of creating this shot was Muller’s Treatise of Artillery which explained that “the number of shot in a grape varies according to the service or size of the guns . . . it must be observed, that whatever number of sizes of the shots are used, they must weigh with their bottoms and pins, nearly as much as the shot of the piece.” Here, Executive Director Jack Warren uses Muller’s instructions to determine how many iron balls are needed to produce a six-pound grapeshot.

The idea for the project started several years ago when “George” was placed in Anderson House with the assistance of William Marshall. While setting up the cannon, Executive Director Jack Warren mentioned he wanted someone to make a set of tools to show how the piece would be fired and the teamwork needed to do it. In the meantime, Marshall was busy carving spoons, spatulas and other items for a friend and thought Warren’s idea would be an appropriate project as the nation battled COVID-19. Marshall says the numerous details and intricacies of each tool make the project a fun challenge, “truly the Art of the War.”

The construction of the sponge, rammers and worm was based on eighteenth-century illustrations and surviving examples. While firing a cannon, artillerymen used a damp sponge to extinguish any smoking remnants from previous firing, the corkscrew-like worm removed surviving pieces of the cartridge or round from the barrel and the rammer was used to push the powder and shot down the barrel. The linstock at the bottom holds a lighted match used to fire the artillery piece.

William Marshall is also working on a box and rack that will hold our reproduction items for display at Anderson House alongside the cannon, reinforcing to visitors the many pieces of equipment needed to load and fire eighteenth-century artillery.

William Marshall is also working on a box and rack that will hold our reproduction items for display at Anderson House alongside the cannon, reinforcing to visitors the many pieces of equipment needed to load and fire eighteenth-century artillery.

To learn more about Revolutionary War artillery, visit Boom! Artillery in the American Revolution.