Prints created during the Revolutionary War by American, British, French and other Continental printmakers offer unique insights on how contemporaries—artists, engravers and their audiences—viewed the people, events and ideas of the American Revolution. The ten Revolutionary War prints featured here—including portraits, battle scenes, political cartoons and allegorical images—represent genres that attracted printmakers and their audiences. They also represent the variety of methods employed by printmakers, from simple copperplate engravings to mezzotints, etchings and composite prints involving more than one printmaking technique. Illustrated prints served as one of the most accessible forms of mass communication and conveyed a visual language for political messages with clarity and emotional resonance.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, prints had become an important medium for disseminating information about news and events. European artists had also raised printmaking to new heights of technical sophistication. As either illustrations in books and pamphlets or as separately published works, prints were collected by a growing number of consumers for whom fine prints were a sign of refined taste and engagement with public affairs. Specialty print shops in European cities served this consumer market and exhibited new prints in elaborate displays designed to attract connoisseurs and casual buyers. American printmaking lagged far behind European printmaking during the eighteenth century, but the American Revolution created a market for printed portraits of American leaders and depictions of events in America. These images often carried propagandistic tones and were sometimes hastily produced, yet they provided a sense of immediacy and conveyed how contemporaries viewed the unfolding events.

A British satire on the OUTBREAK OF CONFLICT

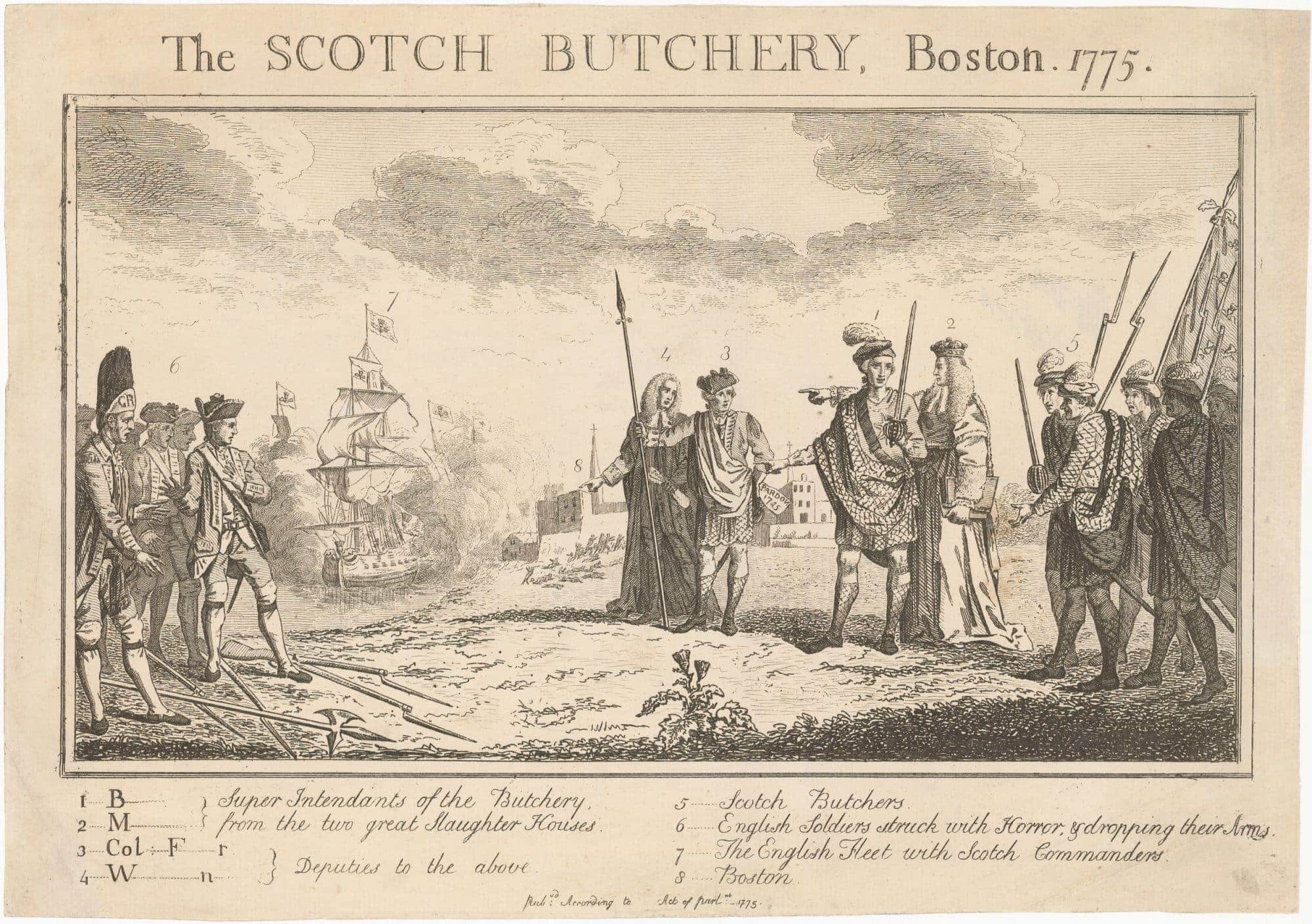

The Scotch Butchery, Boston, 1775.

London: Published According to Act of Parliament, 1775

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Political cartoons played a key role in reporting and shaping public opinion about the American Revolution. These cartoons were often illustrated visual satire and used symbolic images to inspire pointed response. For example, the Battle of Lexington was turned into a subject of ridicule or criticism, with cartoons that mocked British military leadership or displayed colonists as either rebellious children or brave defenders of liberty, depending on the artist’s view.

The Scotch Butchery was a political cartoon that accused a secret faction of perpetrating an offense against citizens of Boston. The cartoon illustrated the Scottish lords Bute and Mansfield directing the attack by an “English fleet with Scotch commanders” who appear to goad on a force of Highlanders toward the city of Boston. Though the unit did not see action in Boston, the soldiers were likely a reference to the Seventy-First Regiment of Foot, also known as “Fraser’s Highlanders,” raised in 1775 for service in the American colonies. Fellow Scots Colonel Fraser and Solicitor General Wedderburn receptively gaze upon the scene, while at the left are “English Soldiers struck with Horror, & dropping their Arms” at the sight of the Highlanders. The precise date of this print is unknown, which presents an interesting puzzle in determining how news of tensions in Massachusetts Bay Colony was reported in London. The small silhouettes of fugitives in Boston appear unarmed and may represent harmless individuals caught up in the emerging conflict. Yet, if the cartoon intended to depict an actual scene of the Revolution, it may be either the April 19, 1775, retreat of British troops to Boston after Lexington, or the bombardment of Charlestown during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. The illustrator of the print may have combined accounts of the news along with public sympathies to present an allegory of the increasingly harsh measures imposed by Parliament in the wake of the Boston Tea Party of December 1773.

RepresEntation of the great Fire of New York

Attributed to André Basset, artist, and Francois Xav. Habermann, engraver

Representation du Feu Terrible a Nouvelle Yorck

Paris: Chez Basset Rue S. Jacques au coin de a rue des Mathurins, 1777

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

The Great Fire of New York was a destructive blaze that burned through the night of September 20, 1776, and destroyed a fifth of the buildings in New York City. The fire resulted in food and housing shortages for a population torn between loyalists, patriots and more moderate citizens. The cause of the fire was contested as British leaders such as Sir William Howe believed it arson, while city residents accused either British forces or their revolutionary adversaries for the inferno. Though the origin of the fire has never been determined, the explanation in this French etching blamed Americans for the conflagration. The fire resulted in military occupation of New York City under martial law, and power was not returned to civilian authorities until evacuation of the British in November 1783.

Prints and engravings such as this French etching, Representation du Feu Terrible a Nouvelle Yorck by André Basset, served as international news of shocking events as they unfolded in the American colonies. The image depicts New York burning while people evacuate and loot buildings, and red-coated soldiers accost citizenry. The description mentions locations such as King’s College (Columbia University), the Bourse (Exchange) and the Lutheran Chapel, however the depictions were imagined by the engraver. These fictitious prints presented news as imagined by European viewers. This brightly colored print was also intended to be projected onto a screen using a “magic lantern” device called a zograscope that employed candles, mirrors and a magnifying lens. Known as vue d’optiques, their popularity in European cities demonstrated the demand for artistic constructions and a desire for viewership of the unfolding events in North America.

An early view of the Battle of Bunker Hill

Robert Aitken, artist and engraver

A Correct View of The Late Battle at Charlestown June 17th. 1775

Philadelphia, 1775

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Engraving by Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken after an earlier image of the Battle of Bunker Hill created by Bernard Romans. Romans was a surveyor and cartographer who was outside Boston when the battle took place, Aitken was an early American publisher and printer in Philadelphia. Romans initially drew a sketch of the battle based on his knowledge of the setting and descriptions of participants. He traveled to Philadelphia that summer and placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette on September 20, 1775: “It is proposed to print an exact view of the late Battle at Charlestown, June 17, 1775 . . . on good crown imperial paper, to be delivered to the subscribers in about ten days: The price to the subscribers is 5s. plain, and if colored 7s.” Before the print was ready to sell, Aitken obtained one of the prints, copied it—without any credit to Romans—and offered it for sale. Aitken’s version was published as the frontispiece of the September 1775 issue of the Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Monthly Museum. In an advertisement published in the Pennsylvania Ledger on October 7, the frustrated Romans described his view as “much superior to any pirated copy now offered or offering to the public.” But it was too late. Aitken’s cheaper pirated version had saturated the market.

The depiction of the battle scene is simplistic with some important details often included as references in the top margin. British warships fire in support of British troops who were commanded by Admiral Sir Richard Howe. Charlestown, at right center, is in flames, as it was after Howe ordered his warships to fire heated shot into the town. The British army advanced in lines, as it did during a series of assaults during the battle. This tactic of advance was adopted to overcome the Continental Army, then under command of General Artemas Ward and General Israel Putnam. On the third assault, the British resorted to a more conventional tactic of advancing rapidly in columns. The engraving shows the left flank of the British attack as it crumbled and retreated under American fire. British wounded are on the field, and British artillery and can be seen between the infantry and Charlestown. British guns, it was reported after the battle, should have advanced with the infantry but had been supplied with the wrong ammunition and did not advance in support of the infantry until the third assault, after the correct ammunition arrived.

A British Satire on the Plight of British Soldiers

Attributed to James Gillray, artist and engraver

Six-Pence a Day

London: W. Humphrey, October 26, 1775

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

British soldiers led a hard life with little hope of reward, as this satirical print from the first months of the war makes clear. At the center is an emaciated grenadier, his toes poking through his worn-out shoes. His pregnant wife and children are crying out for his help. At his feet is inscribed “The Target,” and two American soldiers, with “Death or Liberty” on their caps, are firing at him. “Famine” awaits him at far right. The figures at left represent three of the most poorly paid trades in Britain—a chairman, a coachman holding a foaming mug of beer (with the publisher’s initials on it) and a ragged little chimney sweep—all better off than the soldier. Their daily pay is in the legend below: “3 Shillings a Day, 2 Shillings a Day, 1 Shilling a Day” while the soldier earns “Six-Pence a Day.”

This is an etching, made by coating a copper plate with “ground”—an acid-resistant coating, often a wax—and then using a thin, needle-like tool to cut fine lines in the ground to create the image. The plate was then submerged in an acid bath, which removed minute amounts of copper where the ground had been cut, incising the design into the plate. This etching is almost certainly an early work of James Gillray, who became the leading British satirical artist of the 1780s and 1790s.

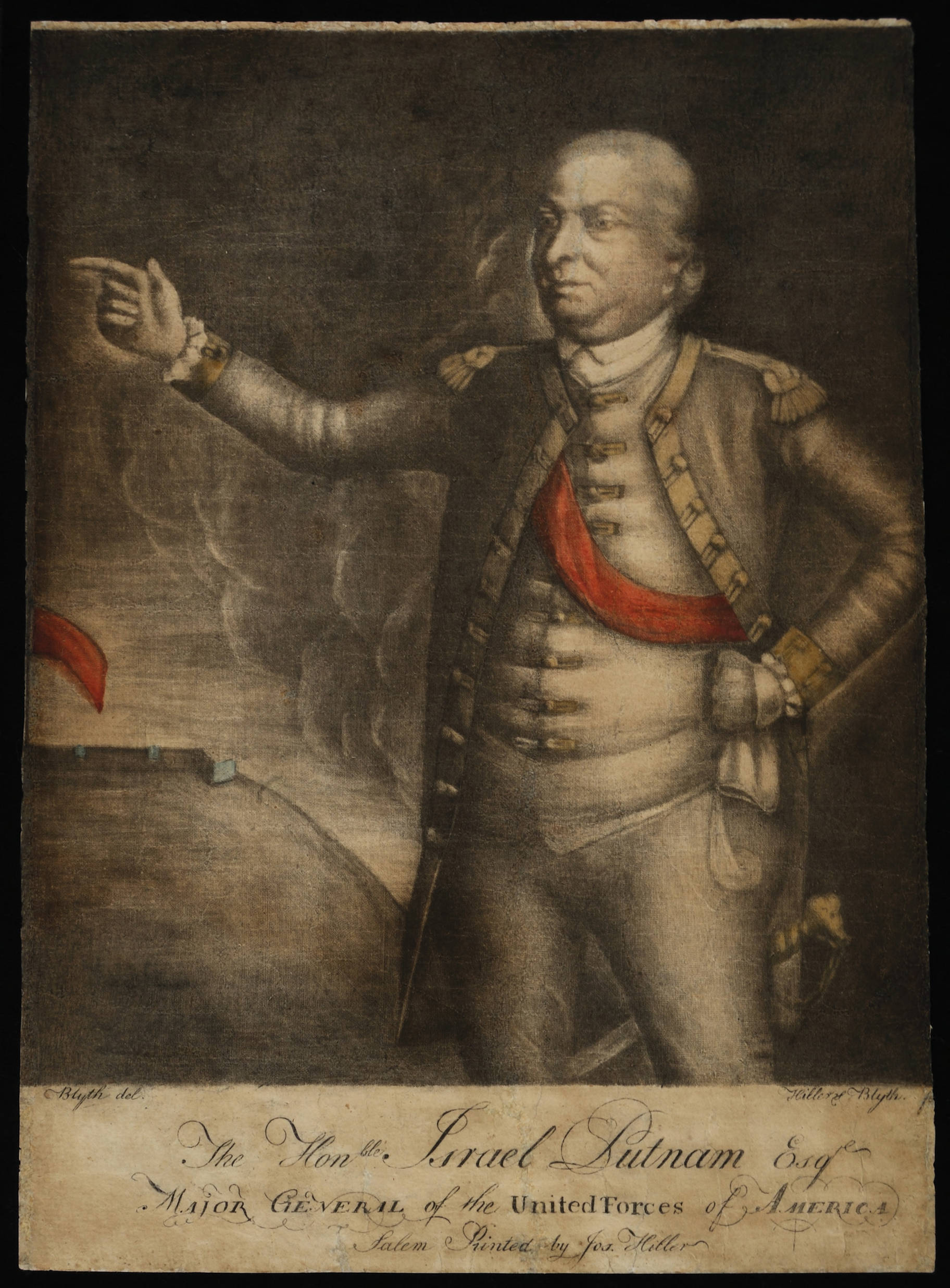

One of the First American Portrait Prints of the War

Benjamin Blyth, artist, and Joseph Hiller, engraver

The Honble Israel Putnam, Esqr, Major General of the United Forces of America

Salem, Mass.: Printed by Joseph Hiller, [1775]

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

This print reflects the market for images of American leaders at the beginning of the Revolutionary War and the efforts of American printmakers to supply that market with prints comparable to the engraved portraits of British officers published and sold by British printmakers. This print of Israel Putnam was probably the first, or one of the first, in the group, and was most likely engraved in the summer or early fall of 1775. Putnam was then widely regarded as the hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill, to which this print alludes. Although Putnam lived most of his life in Connecticut, he had been born near Salem, and the Putnams were still among the town’s most prominent families. Hiller’s engravings are now among the rarest Revolutionary War prints.

The print was based on a portrait by Benjamin Blyth of Salem, Massachusetts—a self-taught artist who worked primarily in pastels, or “crayons” as they were commonly called. His best known works are portraits of John and Abigail Adams, which he executed in 1766 (now among the treasures of the Massachusetts Historical Society). Blyth placed a notice in the Essex Gazette for January 10-17, 1769, advertising his services: “Benjamin Blyth Begs Leave to inform the Public, that he has opened a Room for the Performance of Limning in Crayons, at the House occupied by his Father, in the great Street leading towards Marblehead, where Specimens of his Performance may be seen. All Persons who please to favour him with their Employ, may depend upon having good Likenesses, and being immediately waited on, by applying to their Humble Servant, Benjamin Blyth.”

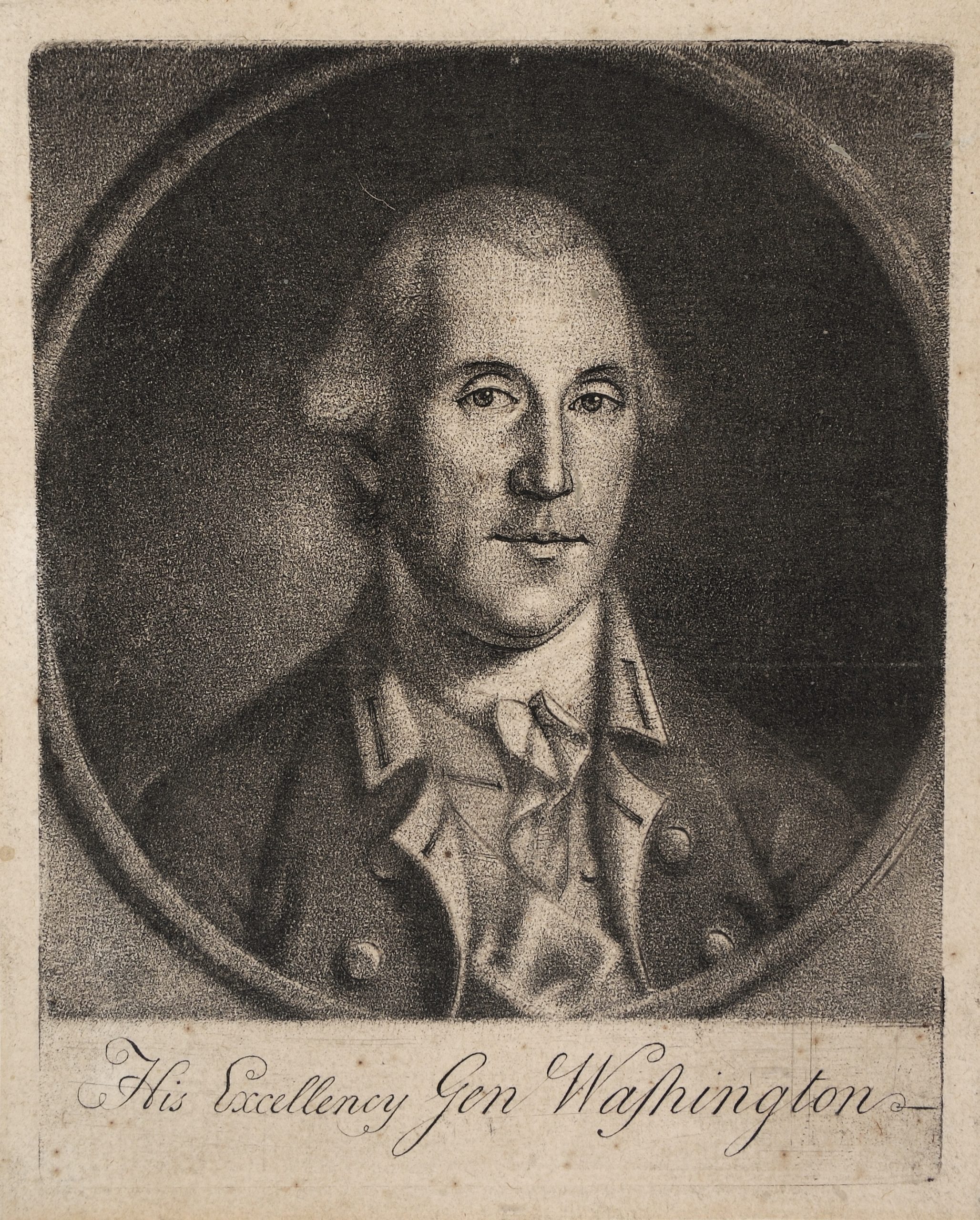

The First Authentic published portrait of George Washington

Charles Willson Peale, artist and engraver

His Excellency Gen Washington

Philadelphia: [Charles Willson Peale], 1778

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Artists and engravers produced imaginary portraits of George Washington from the moment he was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. Charles Willson Peale used his own painted portraits—by 1778 he had painted two three-quarter-length portraits and a portrait miniature of Washington—as the basis for the first authentic published portrait of the general. It bears a closer resemblance to the portrait miniature Peale painted for Martha Washington in 1776 than to the others. Peale taught himself the engraver’s art to produce this small print—a mezzotint Peale embellished with etching. Peale was apparently not happy with his handiwork and probably produced no more than about 150 impressions from the plate.

Mezzotints are a sophisticated form of intaglio engraving produced by preparing a copper plate by scoring it with a rocker and then selectively burnishing the plate to vary the density of the grooves, creating subtle differences that produce tones of varying intensity. A common technique used in Europe to produce printed portraits, the mezzotint process took many years of practice under the guidance of an instructor to master. Only three copies are known today—the Institute’s copy, one in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and one in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. The latter is undoubtedly one of four dozen copies acquired by Don Juan de Miralles, an unofficial emissary from the governor of Cuba. Miralles died suddenly on April 28, 1780, while visiting Washington at the Continental Army camp in Morristown, New Jersey, leaving his account with Peale unpaid. Other artists and engravers obtained copies of the print (and presumably paid for them) and used it as the basis for their wartime images of Washington, magnifying the influence of this print far beyond the small number who ever saw one of Peale’s impressions.

Learn more about this print in Masterpieces in Detail

A French Allegory celebrating American Independence

Antoine Borel, artist, and Jean Charles Levasseur, engraver

L’Amerique Indépendante

Paris: chez l’Auteur, 1778

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

French printmakers dominated the European print market for most of the eighteenth century, and one look at this sophisticated mezzotint makes the reasons clear. It would be hard to imagine a print with richer or more refined details. Allegorical scenes were a favorite of French printmakers and their audiences. This one, celebrating American independence, depicts America—represented as an Indian woman—kneeling before Libertas, the goddess of liberty, identified by her rod with a pileus, or liberty cap. On the left are Mercury, god of commerce, and Ceres, goddess of agriculture. Minerva, goddess of wisdom and war, is at center with her spear poised. At right an allegory of Courage—typically represented with a club—attacks a crowned figure holding a chain, representing Britain. Neptune, with whom Britain was closely identified, lies in the water, his trident broken. Behind Courage, the allegorical figure Prudentia—a female figure representing prudence and the application of principle—stands beside the robed figure of Benjamin Franklin, who uses a ceremonial rod called a vindicta to free America from slavery.

Franklin declined the artist’s request for permission to dedicate the print to him, and when Borel renewed his request, Franklin declined again: “On reading again the Prospectus and Explanation of your Intended Print, I find the whole Merit of giving Freedom to America, continues to be ascrib’d to me, which, as I told you in our first Conversation, I could by no means approve of, as it would be unjust to the Numbers of wise and brave Men who by their Arms and Counsels have shared in the Enterprize and contributed to its Success, (as far as it has yet succeeded) at the Hazard of their Lives and Fortunes.” Franklin urged Borel to substitute a generic figure of a Roman senator for the proposed image of himself and suggested Borel dedicate the print to the Congress of the United States. Borel dedicated the print as Franklin suggested but made the American statesman the central figure in the allegory as he had planned. The drawing was displayed at the engraver’s shop from June 20 to August 20, 1778. The prints were first offered for sale at the end of the year.

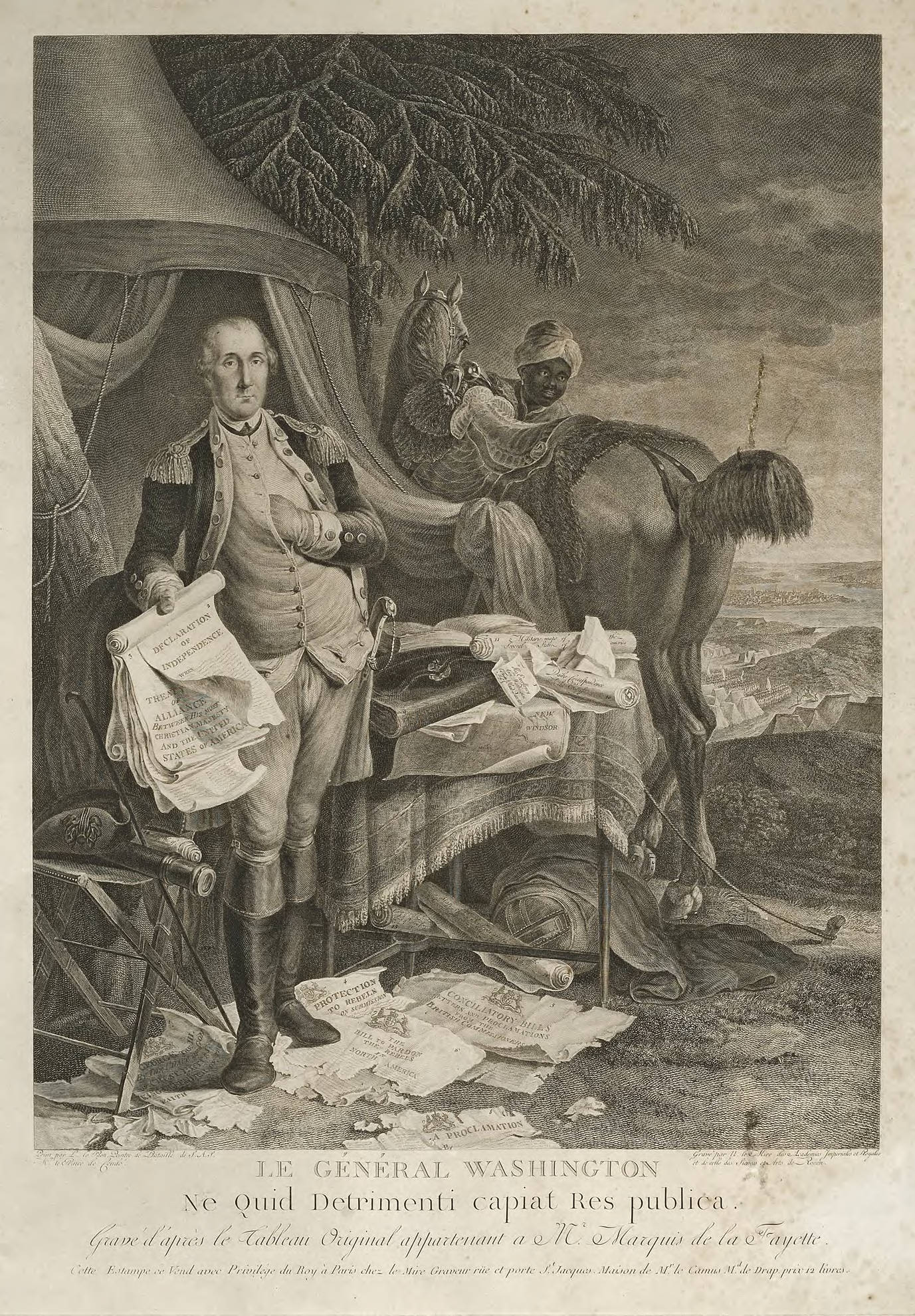

The First Authentic likeness of Washington published in Europe

Jean-Baptiste Le Paon, artist, and Noël Mire, engraver

Le Général Washington, Ne Quid Detrimenti capiat Res Publica

Paris: Chez le Mire, 1780

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

The marquis de Lafayette took a copy of Charles Willson Peale’s 1776 full-length portrait of George Washington with him when he returned to France in 1779 to appeal for the king to send an army to the United States. Jean-Baptiste La Paon painted a portrait of Washington (now owned by Mount Vernon) from the Peale portrait and executed the drawing for this fine mezzotint using the same likeness of Washington. La Paon portrays Washington trampling a variety of British royal proclamations offering pardons and seeking reconciliation while defiantly holding copies of the Declaration of Independence and the Treaty of Alliance with France. On the table are military maps and a portfolio with the title “The Several States and All the Parts of the American Army,” reflecting the broad responsibilities entrusted to the commander-in-chief.

The Latin epigram in the subtitle is a short version of the Roman Senatus consultum ultimum, or final decree of the Senate, to be issued in the event of danger to the republic, authorizing the consuls to appoint a temporary dictator to lead the republic through the crisis. The decree—consules videant ne quid detrimenti capiat res publica—means “the consuls should see to it that the state receive no harm.” The epigram was plainly intended as a tribute to Washington’s conduct in deferring to Congress, even when Congress had vested him with extensive powers. “Instead of thinking myself free’d from all civil Obligations by this mark of their Confidence,” Washington wrote to Congress on January 1, 1777, “I shall constantly bear in Mind, that as the Sword was the last Resort for the preservation of our Liberties, so it ought to be the first thing laid aside, when those Liberties are firmly established.”

The Finest wartime print of an american warship in battle

Richard Paton, artist, and James Fittler and Daniel Lerpinière, engravers

The Memorable Engagement of Captn. Pearson of the Serapis, with Paul Jones of the Bon Homme Richard & his Squadron, Sep. 23 1779

London: John Boydell, 1781

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Far more Britons served in the Royal Navy than in the army, and naval affairs loomed large in the popular consciousness, feeding a large and steady market in Britain for printed portraits of naval officers, depictions of ships and scenes of war at sea. Reproductive prints of painted portraits of admirals and captains sold well, as did battle scenes, often based on paintings commissioned by victorious officers or their patrons. This engraving of the savage night battle between HMS Serapis (at lower left), commanded by Richard Pearson, and Bonhomme Richard, commanded by John Paul Jones, is one of the only wartime prints to depict a warship of the Continental Navy in action—and by far the finest. The engravers, James Fittler and Daniel Lerpinière, based the print on a painting by Richard Paton, one of the most accomplished marine artists of the eighteenth century.

The image depicts the climactic phase in the Battle of Flamborough Head off the coast of Yorkshire, in which the two warships were grappled and Alliance, a frigate attached to Jones’ squadron, fired a broadside into the bow of Bonhomme Richard and the stern of Serapis, causing considerable damage to both vessels. Although Pearson surrendered shortly thereafter, he was praised for saving the valuable fleet of merchant ships he was escorting from the Baltic, which is seen sailing to safety in the right distance. The print was published and marketed by John Boydell, who was largely responsible for developing the print market in Britain. Boydell patronized talented engravers and marketed their work, while developing a brisk international trade in prints that freed artists and printmakers from the constraints of royal and aristocratic patronage.

A British allegorY calling for Peace

Robert Edge Pine, artist, and Joseph Strutt, engraver

America

London: R.E. Pine, 1781

The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati

Robert Edge Pine, the son of an engraver, was born in England about 1730 and was well established as a portrait painter in Bath by the beginning of the American war. Sympathetic to the American cause, he painted a large allegorical canvas in 1778 he titled America, which he described as an allegorical scene in which “America, after having suffered the several evils of war, bewailed its unhappy cause, and lamented over the victims of its fury—her ruined towns—destroy’d commerce, &c. &c. On the appearance of Peace, is represented an extacy of gratitude to the Almighty—Heroic Virtue presents Liberty attended by Concord—Industry, followed by Plenty and her Train, form a group expressive of Population; and Ships denote Commerce.” Suffering America weeps at a cenotaph to four American heroes of the war—James Warren, Richard Montgomery, David Wooster and Hugh Mercer—who had fallen in battle. Pine employed Joseph Strutt, an antiquarian and artist who worked as an engraver (Strutt engraved the illustrations for his own books), to engrave a plate of America, which Pine published himself. The print is dedicated “To Those who wish to Sheathe the Desolating Sword of War And to Restore the Blessings of Peace and Amity to a divided People.”

On August 23, 1784, George Washington’s former neighbor, George William Fairfax, wrote to Washington from Bath that he had sent him “a fine press Print, expressive of the great Oppressions and Calamities of America, also of the glorious Revolution with which it pleasd Heaven to terminate the infernal War. Heroic virtue, who heads up the train of help to weeping America was intended to represent your Excellency, and if your likeness could have been procured, it had been a fine portrait of your Person. Mr Pine the ingenious Allegorical designer and executor of that much admired peice lived very near us and did Mrs Fairfax & self the favor, to consult us oft in designing it. Poor Mr Pine is as true a ‘Son of Liberty’ as any Man can be, ever openly declared it, which with the great crime of publishing the Piece, lost him business, and made so many Enemies in this selfish Nation, that he is compelled to go to America to seek bread in his profession, tho he is certainly one of the first Artists in this Isle. Give me leave to assure you Sir, that there is not a Person in England that merits a better reception in America than the unfortunate Gentn whose only fault was his good wishes to our Country.” Pine arrived in America at the end of 1784 and supported himself painting portraits, which occupied most of his time until his death in 1788. Pine exhibited America in Philadelphia and sold copies of the print. The painting was destroyed by fire in 1803.