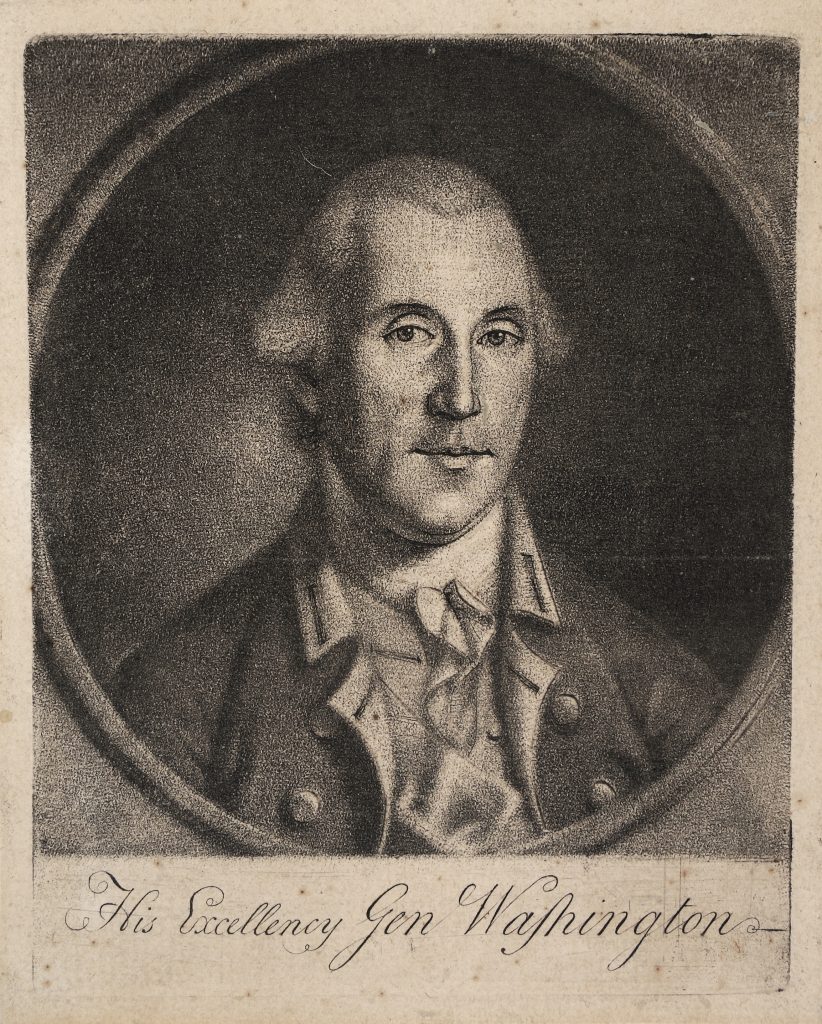

Charles Willson Peale’s mezzotint print of George Washington created in 1778 is one of the rarest and most iconic images of the commander-in-chief of the American forces during the Revolutionary War. It is the first accurate printed likeness of Washington, and the earliest one made by an artist who had painted him from life. Peale’s composition was widely copied by other engravers and became the most recognizable image of Washington during the era of the Revolution. But despite the print’s seminal place in the history of Washington portraiture, the Institute’s copy, acquired for the Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection in 2014, is only one of three examples to be identified in modern times.

Charles Willson Peale’s mezzotint print of George Washington created in 1778 is one of the rarest and most iconic images of the commander-in-chief of the American forces during the Revolutionary War. It is the first accurate printed likeness of Washington, and the earliest one made by an artist who had painted him from life. Peale’s composition was widely copied by other engravers and became the most recognizable image of Washington during the era of the Revolution. But despite the print’s seminal place in the history of Washington portraiture, the Institute’s copy, acquired for the Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection in 2014, is only one of three examples to be identified in modern times.

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) was the preeminent portraitist of the Revolutionary generation. Born in Chester, Maryland, he displayed a prodigious artistic talent from an early age. In 1767, a group of his patrons in Annapolis pooled their money to send him to England, where he studied for three years with the distinguished American-born artist Benjamin West. Returning to Maryland, Peale quickly established himself as one of the most sought-after portrait painters in the middle colonies. In 1772 he became the first artist to paint a portrait of George Washington, the then-retired colonel of the Virginia provincial troops and farmer at Mount Vernon. Peale would paint Washington from life six more times during the years of the Revolutionary War and into the presidency, and the two developed a warm friendship based on mutual respect and admiration.

The existence of the 1778 print of George Washington had long been known to scholars of Peale’s work from the artist’s mentions of it in his diary. On October 16, 1778, he wrote, “Began a Drawing in order to make a Medzo-tinto of Genl. Washington[;] got a Plate of Mr. Brookes and in pay I am to give him 20 of the prints in the first 100 struck.” A month later, on November 16, he noted: “began to print off the small plate of Genl Washington.” Peale produced this print as a mezzotint engraving, an art he had learned a decade earlier while studying in London. His first effort was a mezzotint based on his painted portrait of William Pitt, earl of Chatham, whom he depicted in Roman dress “speaking in Defence of the Claims of the American Colonies.” A form of intaglio printing, a mezzotint (from the Italian mezza tinta or “half-tone”) is characterized by subtle gradations of tone from deep black to white. The 1778 print of George Washington was only Peale’s second experiment with the mezzotint process, but it shows a remarkable mastery of the technically demanding medium.

Unlike the contemporary British engravers who were part of a well-developed printmaking trade, Peale worked on his own, fulfilling the roles of engraver, printer and distributor of the mezzotint. He presented copies of his print of George Washington to several prominent people in Philadelphia, including Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress; Conrad Alexandre Gérard, the new minister from France; David Rittenhouse; and Thomas Paine. Peale’s diary notes that he left prints on consignment (priced at five dollars each) at local shops, including two dozen copies with the printer John Dunlap and a dozen “at Mrs. Mccallisters.” Don Juan de Miralles, a Spanish agent from Cuba, took four dozen prints, though Peale’s accounts note “unpaid” against his entry.

In all, Peale’s records account for about one hundred and fifty strikes from his mezzotint plate. From the moment it was in circulation, the 1778 mezzotint became the principal source of Washington’s image for other artists, including John Norman and Paul Revere. Countless almanacs, broadsides and primers featured portraits of Washington copied from Peale’s distinctive composition, though none captured the finesse of the original.

The apparent popularity of the 1778 image makes the present-day scarcity of the original mezzotint something of a mystery. The noted Peale scholar Charles Coleman Sellers concluded that the small unsigned bust portrait of Washington was ultimately overtaken by Peale’s third venture in the art of mezzotint—a larger and more ambitious composition based on his full-length painting of Washington at Princeton commissioned by the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania in 1779. Peale announced the publication of this new mezzotint in the Pennsylvania Packet on August 26, 1780: “As the first impression of this sort of prints are the most valuable, those who are anxious to possess a likeness of our worthy General are desired to apply immediately.”

While Peale’s 1778 print had been accounted for in a number of catalogues and scholarly studies of George Washington portraiture over the years, no actual print of it was known until the early 1990s, when Wendy Wick Reaves, curator of prints at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, discovered one that had long been held, misattributed, in a private collection and acquired it for the Gallery. Her article “‘His Excellency Genl Washington’: Charles Willson Peale’s Long-Lost Mezzotint Discovered” (American Art Journal 24, no. 1/2 (1992): 44-59) documents her monumental find and demonstrates that Peale’s first mezzotint of Washington was the missing link to a number of printed portraits by other artists who copied it. Another copy of the mezzotint—one sent by Don Juan de Miralles to the governor of Havana—has since been identified in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville.

The 1778 Peale mezzotint, titled His Excellency Genl Washington, was the first authentic likeness of George Washington to reach a popular audience—civilian, military, American, British and European—eager to see the face of the commander-in-chief of the Continental forces fighting for American independence. Peale, though relatively new to the mezzotint process, imbued his image of Washington with great humanity. Based on Washington’s sittings for Peale in 1776 and 1777, it shows Washington in his mid-forties before the greatest stresses and privations of the war had taken their toll on his appearance. The composition most closely resembles the portrait miniature of the general Peale completed for Martha Washington in August 1776 (collection of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

Peale captured the essence of Washington in his role as commander-in-chief that so many contemporaries described in prose. Abigail Adams, who first saw Washington at camp in Cambridge in 1775, wrote to her husband that she was “struck” by his appearance: “Dignity with ease, complacency, the Gentleman and Soldier look agreeably blended in him.” In April 1778, Lt. Samuel Shaw of the Massachusetts Line wrote to a friend in Boston that Washington’s “fortitude, patience, and equanimity of soul, under the discouragements he has been obliged to encounter, ought to endear him to his country, [as] it has done it exceedingly to the army.” Continental Army surgeon James Thatcher also observed Washington in 1778, writing, “The serenity of his countenance, and majestic gracefulness of his deportment impart a strong impression of that dignity and grandeur which are his peculiar characteristics, and no one can stand in his presence without … associating with his countenance the idea of wisdom, philanthropy, magnanimity, and patriotism.”

The French officers were equally impressed with Washington’s appearance and character. Robert-Guilluame Dillon, mestre de camp of Lauzun’s Legion during the Revolutionary War, recorded in his journal numerous encounters with General Washington, of whom he wrote: “[Nature] lui a donné un ensemble qui séduit à mesure qu’on le regarde, son grand caractère et son âme se peignent dans ses traits; j’eus reconnu sans peine le Général entre mille officiers de son armée, c’est un des plus beaux hommes que j’ai vu de ma vie.” [“[Nature] gave him a form which beguiles as one looks at it, his great character and his soul are apparent in his features; I recognized without difficulty the General out of a thousand officers of his army, he was one of the most handsome men that I’ve seen in my life.”]

The marquis de Chastellux, the French officer who served as the liaison between Rochambeau and Washington, summed up his impression of the American commander-in-chief in his wartime travelogue, Voyages de M. le Marquis de Chastellux dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, an English translation of which was published in London in 1787: “The strongest characteristic of this respectable man is the perfect union which reigns between the physical and moral qualities which compose the individual, one alone will enable you to judge all the rest.”

The impact of Charles Willson Peale’s artistry is as immediate and powerful to today’s viewer as it was when the mezzotint was first circulated to his contemporaries. His face of Washington is that of the dignified, confident and compassionate leader of the American Revolution whose character and achievements have inspired every generation since.

See the mezzotint in the Institute’s Digital Library.

Read about a mysterious Spanish version of this print in the blog post El General Washington.

Watch a lecture on early American prints of George Washington by Wendy Wick Reaves, curator emerita of prints and drawings at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

View More Prints in the Institute's Collections