Paintings of scenes from the American Revolution completed between 1790 and 1860 played a critical role in shaping popular understanding of the Revolution. The most important of these paintings, like Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, continue to shape the way Americans think about the Revolution.

Choosing just ten great paintings of the American Revolution from this period is a challenge. John Trumbull painted eight iconic scenes of the American Revolution, in addition to dozens of portraits of participants. Some of the others on our list painted several important paintings of the American Revolution. To illustrate the variety of artists involved and wide range of subjects that drew their interest, we have limited our selections to one great painting by each artist. This means that our list doesn’t include Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence or his Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown—unquestionably two of the most important paintings of the American Revolution. This list is no more than an introduction to a rich and varied group of important works, all of which depict major events.

The impulse to memorialize the American Revolution on canvas was shaped by early published histories of the American Revolution. John Trumbull participated in the American Revolution and knew many of its leading actors, but younger artists increasingly looked to histories and biographies for inspiration. They were also inspired by a growing awareness that the Revolution was passing out of living memory. When Emanuel Leutze exhibited Washington Crossing the Delaware in the fall of 1851, no more than three thousand Revolutionary War veterans were still living. By 1860 that number had fallen to a few dozen.

Several of the works on our list were painted in the 1840s and 1850s, a period of intense efforts by American artists in fostering popular interest in fine art. Artists formed associations to encourage one another, share news, ideas, and information, mount exhibitions, and issue fine prints of recent works, sold to subscribers or members of their organizations. They even commissioned works, like P.F. Rothermel’s stirring painting of Patrick Henry, to be engraved for their members. The mid-century art unions nurtured and sustained fellowship among American artists, creating a kind of artistic community that had never existed in America. Thomas Sully, Asher Durand, P.F. Rothermel, Emanuel Leutze, William Ranney, Christian Schussele, and Alonzo Chappel were all active in these associations.

Some of the works on our list were painted on a grand scale, comparable to the large canvases produced for European palaces and the great houses of European aristocrats. Yet the large historical paintings of Trumbull, Sully, and Leutze were created for popular audiences. When he put Washington Crossing the Delaware on public exhibition, Leutze said, “I want to know what the ‘boys’ will say of it.” Leutze and his contemporaries, regardless of the scale of their paintings, sought to create works expressing the ideals of a democratic republic by celebrating the heroism of ordinary people and the virtues of republican citizens.

None of these works was intended to be a literal depiction of its subject. All of the artists represented here worked hard to portray the people in their paintings correctly. Trumbull drew and painted scores of portraits from life in order to fill his canvases with authentic likenesses, and later artists based their works on contemporary portraits. But their efforts to ensure the literal accuracy of their paintings often extended no further. Most of these paintings are richly and deliberately symbolic, and were conceived to express ideas about the American Revolution rather than reproduce what a contemporary spectator might have seen. Modern critics who point out that Washington crossed the Delaware in a much larger flat-bottomed boat, that the flag at the center of the composition had not been designed yet, or that a practical man like Washington was unlikely to have stood up while being rowed across an ice-choked river in a small boat at night, mistake Leutze’s intent, which was to turn the crossing of the Delaware into a metaphor for American national identity by depicting a diverse group of Americans working to overcome extraordinary challenges and reach a far, indefinite shore together.

Most of the paintings here were reproduced as fine engravings. Some were painted for that purpose. The The late 1840s and 1850s was a high point in the production of fine prints from copper plates in the United States. Nearly all of these paintings were also reproduced in books—from the 1850s these were mainly steel engravings. Many were distributed in inexpensive, derivative prints—often lithographs produced by Kurz and Allison, Currier and Ives, and their competitors. Some were featured on paper money or on toys and games. Reproductions made these images familiar to a vast number of Americans. Familiarity with several of them became an essential aspect of American cultural literacy and remained so through the twentieth century.

The Artist’s personal favorite

John Trumbull

The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton

ca. 1786-1831

Yale University Art Gallery

Inspired by the history paintings of his mentor, Benjamin West, John Trumbull (1756-1843) created a series of eight major historical paintings of the American Revolution. Three memorialize martyred heroes, depicting the deaths of Joseph Warren at Bunker Hill, Richard Montgomery at Quebec, and James Mercer at Princeton. Three celebrate great victories, depicting the surrenders at Trenton, Saratoga, and Yorktown. Two of the paintings depict great moments in the political history of the American Revolution: the presentation of the Declaration of Independence and George Washington resigning his commission. Trumbull began work on this project in the 1780s and it consumed much of his life. He completed scores of portrait studies and painted multiple versions of each work, including four canvases, eighteen by twelve feet each—of the presentation of the Declaration, the surrenders at Saratoga and Yorktown, and Washington’s resignation—which have been on display in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol since 1826.

The four paintings of the American Revolution by Trumbull Congress chose for the Capitol did not include the painting in the series of which Trumbull was proudest: The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton. A complex masterpiece, The Death of Mercer compresses time and space, depicting several episodes in the forty-five minute battle as if they took place at the same moment and in the same place. At left, the British have overrun the leading elements of the Continental Army and a British grenadier is killing Capt. Daniel Neal of the East New Jersey Artillery, which occurred in the opening minutes of the battle. In the center foreground, Trumbull depicted two British soldiers attacking Brig. Gen. James Mercer, who died shortly after the battle. Mercer was mortally wounded several minutes after Neal’s death and more than a hundred yards away. Trumbull used the general’s son, Hugh Mercer, Jr., as the model for his father. To the right, Capt. William Leslie of the 17th Regiment of Foot has been mortally wounded, an event that took place in the opening moments of the battle. Dr. Benjamin Rush, seen riding on to the battlefield behind Washington, was friends with Leslie’s family and saw that he was buried with honor. In the center, Washington has arrived on the battlefield and with a gesture of his sword is directing the counterattack that swept the British from the field—the event that ended the battle. Trumbull conceived the work in the 1780s and worked on versions of it for decades.

See an online lesson about this painting

The First Painting of the crossing of the Delaware

Thomas Sully

The Passage of the Delaware

1819

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In 1817 the state of North Carolina commissioned Thomas Sully (1783-1872) to paint a heroic portrait of George Washington in action for the Senate Hall in the North Carolina State House. Inspired by the description of the crossing in the memoirs of Gen. James Wilkinson, published in 1816, Sully decided to depict the nighttime crossing before the Battle of Trenton. He placed Washington in the center of the action, sitting calmly on his horse while all around him are excited, anxious men. The setting is scrupulously detailed. Sully visited the site in a snowstorm to get it right. McConkey’s ferry house is barely visible on the opposite shore on the left. The men are crossing on flat-bottomed Durham boats, used on the Delaware to move iron. These were precisely the boats the army collected to make the crossing. The night was illuminated by a full moon, which in Sully’s depiction of the scene plays on Washington’s face. In the darkness to his left (our right), Henry Knox, managing the crossing, points with his saber. The mounted black figure is Washington’s servant Billy Lee. Sully identified the figure mounting a horse as Nathanael Greene, and said very specifically that the mounted figure at far right does not represent any particular person.

As Sully’s ambitions for the painting grew, so did its dimensions. The final canvas was seventeen feet by twelve feet—too large for the North Carolina Senate Hall. He offered to paint a smaller version, but the legislature withdrew from the contract. Sully had bigger aspirations. He finished the painting in December 1819 and sent it on a tour to secure the popular acclaim that he hoped would prompt Congress to acquire it for the Capitol Rotunda. The tour began in Norfolk, Virginia, and made its way up the coast to Boston.

Popular interest was tepid. Sully abandoned hope that Congress would buy the painting and sold it for $500 to John Doggett, a Boston frame maker who displayed it in “Doggett’s Repository.” Doggett sold the painting to the proprietor of the New England Museum in Boston, where it was displayed along with other paintings, various wax figures, and an array of natural history specimens. Greenwood sold it to the Boston Museum, a hall of curiosities housed in a theater that included copies of Old Masters, wax figures of Christ and the Apostles, pirates, and Siamese twins, natural history specimens, mummies, and portraits “of the great and good of all nations.” Sully was bitterly disappointed. His friend William Dunlap wrote that for years afterwards, “when the painter hears this picture mentioned, he sometimes says, ‘I wish it were burnt.’” The painting passed to the Museum of Fine Arts in 1903, and in 2019—two hundred years after it was completed, The Passage of the Delaware is finally on public display in the kind of impressive setting Sully imagined.

View a photo essay on the installation of the painting

The Painting that helped enshrine Francis Marion as a Popular hero

John Blake White

General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share His Meal

1836

United States Senate

Francis Marion was immortalized in a popular biography by Mason Locke Weems, first published in 1805. Like Weems’ Life of George Washington—the source of the story of Washington and cherry tree—Weems’ Life of Francis Marion went through dozens of editions and was one of the most popular American books of the early nineteenth century. The most famous anecdote in book describes the visit of a British officer to Marion’s camp to negotiate a prisoner exchange. According to Weems, Marion offered to share his simple dinner of roasted sweet potatoes and water with his guest. The British officer was surprised that Marion lived so simply. “Why, sir,” Marion replied, “the heart is all; and when that is once interested, a man can do any thing. . . . I am in love; and my sweetheart is LIBERTY.” When he returned to his own camp, the officer told his commander: “I have seen an American general and his officers, without pay, and almost without clothes, living on roots, and drinking water—and all for LIBERTY! What chance have we against such men!”

John Blake White (1781-1859), a native of South Carolina, painted this scene at least four times. Versions are now owned by the U.S. Senate and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Secondary sources assign the painting to various dates beginning as early as 1810, but contemporary documentation demonstrates that White finished it in 1836. The painting was first exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1837. A fine mezzotint version by John Sartain was published by the Apollo Association for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in 1840, and thereafter the scene was duplicated in popular prints and inexpensive books, making it one of the most familiar images of the Revolutionary War in the middle years of the nineteenth century. According to the artist’s son, Octavius A. White: “the figure of Marion is a portrait from memory, as my father, when a boy, knew him well. Marion’s farm adjoined the plantation of my grandfather.” White completed three other paintings of the American Revolution in South Carolina, including Sergeants Jasper and Newton Rescuing American Prisoners from the British, Mrs. Motte Directing Generals Marion and Lee to Burn Her Mansion to Dislodge the British, and The Defense of Fort Moultrie.

View the John Sartain engraving of the painting

A French commemoration of the war’s climactic victory

Louise-Charles-Auguste Couder

Siège de Yorktown

1836

Chateau de Versailles

The government of Louis XVI employed artists to commemorate the French role in the American War of Independence, but the revolutionary regime that followed had no interest in celebrating a victory won by aristocratic officers, most of whom were committed royalists. During the reign of Napoleon, French artists focused their efforts on celebrating the emperor’s achievements, and the restored Bourbon monarchy that followed avoided associating France with the American republic. As a consequence, the American Revolution disappeared from government sponsored paintings in France for some forty years.

This changed following the July Revolution of 1830. The new monarch, Louis-Philippe, embraced the role of “citizen-king” and introduced wide-ranging liberal reforms. Louis-Philippe associated his government with the republican idealism of the United States. To distance his government from his autocratic predecessors, Louis-Philippe opened the palace of Versailles to the public as a national museum. A central feature of the new museum was the Gallery of Great Battles, the largest room in the palace, constructed to exhibit forty-four massive paintings, each depicting a major battles in French history—including the climactic victory of the American Revolution.

The French government commissioned Auguste Couder (1789-1873) to depict the French-American victory at Yorktown for the gallery in a canvas of heroic size. Reflecting the government’s effort to associate itself with republican ideals, Couder depicted French and American officers working in concert. Rochambeau is at center, pointing to his right, and appears to be speaking to Col. Christian de Deux-Ponts—the French officer in the white uniform at left. To Deux-Pont’s left, with his hat in his hand, is Maj. Gen. Louis Duportail, a French volunteer serving as the senior engineer in the Continental Army. Washington is on Rochambeau’s left, the two men shoulder to shoulder. Behind and between them is the marquis de Saint-Simon, a French general. Lafayette, a French volunteer in American service, is behind Washington’s left. At right, the marquis de Chastellux—who served as liaison between the French and American armies—studies a map. To complete the composition, Couder depicted French and American flags side by side in front of a tent made of pale blue and white fabric, the colors of the Society of the Cincinnati, the international brotherhood to which the officers depicted all belonged.

Learn more about the Gallery of Great Battles

A Tribute to Civic Virtue

Asher Durand

The Capture of Major André

1845

Birmingham Museum of Art

Benedict Arnold is still remembered as the greatest villain of the Revolutionary War. In 1780, Arnold, then a major general in the Continental Army, attempted to surrender West Point to the British in exchange for £20,000—over $1 million in today’s money. Arnold’s treason was uncovered when three militiamen—John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart, and David Williams—stopped British Major John André inside American lines on the road near Tarrytown. The intermediary between the British army and Arnold, André was wearing civilian clothes and carrying documents provided by Arnold showing the British how to take West Point. According to the three men’s account, André tried to talk them into releasing him, but only succeeded in arousing their suspicions. They searched him and found the incriminating documents in his stocking. In exchange for his release, André offered his expensive watch and promised to send them a large sum of money after he reached British lines. Although poor, they refused and turned their prisoner over to the Continental Army. Arnold’s plot was foiled. Arnold escaped capture, but André was tried and hanged as a spy. In recognition of their fidelity, Congress awarded Paulding, Van Wart, and Williams each a silver medal and a pension of $200 a year.

Accounts of André’s capture were widely published in the years after the war. It was the subject of poems, plays, paintings, and prints. Paulding, Van Wart, and Williams were celebrated as common men of incorruptible virtue. Thomas Sully painted a small depiction of the capture in 1812. Other artists followed, including Jacob Eichholtz and Junius Brutus Stearns. Asher Durand (1796-1886) first painted the scene in 1833-1834. That painting is now in the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts. Durand painted this new and larger version in 1845 to serve as the basis for an engraving issued by the American Art-Union. The central figure is John Paulding, a plainly dressed, handsome yeoman refusing André’s bribes. Durand’s depiction of this scene was reproduced scores of times and became as familiar in the second half of the nineteenth century as Trumbull’s depiction of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, owns what appears to be a preliminary sketch for the painting by Durand, with a somewhat different composition.

View the Asher Durand sketch of the scene

View the use of this image in a nineteenth-century toy

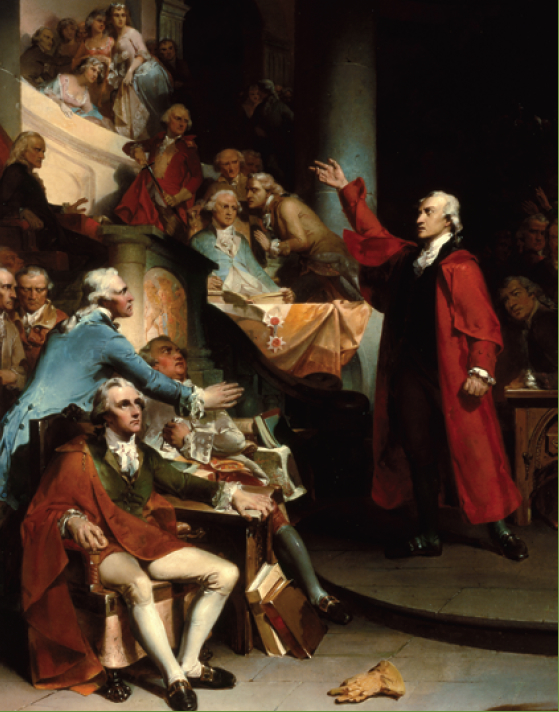

A celebration of the Revolution’s greatest orator

Peter Frederick Rothermel

Patrick Henry Before the House of Burgesses

1851

Red Hill: The Patrick Henry National Memorial

Patrick Henry’s reputation as the greatest orator of the Revolution was firmly established by William Wirt’s Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry, first published in 1817. The text of Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech, which generations of school children recited, was first recorded in Wirt’s biography. Wirt also recorded the conclusion of Henry’s 1765 speech in the Virginia House of Burgesses denouncing the Stamp Act. “It was in the midst of this magnificent debate,” Wirt wrote, “while he was descanting on the tyranny of the obnoxious act, that he exclaimed, in a voice of thunder, and with the look of a god, ‘Cæsar had his Brutus–Charles the first, his Cromwell—and George the third—(‘Treason,’ cried the speaker—’treason, treason,’ echoed from every part of the house. It was one of those trying moments which is decisive of character. Henry faultered not for an instant; but rising to a loftier attitude, and fixing on the speaker an eye of the most determined fire, he finished his sentence with the firmest emphasis) may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it.”

In the spring of 1851, the Philadelphia Art Union, whose leaders included Thomas Sully, Rembrandt Peale, Emanuel Leutze, Christian Schussele, and other artists, commissioned Peter F. Rothermel (1817-1895) to paint a distinguished work in the “national spirit,” which would be engraved and distributed to members of the union in 1852. Rothermel chose the climax of Henry’s Stamp Act speech as the subject for a painting of six by seven feet. The speech took place in the capitol in Williamsburg. Rothermel’s setting is wholly imaginary—the old capitol in Williamsburg had been destroyed by fire in 1832—and designed to give him full play to depict the varied reactions of Henry’s auditors. Richard Henry Lee, who was long allied with Henry in Revolutionary politics, is seated at lower left. Above Lee in the blue jacket, rising to gesture to Henry to stop, is the more conservative Edmund Pendleton. To Lee’s left, Peyton Randolph looks shocked by Henry’s words. In the speaker’s chair in the left background, John Robinson is raising his hands to stop Henry, while other respond with surprise or anger. Rothermel undoubtedly followed Thomas Sully’s posthumous portrait of Henry, even adopting the dramatic red cloak depicted in that portrait, which Thomas Sully adopted from a portrait miniature of Henry painted from life by his brother, Lawrence Sully. To make the importance of the moment clear, a gauntlet lies on the floor in the right foreground, symbolizing Henry’s challenge to British tyranny.

View the key to the people in the painting

The first general across the river

William Tylee Ranney

Marion Crossing the Peede

1851

Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Francis Marion’s popularity as Revolutionary War hero, well-established by Weems, was enhanced by William Cullen Bryant’s poem “The Song of Marion’s Men,” published in 1831. Bryant imagined Marion as a modern Robin Hood, leading a band of merry men in the woodlands and swampy rivers of lowland South Carolina:

Our band is few, but true and tried,

Our leader frank and bold;

The British soldier trembles

When Marion’s name is told.

Our fortress is the good greenwood,

Our tent the cypress tree;

We know the forest round us,

As seamen know the sea.

Bryant’s vision of Marion and his band seems to have inspired William Tylee Ranney (1813-1857) to depict the “Swamp Fox” surrounded by his men crossing a lowland river. Ranney was born in Connecticut but at thirteen he went to live with an aunt in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he was apprenticed to a tinsmith. His interest in the Revolutionary War in the South was shaped by this experience. He settled in Brooklyn in 1833, but his passion for adventure led him to volunteer for service in the Texas War of Independence in 1836-1837. He lived in and around New York for the rest of his life, devoting most of his career to genre scenes and historical paintings of the American Revolution and the West.

In 1850 the Bulletin of the American Art-Union reported that Ranney “is engaged on a large picture of Marion crossing the Peede, the drawing and composition of which are praised.” Ranney may have been inspired by early reports of Emanuel Leutze’s work on Washington Crossing the Delaware, which was mentioned several time in the Bulletin beginning in October 1849, but he could not have seen the painting or known much about its composition before he completed Marion Crossing the Peede, which the Art-Union exhibited in 1851. At seventy-four by fifty inches, the painting was dwarfed by Washington Crossing the Delaware, which went on exhibition in New York a short time later.

Marion Crossing the Peede (the title mispelled the name of the Pee Dee River) depicts men, horses, and dogs crowded on a flatboat. The casual viewer is likely to assume Francis Marion is the officer mounted on a black horse. Marion is actually the mounted officer wrapped in a brown cloak—the epaulet gives him away. This was a clever visual tribute to Marion’s ability to disguise his plans and hide from his enemies.

The Most Famous Painting of the Revolutionary War

Emanuel Leutze

Washington Crossing the Delaware

1851

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Since it went on display in New York City in the fall of 1851,Washington Crossing the Delaware has been recognized as one of the great paintings of the American Revolution. Its size—twenty-one feet three inches by twelve feet five inches exclusive of the frame—exceeds Trumbull’s largest works, and dwarfed most other American historical paintings of its time. The figures in the painting are all life size.

The artist, Emanuel Leutze (1816-1868) was born in Württemberg, but was brought to America as a child. He lived in Philadelphia, where he learned draftsmanship and the rudiments of painting, until he was twenty-five, when he returned to Düsseldorf to enroll in the Royal Art Academy. Leutze remained in Germany from 1841 to 1851, completed his training and established himself as a history painter. He conceived of Washington Crossing the Delaware after the failure of the Revolution of 1848 in Germany. At first that revolution promised to unify the German states, introduce liberal reforms, and empower representative bodies responsive to the popular will, but it fell victim to class divisions, regional interests, and the stubborn resistance of aristocrats anxious to hold on to their traditional prerogatives. Washington Crossing the Delaware offers a different vision of revolution, in which people from different classes, regions, and ethnic backgrounds work together under a determined, charismatic leader to overcome extraordinary obstacles and reach a common goal.

Modern critics who point out that Washington Crossing the Delaware is inaccurate misunderstand the artist’s intentions and the expectations of his original audience. “The chief object sought in such a work,” an early reviewer wrote, “is to present in the most powerful and intelligible form the ideas and circumstances that make up some momentous historical fact.” The painting is a visual metaphor for the American Revolution, and by extension, for the American national experience.

The central figure in the boat is Washington, “in his features and attitude an expression of dauntless energy,” the same reviewer wrote. Seated to Washington’s left is Nathanael Greene, and behind Washington, young James Monroe holds the flag tight in the face of the cold wind. The other nine figures represent the diversity of the American people brought together in the Revolutionary cause. In the bow, a soldier wears a Scotsman’s cap, and behind him, a black soldier pushes away the floating ice. At the stern, a soldier with black hair, high cheekbones, and a beadwork bag on his hip appears to be an American Indian. None of the enlisted men are in uniform or even dressed alike. The men represent the diverse people of Revolutionary America, working together to reach a shared goal.

A Confident American Confronts his Accusers

Christian Schussele

Franklin Appearing before the Privy Council

ca. 1856

The Huntington Art Museum, Library, and Botanical Garden

Christian Schussele (1824-1879) was born in Alsace and taught himself to paint before studying lithography in Strasbourg. In 1843 he was employed making lithographs of the paintings in the Gallery of Great Battles at Versailles. This work ended abruptly with the Revolution of 1848, and Schuselle—then twenty-four—emigrated to Philadelphia. There he was patronized by John Sartain, the nation’s leading mezzotint engraver, who encouraged Schuselle to paint and engraved his paintings for sale. Schussele painted until 1863, when a palsy in his hand cut short his career as an artist.

Franklin Appearing before the Privy Council was Schussele’s first ambitious historical painting. It depicts the appearance of Benjamin Franklin—then in London as agent of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Massachusetts—to answer questions regarding the conduct of the colonies, especially the destruction of the tea in Boston on December 16, 1773. During the interview, Franklin was personally abused by Alexander Wedderburn, the crown solicitor, to the amusement of the lords and ladies present. Wedderburn mocked Franklin’s reputation as a scientist and accused him of encouraging treason. Franklin listened in silence to Wedderburn’s harangue and then left the hall, declining to be deposed. The episode—symbolizing the alienation of the colonies from Britain—occupied a whole chapter in volume six (1854) of George Bancroft’s History of the United States. The painting was engraved by Robert Whitechurch and published in 1859. The book that accompanied the print explained that the work had been eight years in the making—suggesting that Schussele began the painting in 1851, the year Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware created such a sensation and inspired artists to put their hands to large-scale history painting. The book also presented a key identifying thirty-nine people portrayed in the painting. Schussele exhibited another American Revolution painting—Washington at Valley Forge—in 1859.

The Maryland Line Saves Washington’s Army

Alonzo Chappel

Battle of Long Island

1858

Brooklyn Historical Society

Alonzo Chappel (1828-1887) exhibited talent as a painter before he was ten and earned money painting portraits and theatrical stage scenery while still in his teens. He refined his skills under the instruction of Samuel F.B. Morse, and became one of the most prolific historical painters of his generation. Unlike his older contemporaries, who relied on the sale of fine engravings of their works, Chappel worked mainly as an illustrator, producing paintings reproduced—mainly as steel engravings—in books. Chappel’s paintings include hundreds of portraits and historical paintings, chiefly of subjects from the American Revolution and the Civil War. Few of them survive, at least in public collections, and most are know only through contemporary prints. In the 1850s Chappel was employed by publisher Henry J. Johnson of Johnson, Fry & Company to illustrate historical and biographical works, including Jesse Spencer’s History of the United States, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time, an ambitious series that ultimately filled four volumes, each illustrated with full page steel engravings based on original paintings, many of them by Chappel.

The most powerful of Chappel’s paintings of the American Revolution depicts the climactic moment of the Battle of Long Island. It was commissioned by Johnson, Fry & Company, which published a steel engraving of it in 1858. In it, the Maryland Continental Line, obscured by battle smoke in the middle of the scene, holds off the final British attack while a large part of the Continental Army wades into Denton’s Mill Pond to escape entrapment and make its way to the shelter of Washington’s fortified lines on the heights of Brooklyn. The building at right is a tidal mill on marshy Gowanus Creek, which bordered the battlefield on the west. Chappel chose to depict the chaos and blind panic of the retreat as a way to emphasize the heroic sacrifice of the Maryland troops, who sustained enormous casualties protecting the retreating men. Historian David McCullough regards this one of the great paintings of the American Revolution, commenting that it “gives a sense of what battles really were like.” Having been born and spent most of his life in Brooklyn, Chappel was acquainted with the setting, although the area depicted in the painting was on the edge of the developed part of Brooklyn in the 1850s, and was overtaken by industrial development in the following decade.

View the 1858 engraving of the painting