What did George Washington look like? We know, or think we know, because we have seen dozens of portraits of him. We carry his image in our pockets, on our dollar bills and our loose change. And though the most familiar portraits by Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale and John Trumbull differ somewhat, most of us think we would recognize Washington if we met him in person—unexpected as that would be.

Washington is so famous that it is hard to imagine a time when Americans didn’t know what he looked like. But during the first years of the Revolutionary War, the only people who knew what Washington looked like were people who had seen him in person or had seen one of the very few painted portraits of him.

Printers tried to fill this void with imaginary portraits based on written descriptions—someone who had seen the general said he had a prominent nose, a broad forehead, a firm jaw or simply a “noble countenance”—but these portraits no more resembled Washington than they resembled any other middle-aged man in a general’s uniform.

Charles Willson Peale, the great Philadelphia portrait painter, set out to correct this. Peale had first painted Washington from life in 1772 and had seen and painted the general several times since. On October 16, 1778, Peale wrote in his diary that he “Began a Drawing in order to make a Medzo-tinto of Genl. Washington. got a Plate of Mr. Brookes and in pay I am to give him 20 of the prints in the first 100 struck.”

The plate was a small rectangle of polished copper, perfectly flat, on which Peale engraved his image of Washington. A mezzotint (from the Italian mezza tinta or “half-tone”) is a sophisticated form of intaglio (or inward cut) printing characterized by subtle gradations of tone from deep black to white produced with nothing more than black ink on paper. The shading is produced by varying the depth of the image by burnishing areas of the heavily roughened surface of the copper plate, which in turn varies the amount of ink conveyed to the paper.

Peale recorded on November 16 that he “began to print off the small plate of Genl Washington.” He presented copies of the print to several prominent people in Philadelphia, including Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress; Conrad Alexandre Gérard, the new minister from France; David Rittenhouse, a clockmaker and self-taught scientist; and Thomas Paine, the famous author of Common Sense. Peale left prints on consignment, priced at five dollars each, at local shops, including two dozen copies left with printer John Dunlap and a dozen “at Mrs. Mccallisters.”

Peale’s composition was copied by other engravers and became the most widely disseminated image of Washington during the Revolutionary War. Through the war years, this was the face of George Washington to Americans who never saw the great man in person. Yet today Peale’s original print is exceedingly rare. Only three are known. One in exceptionally fine condition is among the treasures of our own Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection. The other two are now in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington and the General Archives of the Indies in Seville, Spain.

In all, Peale’s records account for about one hundred and fifty strikes from his mezzotint plate. Why then, is it so rare?

The main reason appears to be that four dozen copies—nearly a third of Peale’s print run—were taken by Don Juan de Miralles, a Spanish agent who admired Washington. This would account for the survival of a copy in the Archives of the Indies in Seville. Miralles probably sent some, or perhaps nearly all, of the forty-eight copies to Spain before his untimely death in 1780. Ironically, Peale did not benefit from this large sale. In his accounts, Peale noted “unpaid” against Miralles’ entry.

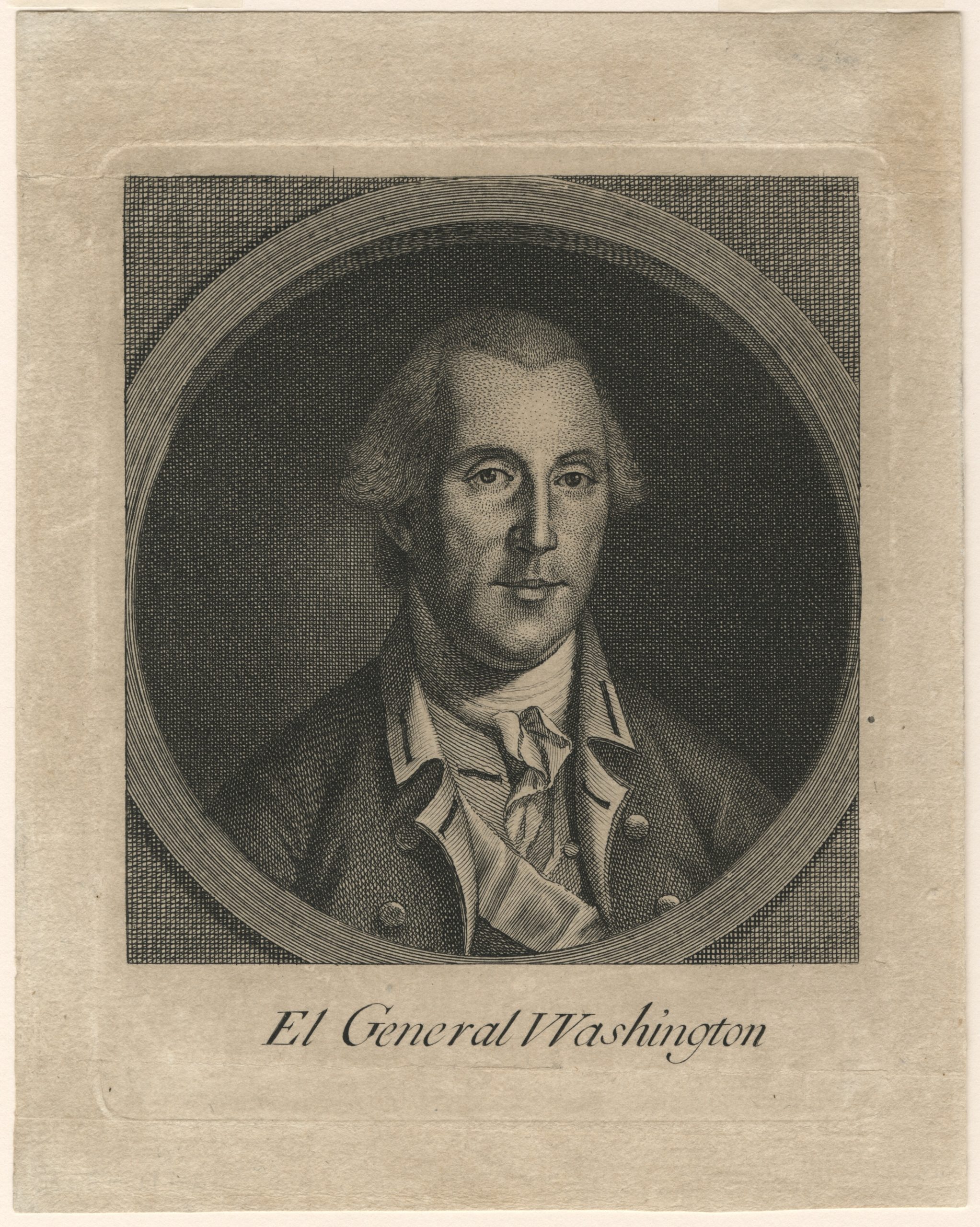

Rare as it is, there may be a version of it that’s rarer still. Among the most recent additions to our library collections is a little print, obviously derived from the 1778 Peale mezzotint, bearing the simple legend El General Washington (the “W” in Washington printed as a double-V). This extraordinary little print does not include the name of the publisher or the engraver or even supply a date. It is an enigma.

Unlike Peale’s mezzotint, this portrait was created as a line engraving (where the design is cut into a smooth plate and shading is created by hatching, cross-hatching and dots)—but who engraved it and when? No one seems to have figured this out.

Unlike Peale’s mezzotint, this portrait was created as a line engraving (where the design is cut into a smooth plate and shading is created by hatching, cross-hatching and dots)—but who engraved it and when? No one seems to have figured this out.

El General Washington is not listed in WorldCat, a collective catalog of the world’s libraries—the largest catalog of printed materials in the world. Nor is it listed separately in the online digital catalogs of the world’s leading research libraries. The print does not appear in the catalog of the Biblioteca Nacional de Espana, the Spanish analog of the Library of Congress; the British Library; and the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Nor is it found in the extraordinary collection of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando—the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando—in Madrid, which serves as the home of the Calcografía Nacional, the world’s greatest collection of Spanish copperplate engravings. Founded by the Spanish Crown in 1789, the Calcografía Nacional gathered up an impressive number of eighteenth-century engraved plates from private publishers and those working under the patronage of the government. The collection includes some eight thousand plates, but El General Washington does not appear to be among them. A search through the catalogs of Spain’s great art collections—including the Prado, which has an impressive collection of eighteenth-century Spanish prints—yields no clue about the phantom.

Nor is the print mentioned in the important early Spanish works on Spain and the American Revolution by Manuel Serrano y Sanz, Manuel Conrotte and Juan F. Yella Utrilla, though their books were informed by deep study in the Spanish archives where a copy of this fugitive print might be hiding.

And finally—in all the voluminous literature on Washington portraits, we can find only three mentions of El General Washington. The pioneering American print collector and scholar William S. Baker, in his book The Engraved Portraits of Washington, published in 1880, does not illustrate but clearly describes this print: [after Charles Willson Peale] “El General VVashington. Bust in uniform, Head slightly to right. Circle, with border the sides partly reduced, in a square. Line,” adding “only one impression of this has come under the notice of the writer.”

Baker’s work inspired a new generation of collectors and scholars of printed portraits of Washington. One of them, Baker’s protégé Charles Henry Hart, compiled a new and expanded Catalogue of the Engraved Portraits of Washington, which was published by the Grolier Club in 1904. Hart also listed El General Washington: “Bust, full to right, in uniform, with ribband, but without epaulettes. Circle, with border, 5/16 cut off to rectangle. Line.”

That same year, an impression of El General Washington was sold at auction by Stan V. Henkels of Philadelphia as part of a large collection of engraved portraits assembled by Philadelphia lawyer Hampton L. Carson. (Carson is acknowledged in Hart’s catalogue and it is very likely that this is the same engraving Hart—and probably Baker—had seen.) Henkels described the print as “a beautiful impression of one of the rarest and most interesting portraits of Washington,” and included an illustration of it. To add to the complexity of our story, there is another print by a Spanish printmaker, Mariano Brandi, titled El General Washington. That print, which Hart also cataloged, is a Spanish version of the portrait of Washington in profile based on a drawing by Pierre Eugène Du Simitière, and is a completely different work.

The present-day print shop from which we purchased our impression of El General Washington traced the provenance of our print to the family of Zachary Taylor Hollingsworth, another early twentieth-century connoisseur of engraved portraits who was actively collecting “portraits of Washington from all countries, with every degree of merit” at the time of the Carson sale.

Our search for any other references to this fugitive print leaves us wondering: did the Society just acquire the “one impression” Baker first documented more than 140 years ago? Is there another? The print is clearly Spanish—the title gives it away, but so does the open, woven appearance of the corners and the background, which is consistent with many Spanish prints of the late eighteenth century. But the absence of names of engraver and publisher is curious. Spanish engravers included these just as conventionally as their British, French and German counterparts. They sometimes don’t appear in the proofs struck before printing. This is an extraordinarily clear, well-struck print. Could our fugitive be a proof before printing? Or was the plate made, some proofs struck, but copies never struck for sale to the public?

And perhaps the most important question: who in Spain was interested enough in George Washington to want to see a fine portrait of him published? Washington had admirers in Spain including Miralles’ eventual replacement, Diego de Gardoqui. As a partner in the firm of José de Gardoqui e Hijos of Bilbao, he supplied the American army with 215 bronze cannon, 30,000 muskets, 30,000 bayonets, some 500,000 musket balls, 300,000 pounds of powder and other supplies during the war. After the Revolution he became Spain’s envoy to the United States. A cultured gentleman, he presented Washington with a four-volume edition of Don Quixote. He was later succeeded by a member of his staff, José de Jáudenes, who commissioned an Italian artist then living in Philadelphia, Giuseppe Perovani, to paint him a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s magnificent full-length portrait of Washington, which he sent back to Spain. The painting is now in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

Either man, or some other Spaniard with close ties to the United States, might have interested himself in publishing El General Washington—a curious, fugitive reminder of Spain’s involvement in our war for independence.

Ellen McCallister Clark

and Jack D. Warren, Jr.

El General Washington (above) was acquired for the library collections with a gift from a private foundation.